Theropoda, whose members are known as theropods, is a dinosaur clade that is characterized by hollow bones and three toes and claws on each limb. Theropods are generally classed as a group of saurischian dinosaurs. They were ancestrally carnivorous, although a number of theropod groups evolved to become herbivores and omnivores. Theropods first appeared during the Carnian age of the late Triassic period 231.4 million years ago (Ma) and included the majority of large terrestrial carnivores from the Early Jurassic until at least the close of the Cretaceous, about 66 Ma. In the Jurassic, birds evolved from small specialized coelurosaurian theropods, and are today represented by about 10,500 living species.

Gallimimus is a genus of theropod dinosaur that lived in what is now Mongolia during the Late Cretaceous period, about seventy million years ago (mya). Several fossils in various stages of growth were discovered by Polish-Mongolian expeditions in the Gobi Desert of Mongolia during the 1960s; a large skeleton discovered in this region was made the holotype specimen of the new genus and species Gallimimus bullatus in 1972. The generic name means "chicken mimic", referring to the similarities between its neck vertebrae and those of the Galliformes. The specific name is derived from bulla, a golden capsule worn by Roman youth, in reference to a bulbous structure at the base of the skull of Gallimimus. At the time it was named, the fossils of Gallimimus represented the most complete and best preserved ornithomimid material yet discovered, and the genus remains one of the best known members of the group.

Coelurosauria is the clade containing all theropod dinosaurs more closely related to birds than to carnosaurs.

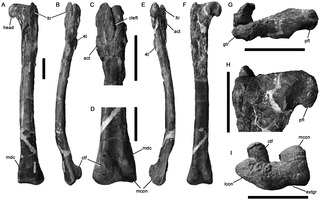

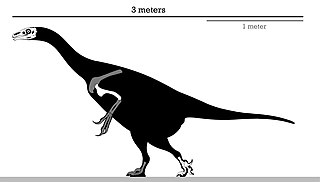

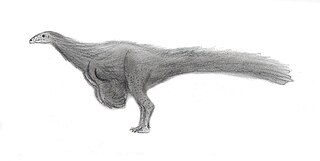

Anserimimus is a genus of ornithomimid theropod dinosaur, from the Late Cretaceous Period of what is now Mongolia. It was a lanky, fast-running animal, possibly an omnivore. From what fossils are known, it probably closely resembled other ornithomimids, except for its more powerful forelimbs.

Ornithomimosauria are theropod dinosaurs which bore a superficial resemblance to the modern-day ostrich. They were fast, omnivorous or herbivorous dinosaurs from the Cretaceous Period of Laurasia, as well as Africa and possibly Australia. The group first appeared in the Early Cretaceous and persisted until the Late Cretaceous. Primitive members of the group include Nqwebasaurus, Pelecanimimus, Shenzhousaurus, Hexing and Deinocheirus, the arms of which reached 2.4 m (8 feet) in length. More advanced species, members of the family Ornithomimidae, include Gallimimus, Struthiomimus, and Ornithomimus. Some paleontologists, like Paul Sereno, consider the enigmatic alvarezsaurids to be close relatives of the ornithomimosaurs and place them together in the superfamily Ornithomimoidea.

Struthiomimus, meaning "ostrich-mimic", is a genus of ornithomimid dinosaurs from the late Cretaceous of North America. Ornithomimids were long-legged, bipedal, ostrich-like dinosaurs with toothless beaks. The type species, Struthiomimus altus, is one of the more common, smaller dinosaurs found in Dinosaur Provincial Park; their overall abundance—in addition to their toothless beak—suggests that these animals were mainly herbivorous or omnivorous, rather than purely carnivorous, if at all. Similar to the modern extant ostriches, emus, and rheas, ornithomimid dinosaurs likely lived as opportunistic omnivores, supplementing a largely plant-based diet with a variety of small mammals, reptiles, amphibians, insects, invertebrates, and anything else they could fit into their mouth, as they foraged.

