| Total population | |

|---|---|

| 551 [1] (1946) | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| Colombo · Kandy · Batticaloa | |

| Languages | |

| Tamil · Sinhala | |

| Religion | |

| Islam (Sunni) | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Pathans of Tamil Nadu · Pashtun diaspora |

The Pathans of Sri Lanka were a Muslim community in Sri Lanka of Pashtun ancestry. [2] Most of them left in the 20th century, however a small number of families living in the country still claim Pathan ancestry. [3]

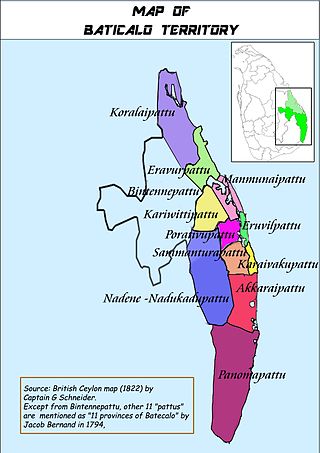

Pathan traders from what is now modern Afghanistan and Pakistan arrived by boat in eastern Sri Lanka as early as the 15th century, via Colonial India. [4] [5] They landed in Batticaloa, which was a key port. [4] Economic competition at the time led to frequent conflicts between Tamil fishing castes, particularly over control of resources. [5] One nearby village known as Eravur, inhabited by Mukkuvars, was the target of multiple attacks and looting during harvesting seasons by Thimilar folks from Batticaloa. [4] The Mukkuvars established an alliance with Batticaloa's Pathan warriors, enlisting their help to fend off the incursions and protect the village. The Thimilars were defeated and retreated northwards. [4] [lower-alpha 1]

The Mukkuvar–Pathan alliance became a key part of local folklore and temple mythology. [4] [5] The Pathans were rewarded through marriages with local women, and settled in Eravur. [4] Their settlement may have been deliberate, so as to form a buffer against future invasions from the north. [5] Some placenames in Batticaloa still appertain to the legendary battles between the Thimilars and the Mukkuvar-Pathans. [3] They achieved a strong social status, becoming prosperous landowners and merchants in the Batticaloa region. [4] [5] As the Pathans were small in number, they assimilated into the wider Muslim community and commonly self-identified as Moors. [5] [6] [7]

A similar history is recorded in Akkaraipattu, where itinerant Pathan traders helped the Mukkuvars quell a group of Vedda bandits, thereafter settling there. [5]

The arrival of Pathan settlers continued during the colonial era, mainly for purposes of trade. [2] Difficult economic conditions in their native homelands may have prompted their migration to the subcontinent's southern regions in the 19th century. [2]

The term "Pathan" is a Hindustani-origin variant of the word "Pashtun". It is used in the Indian subcontinent to refer to individuals belonging to the Pashtun ethnic group. [3] Locally, the Pathans were also known as Pattani, Pattaniyar, [3] Kabuli, or simply Afghan . [5] [8] [9] Some locals affixed the term Bhai (meaning "brother") to their names. [3] They were adherents of Sunni Islam, and mainly originated from the Khyber Pakhtunkhwa and Baluchistan in British India (modern Pakistan) [1] [10] while others came from Afghanistan. [11] The Pathans spoke Pashto and usually settled their disputes amongst themselves through a jirga system. [2] Because they were predominately men who had migrated for employment, leaving their families behind, most only stayed for a temporary period. [10] Those who decided to remain back married local women. [10]

According to M.M. Maharoof, the colonial era Pathan immigrants were able to maintain their separate cultural identity. [2] Their relationship with other Muslims was mostly confined to "the precincts of the mosque." [10] However, those who intermarried with local Muslims such as the Moors and Malays became completely integrated into these communities, [2] [10] adopting their customs and dialects (Tamil, Sinhalese or Sri Lankan Malay) [3] and lost much of their culture. [2] Only a handful of families in Sri Lanka claim Pathan ancestry today. [3]

| Year | Pop. | ±% |

|---|---|---|

| 1881 | 1,000 | — |

| 1901 | 270 | −73.0% |

| 1911 | 466 | +72.6% |

| 1921 | 304 | −34.8% |

| 1946 | 551 | +81.2% |

| Source: Census of Sri Lanka. [12] [3] | ||

In 1880, the Pathan population numbered around 1,000 in what was then British Ceylon. [2] [lower-alpha 2] They included horse keepers, textile merchants, traders, money lenders, and plantation workers in up-country estates. [2] [8] Others set up shops and grocery stores in small towns, or found work as butlers, valets, and colonial employees. [3] Around 300 of them were based in Kandy, 100 in Trincomalee and Batticaloa, 150 in Colombo, and the remaining 450 in Jaffna, Kurunegala, Badulla, Haldummulla and Ratnapura districts. [11] In 1898, the Church Missionary Review noted 64 male and ten female "Afghans" residing in Colombo. [3] Patrick Peebles states that the Pathans were recognisable by their physical and facial features, their distinctive clothing and turbans, [9] and were the subject of discriminatory usury laws. [8] They were notable for their skills in sport, [11] engaging in games such as wrestling or buzkashi, [3] and usually lived together. [13] The Pathans belonged to different tribes, including Afridi, Khilji, Yousafzai, Ahmadzai and Kakar, and the surname Khan was common amongst them. [3] In 1901, their population had decreased to about 270. [3]

