In music theory, the term mode or modus is used in a number of distinct senses, depending on context.

The major scale is one of the most commonly used musical scales, especially in Western music. It is one of the diatonic scales. Like many musical scales, it is made up of seven notes: the eighth duplicates the first at double its frequency so that it is called a higher octave of the same note.

In music theory, the minor scale has three scale patterns – the natural minor scale, the harmonic minor scale, and the melodic minor scale – mirroring the major scale, with its harmonic and melodic forms.

In music, harmony is the concept of combining different sounds together in order to create new, distinct musical ideas. Theories of harmony seek to describe or explain the effects created by distinct pitches or tones coinciding with one another; harmonic objects such as chords, textures and tonalities are identified, defined, and categorized in the development of these theories. Harmony is broadly understood to involve both a "vertical" dimension (frequency-space) and a "horizontal" dimension (time-space), and often overlaps with related musical concepts such as melody, timbre, and form.

In music theory, a scale is any set of musical notes ordered by fundamental frequency or pitch. A scale ordered by increasing pitch is an ascending scale, and a scale ordered by decreasing pitch is a descending scale.

In music, the tonic is the first scale degree of the diatonic scale and the tonal center or final resolution tone that is commonly used in the final cadence in tonal classical music, popular music, and traditional music. In the movable do solfège system, the tonic note is sung as do. More generally, the tonic is the note upon which all other notes of a piece are hierarchically referenced. Scales are named after their tonics: for instance, the tonic of the C major scale is the note C.

In music theory, the key of a piece is the group of pitches, or scale, that forms the basis of a musical composition in Western classical music, art music, and pop music.

Tonality or key: Music which uses the notes of a particular scale is said to be "in the key of" that scale or in the tonality of that scale.

In a musical composition, a chord progression or harmonic progression is a succession of chords. Chord progressions are the foundation of harmony in Western musical tradition from the common practice era of Classical music to the 21st century. Chord progressions are the foundation of popular music styles, traditional music, as well as genres such as blues and jazz. In these genres, chord progressions are the defining feature on which melody and rhythm are built.

A chord, in music, is any harmonic set of pitches consisting of multiple notes that are sounded simultaneously, or nearly so. For many practical and theoretical purposes, arpeggios and other types of broken chords may also be considered as chords in the right musical context.

In music, modulation is the change from one tonality to another. This may or may not be accompanied by a change in key signature. Modulations articulate or create the structure or form of many pieces, as well as add interest. Treatment of a chord as the tonic for less than a phrase is considered tonicization.

Modulation is the essential part of the art. Without it there is little music, for a piece derives its true beauty not from the large number of fixed modes which it embraces but rather from the subtle fabric of its modulation.

A secondary chord is an analytical label for a specific harmonic device that is prevalent in the tonal idiom of Western music beginning in the common practice period: the use of diatonic functions for tonicization.

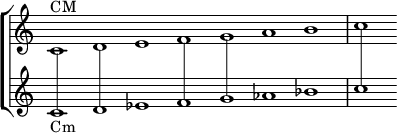

In music, relative keys are the major and minor scales that have the same key signatures, meaning that they share all the same notes but are arranged in a different order of whole steps and half steps. A pair of major and minor scales sharing the same key signature are said to be in a relative relationship. The relative minor of a particular major key, or the relative major of a minor key, is the key which has the same key signature but a different tonic.

In music theory, an augmented sixth chord contains the interval of an augmented sixth, usually above its bass tone. This chord has its origins in the Renaissance, was further developed in the Baroque, and became a distinctive part of the musical style of the Classical and Romantic periods.

In music, the mediant is the third scale degree of a diatonic scale, being the note halfway between the tonic and the dominant. In the movable do solfège system, the mediant note is sung as mi. While the fifth scale degree is almost always a perfect fifth, the mediant can be a major or minor third.

In music, the submediant is the sixth degree of a diatonic scale. The submediant is named thus because it is halfway between the tonic and the subdominant or because its position below the tonic is symmetrical to that of the mediant above.

In music, the subtonic is the degree of a musical scale which is a whole step below the tonic note. In a major key, it is a lowered, or flattened, seventh scale degree. It appears as the seventh scale degree in the natural minor and descending melodic minor scales but not in the major scale. In major keys, the subtonic sometimes appears in borrowed chords. In the movable do solfège system, the subtonic note is sung as te.

In music theory, a dominant seventh chord, or major minor seventh chord, is a seventh chord, usually built on the fifth degree of the major scale, and composed of a root, major third, perfect fifth, and minor seventh. Thus it is a major triad together with a minor seventh, denoted by the letter name of the chord root and a superscript "7". An example is the dominant seventh chord built on G, written as G7, having pitches G–B–D–F:

In music, a closely related key is one sharing many common tones with an original key, as opposed to a distantly related key. In music harmony, there are six of them: four of them share all the pitches except one with a key with which it is being compared, one of them share all the pitches, and one shares the same tonic.

In music, the dominant is the fifth scale degree of the diatonic scale. It is called the dominant because it is second in importance to the first scale degree, the tonic. In the movable do solfège system, the dominant note is sung as "So(l)".

Parallel and counter parallel chords are terms derived from the German to denote what is more often called in English the "relative", and possibly the "counter relative" chords. In Hugo Riemann's theory, and in German theory more generally, these chords share the function of the chord to which they link: subdominant parallel, dominant parallel, and tonic parallel. Riemann defines the relation in terms of the movement of one single note:

The substitution of the major sixth for the perfect fifth above in the major triad and below in the minor triad results in the parallel of a given triad. In C major thence arises an apparent A minor triad, D minor triad (Sp), and E minor triad (Dp).