The Philippines, officially the Republic of the Philippines, is an archipelagic country in Southeast Asia. It is situated in the western Pacific Ocean, and consists of about 7,640 islands, that are broadly categorized under three main geographical divisions from north to south: Luzon, Visayas, and Mindanao. The Philippines is bounded by the West Philippine Sea to the west, the Philippine Sea to the east, and the Celebes Sea to the southwest, and shares maritime borders with Taiwan to the north, Japan to the northeast, Palau to the east and southeast, Indonesia to the south, Malaysia to the southwest, Vietnam to the west, and China to the northwest. The Philippines covers an area of 300,000 km2 (120,000 sq mi) and, as of 2020, had a population of around 109 million people, making it the world's twelfth-most populous country. The Philippines is a multinational state, with diverse ethnicities and cultures throughout its islands. Manila is the nation's capital, while the largest city is Quezon City, both lying within the urban area of Metro Manila.

Demography of the Philippines records the human population, including its population density, ethnicity, education level, health, economic status, religious affiliations, and other aspects. The Philippines annualized population growth rate between the years 2015–2020 was 1.63%. According to the 2020 census, the population of the Philippines is 109,035,343. The first census in the Philippines was held in the year 1591 which counted 667,612 people.

Asian Americans are Americans of Asian ancestry. Although this term had historically been used for all the indigenous peoples of the continent of Asia, the usage of the term "Asian" by the United States Census Bureau excludes people with ethnic origins in certain parts of Asia, including West Asia who are now categorized as Middle Eastern Americans; and those from Central Asia who are categorized as Central Asian Americans. The "Asian" census category includes people who indicate their race(s) on the census as "Asian" or reported entries such as "Chinese, Indian, Filipino, Vietnamese, Indonesian, Korean, Japanese, Pakistani, Malaysian, and Other Asian". In 2018, Asian Americans were 5.4% of the U.S. population; including multiracial Asian Americans, that percentage increases to 6.5%. In 2020, the estimated number of Asian Americans was 24 million.

The Japanese diaspora and its individual members known as nikkei (日系) or as nikkeijin (日系人), comprise the Japanese emigrants from Japan residing in a country outside Japan. Emigration from Japan was recorded as early as the 15th century to the Philippines, but did not become a mass phenomenon until the Meiji period (1868–1912), when Japanese emigrated to the Philippines and to the Americas. There was significant emigration to the territories of the Empire of Japan during the period of Japanese colonial expansion (1875-1945); however, most of these emigrants repatriated to Japan after the 1945 surrender of Japan ended World War II in Asia.

Filipino Americans are Americans of Filipino ancestry. Filipinos in North America were first documented in the 16th century and other small settlements beginning in the 18th century. Mass migration did not begin until after the end of the Spanish–American War at the end of the 19th century, when the Philippines was ceded from Spain to the United States in the Treaty of Paris.

Asian immigration to the United States refers to immigration to the United States from part of the continent of Asia, which includes East Asia, Southeast Asia, and South Asia. Historically, immigrants from other parts of Asia, such as West Asia were once considered "Asian", but are considered immigrants from the Middle East. Asian-origin populations have historically been in the territory that would eventually become the United States since the 16th century. The first major wave of Asian immigration occurred in the late 19th century, primarily in Hawaii and the West Coast. Asian Americans experienced exclusion, and limitations to immigration, by the United States law between 1875 and 1965, and were largely prohibited from naturalization until the 1940s. Since the elimination of Asian exclusion laws and the reform of the immigration system in the Immigration and Nationality Act of 1965, there has been a large increase in the number of immigrants to the United States from Asia.

American settlement in the Philippines began during the Spanish colonial period. The period of American colonialization of the Philippines was 48 years. It began with the cession of the Philippines to the U.S. by Spain in 1898 and lasted until the U.S. recognition of Philippine independence in 1946. After independence in 1946, many Americans chose to remain in the Philippines while maintaining relations with relatives in the US. Most of them were professionals, but missionaries continued to settle the country. In 2015, the U.S. State Department estimated that there were more than 220,000 U.S. citizens living in the Philippines, with a significant mixed population of Amerasians and descendants from the colonial era as well.

Asian American and Pacific Islander Heritage Month is a period for the duration of the month of May for recognizing the contributions and influence of Asian Americans and Pacific Islander Americans to the history, culture, and achievements of the United States.

During the United States colonial period of the Philippines (1898–1946), the United States government was in charge of providing education in the Philippines.

The demographics of Asian Americans describe a heterogeneous group of people in the United States who trace their ancestry to one or more Asian countries.

Asian-American history is the history of ethnic and racial groups in the United States who are of Asian descent. Spickard (2007) shows that "'Asian American' was an idea invented in the 1960s to bring together Chinese, Japanese, and Filipino Americans for strategic political purposes. Soon other Asian-origin groups, such as Korean, Vietnamese, Iu Mien, Hmong and South Asian Americans, were added." For example, while many Chinese, Japanese, and Filipino immigrants arrived as unskilled workers in significant numbers from 1850 to 1905 and largely settled in Hawaii and California, many Vietnamese, Cambodian, and Hmong Americans arrived in the United States as refugees following the Vietnam War. These separate histories have often been overlooked in conventional frameworks of Asian American history.

Asian Americans, who are Americans of Asian descent, have fought and served on behalf of the United States since the War of 1812. During the American Civil War Asian Americans fought for both the Union and the Confederacy. Afterwards Asian Americans served primarily in the U.S. Navy until the Philippine–American War.