A 1911 Census report described them as follows:

They are well known figures in the streets of Colombo and Kandy and in estate bazaars. They are tall and well formed... Their dress is distinctive – a loose tunic, baggy drawers, and thick boots. Their head dress is wound in rolls round the head, generally over a small skull-cap. There are some excellent wrestlers amongst them. They have their own chiefs and settle disputes amongst themselves. Their occupation they usually give as cloth sellers or horse traders, but their principal business is usury; they are the petty money lenders of the country. [12]

In addition to plying trade in provincial cities like Colombo (including Slave Island) [9] and Kandy, the community was also scattered itinerantly across hill country towns like Passara and Bandarawela. [2] In 1921, the population was recorded at 304 individuals, decreasing from 466 in the previous census. [12] Many Pathans returned home during the 1940s, while some migrated to India. [8] [9]

The 1946 Census identified 551 Pathans living on the island, the majority of them concentrated in Colombo and urban centres. [1] [10] They were primarily money lenders and creditors, a profession not traditionally occupied by natives, [1] [6] [14] and were noted to be prosperous. [3] Some were recruited as guards due to their imposing appearance, or worked in the postal service. [3] [10] K. P. S. Menon notes that the Ceylonese "did not mind borrowing money" from the Pathan lenders, but kept them at a distance as they were known to charge high interest rates. In fact, "almost the entire railway staff was in debt" to them, and "shut their eyes when their creditors traveled without tickets." [1] The non-payment of dues was a matter that often ruthlessly invoked the taking of law into their own hands, which made the Ceylonese wary of them a great deal. [11] [14]

Islam is the third largest religion in Sri Lanka, with about 9.7 percent of the total population following the religion. About 1.9 million Sri Lankans adhere to Islam as per the Sri Lanka census of 2012. The majority of Muslims in Sri Lanka are concentrated in the Eastern Province of the island. Other areas containing significant Muslim minorities include the Western, Northwestern, North Central, Central and Sabaragamuwa provinces. Muslims form a large segment of the urban population of Sri Lanka and are mostly concentrated in major cities and large towns in Sri Lanka, for example Colombo. Most Sri Lankan Muslims primarily speak Tamil language, though it is not uncommon for Sri Lankan Muslims to be fluent in Sinhalese.

Batticaloa is a major city in the Eastern Province, Sri Lanka, and its former capital. It is the administrative capital of the Batticaloa District. The city is the seat of the Eastern University of Sri Lanka and is a major commercial centre. It is on the east coast, 111 kilometres (69 mi) south of Trincomalee, and is situated on an island. Pasikudah is a popular tourist destination situated 35 km (22 mi) northwest with beaches and flat year-round warm-water shallow-lagoons.

The caste systems in Sri Lanka are social stratification systems found among the ethnic groups of the island since ancient times. The models are similar to those found in Continental India, but are less extensive and important for various reasons, although the caste systems still play an important and at least symbolic role in religion and politics. Sri Lanka is often considered to be a casteless or caste-blind society by Indians.

The Sri Lankan Kaffirs are an ethnic group in Sri Lanka who are partially descended from 16th-century Portuguese traders and Bantu slaves who were brought by them to work as labourers and soldiers to fight against the Sinhala Kings. They are very similar to the Zanj-descended populations in Iraq and Kuwait, and are known in Pakistan as Sheedis and in India as Siddis. The Kaffirs spoke a distinctive creole based on Portuguese, and the "Sri Lankan Kaffir language". Their cultural heritage includes the dance styles Kaffringna and Manja and their popular form of dance music Baila.

Sri Lankan Mukkuvar is a Tamil speaking ethnic group found in the Western and Eastern coastal regions of Sri Lanka. They are primarily concentrated in the districts of Batticaloa, Ampara and Puttalam. They are also related to "Sri Lankan Moors". Sri Lankan Mukkuvars along with Eastern Muslims of Sri Lankan claim their origin from Kerala and matrilineal in practice. Recent studies show their habits and clan structure, as well as dialects, show affinity towards the Northern Kerala regions.

Karava is a Sinhalese speaking ethnic group of Sri Lanka, whose ancestors migrated from the Coromandel coast, claiming lineage to the Kaurava royalty of the old Kingdom of Kuru in Northern India. The Tamil equivalent is Karaiyar. Both groups are also known as the Kurukula.

Sri Lankan Moors are an ethnic minority group in Sri Lanka, comprising 9.2% of the country's total population. Most of them are native speakers of the Tamil language who also speak Sinhalese as a second language. They are predominantly followers of Islam. The Sri Lankan Muslim community is divided as Sri Lankan Moors, Indian Moors and Sri Lankan Malays depending on their history and traditions.