Ornithomimus is a genus of ornithomimid theropod dinosaurs from the Campanian and Maastrichtian ages of Late Cretaceous Western North America. Ornithomimus was a swift, bipedal dinosaur which fossil evidence indicates was covered in feathers and equipped with a small toothless beak that may indicate an omnivorous diet. It is usually classified into two species: the type species, Ornithomimus velox, and a referred species, Ornithomimus edmontonicus. O. velox was named in 1890 by Othniel Charles Marsh on the basis of a foot and partial hand from the Denver Formation of Colorado. Another seventeen species have been named since then, though almost all of them have been subsequently assigned to new genera or shown to be not directly related to Ornithomimus velox. The best material of species still considered part of the genus has been found in Alberta, representing the species O. edmontonicus, known from several skeletons from the Horseshoe Canyon Formation. Additional species and specimens from other formations are sometimes classified as Ornithomimus, such as Ornithomimus samueli from the earlier Dinosaur Park Formation.

Dromiceiomimus is a genus of ornithomimid theropod from the Late Cretaceous of Alberta, Canada. The type species, D. brevitertius, is considered a synonym of Ornithomimus edmontonicus by some authors, while others consider it a distinct and valid taxon. It was a small ornithomimid that weighed about 135 kilograms (298 lb).

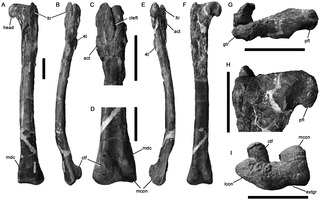

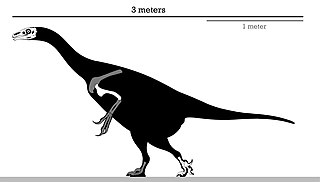

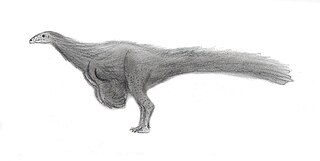

Deinocheirus is a genus of large ornithomimosaur that lived during the Late Cretaceous around 70 million years ago. In 1965, a pair of large arms, shoulder girdles, and a few other bones of a new dinosaur were first discovered in the Nemegt Formation of Mongolia. In 1970, this specimen became the holotype of the only species within the genus, Deinocheirus mirificus; the genus name is Greek for "horrible hand". No further remains were discovered for almost fifty years, and its nature remained a mystery. Two more complete specimens were described in 2014, which shed light on many aspects of the animal. Parts of these new specimens had been looted from Mongolia some years before, but were repatriated in 2014.

Garudimimus is a genus of ornithomimosaur that lived in Asia during the Late Cretaceous. The genus is known from a single specimen found in 1981 by a Soviet-Mongolian paleontological expedition in the Bayan Shireh Formation and formally described in the same year by Rinchen Barsbold; the only species is Garudimimus brevipes. Several interpretations about the anatomical traits of Garudimimus were made in posterior examinations of the specimen, but most of them were criticized during its comprehensive redescription in 2005. Extensive undescribed ornithomimosaur remains at the type locality of Garudimimus may represent additional specimens of the genus.

Archaeornithomimus is a genus of ornithomimosaurian theropod dinosaur that lived in Asia during the Late Cretaceous period, around 96 million years ago in the Iren Dabasu Formation.

Timimus is a genus of small coelurosaurian theropod dinosaur from the Early Cretaceous of Australia. It was originally identified as an ornithomimosaur, but now it is thought to be a different kind of theropod, possibly a tyrannosauroid.

Erlikosaurus is a genus of therizinosaurid that lived in Asia during the Late Cretaceous period. The fossils, a skull and some post-cranial fragments, were found in the Bayan Shireh Formation of Mongolia in 1972, dating to around 96 million and 89 million years ago. These remains were later described by Altangerel Perle and Rinchen Barsbold in 1980, naming the new genus and species Erlikosaurus andrewsi. It represents the second therizinosaur taxon from this formation with the most complete skull among members of this peculiar family of dinosaurs.

