An epigram is a brief, interesting, memorable, sometimes surprising or satirical statement. The word derives from the Greek ἐπίγραμμα. This literary device has been practiced for over two millennia.

Henry Fielding was an English writer and magistrate known for the use of humour and satire in his works. His 1749 comic novel The History of Tom Jones, a Foundling was a seminal work in the genre. Along with Samuel Richardson, Fielding is seen as the founder of the traditional English novel. He also played an important role in the history of law enforcement in the United Kingdom, using his authority as a magistrate to found the Bow Street Runners, London's first professional police force.

Satire is a genre of the visual, literary, and performing arts, usually in the form of fiction and less frequently non-fiction, in which vices, follies, abuses, and shortcomings are held up to ridicule, often with the intent of exposing or shaming the perceived flaws of individuals, corporations, government, or society itself into improvement. Although satire is usually meant to be humorous, its greater purpose is often constructive social criticism, using wit to draw attention to both particular and wider issues in society.

This article presents lists of literary events and publications in the 16th century.

The Greek Anthology is a collection of poems, mostly epigrams, that span the Classical and Byzantine periods of Greek literature. Most of the material of the Greek Anthology comes from two manuscripts, the Palatine Anthology of the 10th century and the Anthology of Planudes of the 14th century.

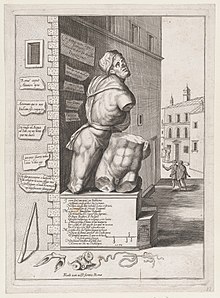

Pasquino or Pasquin is the name used by Romans since the early modern period to describe a battered Hellenistic-style statue perhaps dating to the third century BC, which was unearthed in the Parione district of Rome in the fifteenth century. It is located in a piazza of the same name on the northwest corner of the Palazzo Braschi ; near the site where it was unearthed.

John Weever (1576–1632) was an English antiquary and poet. He is best known for his Epigrammes in the Oldest Cut, and Newest Fashion (1599), containing epigrams on Shakespeare, Ben Jonson, and other poets of his day, and for his Ancient Funerall Monuments, the first full-length book to be dedicated to the topic of English church monuments and epitaphs, which was published in 1631, the year before his death.

The Satire Ménippée or La Satyre Ménippée de la vertu du Catholicon d'Espagne was a political and satirical work in prose and verse that mercilessly parodied the Catholic League and Spanish pretensions during the Wars of Religion in France, and championed the idea of an independent but Catholic France. The work was a collaborative effort of various functionaries, lawyers, clerics and scholars. It appeared at a time that coincided with the ascendance of Henry IV of France and the defeat of the League.

Decimus Junius Juvenalis, known in English as Juvenal, was a Roman poet active in the late first and early second century AD. He is the author of the collection of satirical poems known as the Satires. The details of Juvenal's life are unclear, although references within his text to known persons of the late first and early second centuries AD fix his earliest date of composition. One recent scholar argues that his first book was published in 100 or 101. A reference to a political figure dates his fifth and final surviving book to sometime after 127.

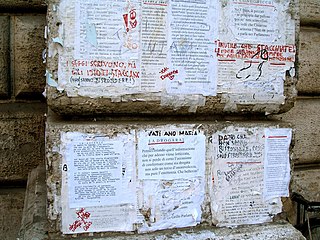

The talking statues of Rome or the Congregation of Wits provided an outlet for a form of anonymous political expression in Rome. Criticisms in the form of poems or witticisms were posted on well-known statues in Rome, as an early instance of bulletin board. It began in the 16th century and continues to the present day.

Nationality words link to articles with information on the nation's poetry or literature.

Nationality words link to articles with information on the nation's poetry or literature.

Nationality words link to articles with information on the nation's poetry or literature.

Marphurius or Marforio is one of the talking statues of Rome. Marforio maintained a friendly rivalry with his most prominent rival, Pasquin. As at the other five "talking statues", pasquinades—irreverent satires poking fun at public figures—were posted beside Marforio in the 16th and 17th centuries.

Pasquill is the pseudonym adopted by a defender of the Anglican hierarchy in an English political and theological controversy of the 1580s known as the "Marprelate controversy" after "Martin Marprelate", the nom de plume of a Puritan critic of the Anglican establishment. The names of Pasquill and his friend "Marforius", with whom he has a dialogue in the second of the tracts issued in his name, are derived from those of "Pasquino" and "Marforio", the two most famous of the talking statues of Rome, where from the early 16th century on it was customary to paste up anonymous notes or verses commenting on current affairs and scandals.

Celio Secondo Curione was an Italian humanist, grammarian, editor and historian, who exercised a considerable influence upon the Italian Reformation. A teacher in Humanities, university professor and preceptor to the nobility, he had a lively and colourful career, moving frequently between states to avoid denunciation and imprisonment: he was successively at Turin, Milan, Pavia, Venice and Lucca, before becoming a religious exile in Switzerland, first at Lausanne and finally at Basel, where he settled. He was famous and admired as a publisher and editor of works of theology and history, also for his own writings and teachings, and for the wide sphere of his friendships and correspondence with many of the most interesting reformists, Protestants and heretics of his time, though his energetic influence was at times disruptive. The imputation of antitrinitarianism is very doubtful. Curio published under the Latin form of his name, but scholarship has adopted the Italian form.

The Whores' Petition was a satirical letter addressed from brothel owners and prostitutes affected by the Bawdy House Riots of 1668, to Lady Castlemaine, lover of King Charles II of England. It requested that she come to the aid of her "sisters" and pay for the rebuilding of their property and livelihoods. Addressed from madams such as Damaris Page and Elizabeth Cresswell, it sought to mock the perceived extravagance and licentiousness of Castlemaine and the royal court.

"Paradisus Judaeorum" is a Latin phrase which became one of four members of a 19th-century Polish-language proverb that described the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth (1569–1795) as "heaven for the nobility, purgatory for townspeople, hell for peasants, paradise for Jews." The proverb's earliest attestation is an anonymous 1606 Latin pasquinade that begins, "Regnum Polonorum est". Stanisław Kot surmised that its author may have been a Catholic townsman, perhaps a cleric, who criticized what he regarded as defects of the realm; the pasquinade excoriates virtually every group and class of society.

Jiří Haussmann was a Czech writer of science fiction and satire born in Prague.