Seyed Ali Zahir Moulana is a Sri Lankan politician, former diplomat and local government activist. He is most known for the pivotal and important role he played in bringing about an end to the Sri Lankan Civil War.

Batticaloa District is one of the 25 districts of Sri Lanka, the second level administrative division of the country. The district is administered by a District Secretariat headed by a District Secretary appointed by the central government of Sri Lanka. The capital of the district is the city of Batticaloa. Ampara District was carved out of the southern part of Batticaloa District in April 1961.

History of Eastern Tamils of Sri Lanka is informed by local legends, native literature and other colonial documents. Sri Lankan Tamils are subdivided based on their cultural, dialects & other practices as into Northern, Eastern and Western groups. Eastern Tamils inhabit a region that is divided into Trincomalee District, Batticalo District and Ampara District.

Vanniar or Vanniyar was a title borne by chiefs in medieval Sri Lanka who ruled in the Chiefdom of Vavuni regions as tribute payers to the Jaffna vassal state. There are a number of origin theories for the feudal chiefs, coming from an indigenous formation. The most famous of the Vavni chieftains was Pandara Vannian, known for his resistance against the British colonial power.

The Vanni chieftaincies or Vanni principalities was a region between Anuradhapura and Jaffna, but also extending to along the eastern coast to Panama and Yala, during the Transitional and Kandyan periods of Sri Lanka. The heavily forested land was a collection of chieftaincies of principalities that were a collective buffer zone between the Jaffna Kingdom, in the north of Sri Lanka, and the Sinhalese kingdoms in the south. Traditionally the forest regions were ruled by Vedda rulers. Later on, the emergence of these chieftaincies were a direct result of the breakdown of central authority and the collapse of the Kingdom of Polonnaruwa in the 13th century, as well as the establishment of the Jaffna Kingdom in the Jaffna Peninsula. Control of this area was taken over by dispossessed Sinhalese nobles and chiefs of the South Indian military of Māgha of Kalinga (1215–1236), whose 1215 invasion of Polonnaruwa led to the kingdom's downfall. Sinhalese chieftaincies would lay on the northern border of the Sinhalese kingdom while the Tamil chieftaincies would border the Jaffna Kingdom and the remoter areas of the eastern coast, north western coast outside of the control of either kingdom.

Tuan Burhanuddin Jayah, was a Sri Lankan educationalist, politician, diplomat and Muslim community leader and considered one of Sri Lanka's national heroes. He started his career as a school teacher and retired after serving 27 years as the principal of Zahira College, Colombo. Under his stewardship, Zahira College became one of the leading schools in the country.

Ja-Ela is a town, located approximately 20 km (12 mi) north of the Colombo city centre. Ja-Ela lies on the A3 road which overlaps with the Colombo – Katunayake Expressway at the Ja-Ela Interchange.

Indians in Sri Lanka refer to Indians or people of Indian ancestry living in Sri Lanka, such as the Indian Tamils of Sri Lanka.

Dr. Al-Haj Mohamed Purvis Drahaman was a Ceylonese Malay medical doctor and politician. He was the leader of the All Ceylon Malay Congress, and was appointed as Member of Parliament in 1956 and 1960.

The 1915 Sinhalese-Muslim riots was a widespread and prolonged ethnic riot in the island of Ceylon between Sinhalese Buddhists and the Ceylon Moors. The riots were eventually suppressed by the British colonial authorities.

Batticaloa region (Tamil: மட்டக்களப்புத் தேசம் Maṭṭakkaḷapput tēcam; also known as Matecalo; Baticalo; in colonial records, was the ancient region of Tamil settlements in Sri Lanka. The foremost record of this region can be seen in Portuguese and Dutch historical documents along with local inscriptions such as "Sammanthurai Copper epigraphs" written in 1683 CE which also mentions "Mattakkalappu Desam". Although there is no more the existence of Batticaloa region today, the amended term "Batti-Ampara Districts" also as “Keezhakarai” can still be seen in the Tamil print media of Sri Lanka.

The term "Afghan" refers to those people of the North-West Frontier region of the Indian sub-continent who have settled in the island. This includes Pathans and Baluchis who form the largest group amongst them.

Besides Moors, the Muslim community in Sri Lanka contains a sizeable number of Malays, Bohras, and Memons as well as recent migrants such as Coast Moors, Khojas and Afghans.

At one time there was a flourishing group commonly referred to as "Afghans." These were Muslims from Baluchistan who carried out small money lending businesses... Along with their money lending business, there were others who worked as Watchers.

The Afghans had originally come to Ceylon as horse- keepers from different parts of Afghanistan. On arrival some of them took to petty trading and penetrated into the remote Kandyan villages, taking for sale textiles of Indian manufacture... In 1880 on 13th and 14th November, nearly 150 Afghans gathered in Kandy for a festival and indulged in games of skill.

Their numbers in 1921 show a decrease from 466 to 304, but it is clear that the persons generally known in Ceylon as " Afghans " have, in many cases, rightly or wrongly, been described as Baluchis, or some other Indian race.

There are the Muslims from Baluchistan who are called Afghans in Ceylon. They are chiefly engaged in lending money at high interest...