Nqwebasaurus is a basal coelurosaur and is the basal-most member of the coelurosaurian clade Ornithomimosauria from the Early Cretaceous of South Africa. The name Nqwebasaurus is derived from the Xhosa word Nqweba which is the local name for the Kirkwood district, and thwazi is ancient Xhosa for "fast runner". Currently it is the oldest coelurosaur in Africa and shows that basal coelurosaurian dinosaurs inhabited Gondwana 50 million years earlier than previously thought. The type specimen of Nqwebasaurus was discovered by William J. de Klerk who is affiliated with the Albany Museum in Grahamstown. It is the only fossil of its species found to date and was found in the Kirkwood Formation of the Uitenhage Group. Nqwebasaurus has the unofficial nickname "Kirky", due to being found in the Kirkwood.

Deinocheiridae is a family of ornithomimosaurian dinosaurs, living in Asia and the Americas from the Albian until the Maastrichtian. The family was originally named by Halszka Osmólska and Roniewicz in 1970, including only the type genus Deinocheirus. In a 2014 study by Yuong-Nam Lee and colleagues and published in the journal Nature, it was found that Deinocheiridae was a valid family. Lee et al. found that based on a new phylogenetic analysis including the recently discovered complete skeletons of Deinocheirus, the type genus, as well as Garudimimus and Beishanlong, could be placed as a successive group, with Beishanlong as the most primitive and Deinocheirus as most derived. The family Garudimimidae, named in 1981 by Rinchen Barsbold, is now a junior synonym of Deinocheiridae as the latter family includes the type genus of the former. The group existed from 115 to 69 million years ago, with Beishanlong living from 115 to 100 mya, Garudimimus living from 98 to 83 mya, and Deinocheirus living from 71 to 69 mya. Other genera included are Paraxenisaurus, and possibly Harpymimus and Hexing.

Maniraptoriformes is a clade of dinosaurs with pennaceous feathers and wings that contains ornithomimosaurs and maniraptorans. This group was named by Thomas Holtz, who defined it as "the most recent common ancestor of Ornithomimus and birds, and all descendants of that common ancestor."

This timeline of oviraptorosaur research is a chronological listing of events in the history of paleontology focused on the oviraptorosaurs, a group of beaked, bird-like theropod dinosaurs. The early history of oviraptorosaur paleontology is characterized by taxonomic confusion due to the unusual characteristics of these dinosaurs. When initially described in 1924 Oviraptor itself was thought to be a member of the Ornithomimidae, popularly known as the "ostrich" dinosaurs, because both taxa share toothless beaks. Early caenagnathid oviraptorosaur discoveries like Caenagnathus itself were also incorrectly classified at the time, having been misidentified as birds.

This timeline of ornithomimosaur research is a chronological listing of events in the history of paleontology focused on the ornithomimosaurs, a group of bird-like theropods popularly known as the ostrich dinosaurs. Although fragmentary, probable, ornithomimosaur fossils had been described as far back as the 1860s, the first ornithomimosaur to be recognized as belonging to a new family distinct from other theropods was Ornithomimus velox, described by Othniel Charles Marsh in 1890. Thus the ornithomimid ornithomimosaurs were one of the first major Mesozoic theropod groups to be recognized in the fossil record. The description of a second ornithomimosaur genus did not happen until nearly 30 years later, when Henry Fairfield Osborn described Struthiomimus in 1917. Later in the 20th century, significant ornithomimosaur discoveries began occurring in Asia. The first was a bonebed of "Ornithomimus" asiaticus found at Iren Debasu. More Asian discoveries took place even later in the 20th century, including the disembodied arms of Deinocheirus mirificus and the new genus Gallimimus bullatus. The formal naming of the Ornithomimosauria itself was performed by Rinchen Barsbold in 1976.

Rativates is a genus of ornithomimid theropod dinosaur from the Dinosaur Park Formation of Alberta. The type species is Rativates evadens.

Aepyornithomimus is a genus of ornithomimid theropod dinosaur from the Late Cretaceous Djadokhta Formation in Mongolia. It lived in the Campanian, around 75 million years ago, when the area is thought to have been a desert. The type and only species is A. tugrikinensis.