Dithmarschen is a district in Schleswig-Holstein, Germany. It is bounded by the districts of Nordfriesland, Schleswig-Flensburg, Rendsburg-Eckernförde, and Steinburg, by the state of Lower Saxony, and by the North Sea. From the 13th century up to 1559 Dithmarschen was an independent peasant republic within the Holy Roman Empire and a member of the Hanseatic League.

Frisia is a cross-border cultural region in Northwestern Europe. Stretching along the Wadden Sea, it encompasses the north of the Netherlands and parts of northwestern Germany. Wider definitions of ‘Frisia’ may include the island of Rem and the other Danish Wadden Sea Islands. The region is traditionally inhabited by the Frisians, a West Germanic ethnic group.

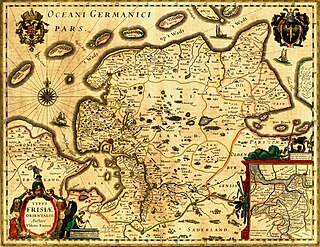

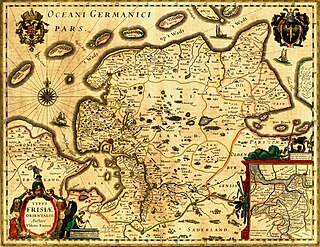

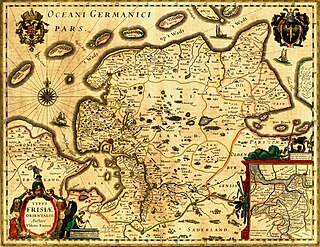

East Frisia or East Friesland is a historic region in the northwest of Lower Saxony, Germany. It is primarily located on the western half of the East Frisian peninsula, to the east of West Frisia and to the west of Landkreis Friesland.

A terp, also known as a wierde, woerd, warf, warft, werf, werve, wurt or værft, is an artificial dwelling mound found on the North European Plain that has been created to provide safe ground during storm surges, high tides and sea or river flooding. The various terms used reflect the regional dialects of the North European region.

Land Wursten is a former Samtgemeinde in the district of Cuxhaven, in Lower Saxony, Germany. It was situated approximately 20 km (12 mi) southwest of Cuxhaven, and 15 km (9.3 mi) north of Bremerhaven. Its seat was in the village Dorum. It was disbanded in January 2015, when its member municipalities merged into the new municipality Wurster Nordseeküste.

Henry IV, called the Elder, a member of the House of Welf, was Duke of Brunswick-Lüneburg and ruling Prince of Wolfenbüttel from 1491 until his death.

Midlum is a village and a former municipality in the district of Cuxhaven, in Lower Saxony, Germany. Since 1 January 2015 it is part of the municipality Wurster Nordseeküste.

Frisia has changed dramatically over time, both through floods and through a change in identity. It is part of the Nordwestblock which is a hypothetical historic region linked by language and culture,where they may have spoken an Indo-European language which was neither germanic nor celtic.

The County of East-Frisia was a county in the region of East Frisia in the northwest of the present-day German state of Lower Saxony.

Eric IV of Saxe-Lauenburg was a son of Eric II, Duke of Saxe-Lauenburg and Agnes of Holstein.

Land Hadeln is a historic landscape and former administrative district in Northern Germany with its seat in Otterndorf on the Lower Elbe, the lower reaches of the River Elbe, in the Elbe-Weser Triangle between the estuaries of the Elbe and Weser.

The history of East Frisia developed rather independently from the rest of Germany because the region was relatively isolated for centuries by large stretches of bog to the south, while at the same time its people were oriented towards the sea. Thus in East Frisia in the Middle Ages there was little feudalism, instead a system of fellowship under the so-called Friesian Freedom emerged. It was not until 1464, that the House of Cirksena was enfeoffed with the Imperial County of East Frisia. Nevertheless absolutism had been, and continued to be, unknown in East Frisia. In the two centuries after about 1500, the influence of the Netherlands is discernable - politically, economically and culturally. In 1744, the county lost its independence within the Holy Roman Empire and became part of Prussia. Following the Vienna Congress of 1815, it was transferred to the Kingdom of Hanover, in 1866 it went back to Prussia and, from 1946, it has been part of the German state of Lower Saxony.

The flags of Frisia are the flags that are used to represent Frisia, a cross-border cultural region in Northwestern Europe. Some designs are in official use on a local or provincial level, while others are used unofficially on a regional, linguistic or international level.

Johann Rode von Wale was a Catholic cleric, a Doctor of Canon and Civil Law, a chronicler, a long-serving government official (1468–1497) and as John III Prince-archbishop of Bremen between 1497 and 1511.

The Saxon feud was a military conflict in the years 1514–1517 between the East Frisian Count Edzard I, 'West Frisian' rebels, the city of Groningen, and Charles II, Duke of Guelders on the one hand and the Imperial Frisian hereditary governor George, Duke of Saxony – replaced by Charles V of Habsburg in 1515 – and 24 German princes. The war took place predominantly on East Frisian soil and destroyed large parts of the region.

John V, Count of Oldenburg and Delmenhorst was a member of the House of Oldenburg. He was the ruling Count of Oldenburg from 1500 to 1526. His parents were Gerhard VI, Count of Oldenburg and Adelheid of Tecklenburg.

The Lordship of Frisia or Lordship of Friesland was a feudal dominion in the Netherlands. It was formed in 1498 by King Maximilian I and reformed in 1524 when Emperor Charles V conquered Frisia.

The Interfrisian Council is a geopolitical organization that represents the common interests of the Frisians. The organization consists of three regional councils or "sections": North Frisia, East Frisia and West Frisia. Every three years, the presidency of the Interfrisian Council is handed over to another section. The council was established in 1956.

The Stedinger Crusade (1233–1234) was a Papally sanctioned war against the rebellious peasants of Stedingen.