The history of Filipino Americans begins in the 16th century when Filipinos first arrived in what is now the United States. The first Filipinos came to what is now the United States due to the Philippines being part of New Spain. Until the 19th century, the Philippines continued to be geographically isolated from the rest of New Spain in the Americas but maintained regular communication across the Pacific Ocean via the Manila galleon. Filipino seamen in the Americas settled in Louisiana, and Alta California, beginning in the 18th century. By the 19th century, Filipinos were living in the United States, fighting in the Battle of New Orleans and the American Civil War, with the first Filipino becoming a naturalized citizen of the United States before its end. In the final years of the 19th century, the United States went to war with Spain, ultimately annexing the Philippine Islands from Spain. Due to this, the History of the Philippines merged with that of the United States, beginning with the three-year-long Philippine–American War (1899-1902), which resulted in the defeat of the First Philippine Republic, and the attempted Americanization of the Philippines.

The 1st Filipino Infantry Regiment was a segregated United States Army infantry regiment made up of Filipino Americans from the continental United States and a few veterans of the Battle of the Philippines that saw combat during World War II. It was formed and activated at Camp San Luis Obispo, California, under the auspices of the California National Guard. Originally created as a battalion, it was declared a regiment on 13 July 1942. Deployed initially to New Guinea in 1944, it became a source of manpower for special forces and units that would serve in occupied territories. In 1945, it deployed to the Philippines, where it first saw combat as a unit. After major combat operations, it remained in the Philippines until it returned to California and was deactivated in 1946 at Camp Stoneman.

The demographics of Filipino Americans describe a heterogeneous group of people in the United States who trace their ancestry to the Philippines. As of the 2010 Census, there were 3.4 million Filipino Americans, including Multiracial Americans who were part Filipino living in the US; in 2011 the United States Department of State estimating the population at four million. Filipino Americans constitute the second-largest population of Asian Americans, and the largest population of Overseas Filipinos.

Anti-Filipino sentiment refers to the general dislike or hatred towards the Philippines, Filipinos or Filipino culture. This can come in the form of direct slurs or persecution, in the form of connoted microaggressions, or depictions of the Philippines or the Filipino people as being inferior in some form psychologically, culturally or physically.

Filipino Americans have a long history of music in the United States. The Philippines have musical context and varied influences due to indigenous traditions and early colonial influences of Spanish and American occupation. During occupation by the United States, many Filipinos were recruited for manual labor along the West Coast. These early laborers commonly would perform Spanish-influenced rondallas as well as choral groups. With many Filipinos living in the United States beginning around the 1900s, Filipinos have contributed towards early Americana staples such as blues and jazz, and continue to influence more modern contemporary genres such as hip hop and rock. American music has also been influential in the Philippines for artists and vice versa. Though contributing to the evolution of American music, large number of Filipino Americans have a strong identity with culture of the Philippines by participating or organizing traditional dances and musical performances, largely in the form of PCNs on university campuses. Traditional dances and musical performances commonly practiced in the US are rondallas, choral groups, and gong chime ensembles. College campuses often organize performances on campuses, but can also have characteristics unique to America, as many Filipino Americans want to share their experiences of living in America and perform a more neo traditional variation of traditional performances.

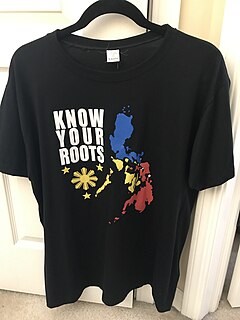

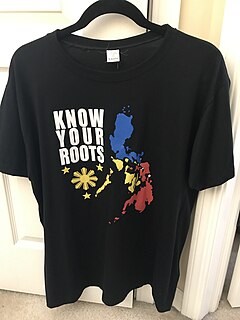

Fashion and clothing for Filipino-Americans has been a symbol of political action since their arrival to the U.S. in the early 20th century. Dealing with U.S. occupation in the Philippines, both students and laborers adopted American styles of dress while also maintaining styles of dress that originated in the Philippines. Fashion remains an integral aspect for the Filipino-American community, with many cultural celebrations regarding fashion such as Canada Philippine Fashion Week in Toronto and other fashion weeks occurring in numerous global cities. Aside from partaking in fashion, the Philippines also produces clothing that is made for mass consumption overseas, in places such as the U.S., Europe, and Canada.

Hokkien, Hoklo (Holo), and Minnan people are found in the United States. The Hoklo people are a Han Chinese subgroup with ancestral roots in Southern Fujian and Eastern Guangdong, particularly around the modern prefecture-level cities of Quanzhou, Zhangzhou, Xiamen and Chaoshan area. They are also known by various endonyms, or other related terms such as Hoklo people (河洛儂), Banlam (Minnan) people, Hokkien people or Teochew people (潮州人;Tiê-tsiu-lâng). These people usually also have roots in the Hokkien diaspora in Taiwan, the Philippines, Malaysia, Indonesia, Singapore, Burma, Thailand, Vietnam, and Cambodia.

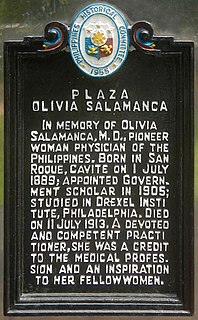

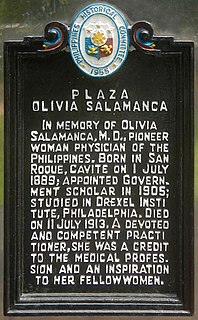

Olivia Salamanca was a Filipino physician who trained in the United States at the Woman's Medical College of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia and was the second female physician from the Philippines. She died from tuberculosis at the age of 24.