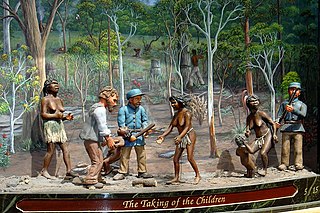

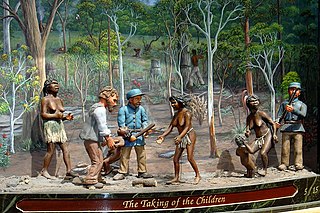

The Stolen Generations were the children of Australian Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander descent who were removed from their families by the Australian federal and state government agencies and church missions, under acts of their respective parliaments. The removals of those referred to as "half-caste" children were conducted in the period between approximately 1905 and 1967, although in some places mixed-race children were still being taken into the 1970s.

Rabbit-Proof Fence is a 2002 Australian drama film directed and produced by Phillip Noyce based on the 1996 book Follow the Rabbit-Proof Fence by Doris Pilkington Garimara. It is loosely based on a true story concerning the author's mother Molly Craig, as well as two other Aboriginal girls, Daisy Kadibil and Gracie, who escape from the Moore River Native Settlement, north of Perth, Western Australia, to return to their Aboriginal families, after being placed there in 1931. The film follows the Aboriginal girls as they walk for nine weeks along 1,500 miles (2,400 km) of the Australian rabbit-proof fence to return to their community at Jigalong, while being pursued by white law enforcement authorities and an Aboriginal tracker. The film illustrates the official child removal policy that existed in Australia between approximately 1905 and 1967. Its victims now are called the "Stolen Generations".

Keith Windschuttle is an Australian historian. He was appointed to the board of the Australian Broadcasting Corporation in 2006. He was editor of Quadrant from 2007 to 2015 when he became chair of the board and editor-in-chief. He was the publisher of Macleay Press, which operated from 1994 to 2010.

Robert Michael Manne is an Emeritus Professor of politics and Vice-Chancellor's Fellow at La Trobe University, Melbourne, Australia. He is a leading Australian public intellectual.

National Sorry Day, officially the National Day of Healing, is an event held annually in Australia on 26 May commemorating the Stolen Generations. It is part of the ongoing efforts towards reconciliation between Indigenous and non-Indigenous Australians.

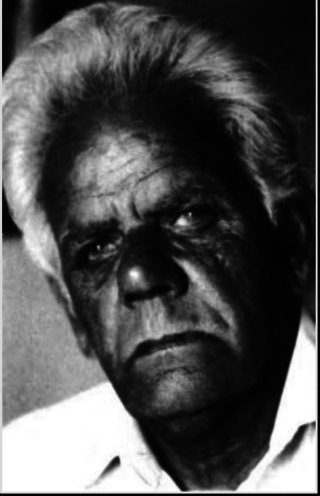

Jack Leonard Davis was an Australian 20th-century Aboriginal playwright, poet and Aboriginal Australian activist. Academic Adam Shoemaker, who has covered much of Jack Davis‘ work and Aboriginal literature, has claimed he was one of “Australia’s most influential Aboriginal authors”. He was born in Perth, Western Australia, where he spent most of his life and later died. He identified with the Western Australian Noongar people, and he included some of this language into his plays. His work incorporates themes of Aboriginality and identity.

The history wars is a term used in Australia to describe the public debate about the interpretation of the history of the European colonisation of Australia and the development of contemporary Australian society, particularly with regard to their impact on Aboriginal Australian and Torres Strait Islander peoples. The term "history wars" emerged in the late 1990s during the term of the Howard government, and the debate is ongoing.

William Edward Hanley Stanner CMG, often cited as W.E.H. Stanner, was an Australian anthropologist who worked extensively with Indigenous Australians. Stanner had a varied career that also included journalism in the 1930s, military service in World War II, and political advice on colonial policy in Africa and the South Pacific in the post-war period.

Bringing Them Home is the 1997 Australian Report of the National Inquiry into the Separation of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Children from Their Families. The report marked a pivotal moment in the controversy that has come to be known as the Stolen Generations.

Indigenous Australians are people with familial heritage from, and membership in, the ethnic groups that lived in areas within the Australian continent before British colonisation. They consist of two distinct groups: the Aboriginal peoples of the Australian mainland and Tasmania, and the Torres Strait Islander peoples from the seas between Queensland and Papua New Guinea. The term Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples or the person's specific cultural group, is often preferred, though the terms First Nations of Australia, First Peoples of Australia and First Australians are also increasingly common; 812,728 people self-identified as being of Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander origin in the 2021 Australian Census, representing 3.2% of the total population of Australia. Of these Indigenous Australians, 91.4% identified as Aboriginal; 4.2% identified as Torres Strait Islander; while 4.4% identified with both groups. Since 1995, the Australian Aboriginal flag and the Torres Strait Islander flag have been official flags of Australia.

Brian Gregory Syron was an actor, teacher, Aboriginal rights activist, stage director and Australia's first Indigenous feature film director, who has also been recognised as the first First Nations feature film director. After studying in New York City under Stella Adler, he returned to Australia and was a co-founder of the Australian National Playwrights Conference, the Eora Centre, the National Black Playwrights Conference, and the Aboriginal National Theatre Trust. He worked on several television productions and was appointed head of the ABC's new Aboriginal unit in 1988.

The Other Side of the Frontier is a history book published in 1981 by Australian historian Henry Reynolds. It is a study of Aboriginal Australian resistance to the British settlement, or invasion, of Australia from 1788 onwards.

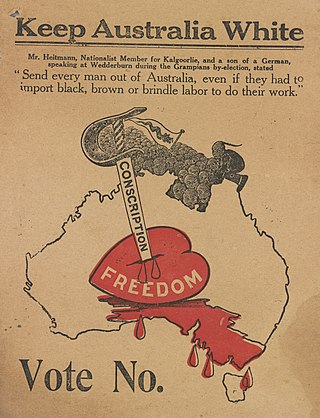

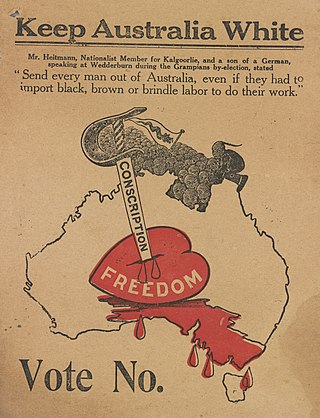

Racism in Australia comprises negative attitudes and views on race or ethnicity which are related to each other, are held by various people and groups in Australia, and have been reflected in discriminatory laws, practices and actions at various times in the history of Australia against racial or ethnic groups.

BarbaraWeir is an Australian Aboriginal artist and politician. One of the Stolen Generations, she was removed from her Aboriginal family and raised in a series of foster homes. In the 1970s Weir returned to her family territory of Utopia, 300 kilometres (190 mi) northeast of Alice Springs. She became active in the local land rights movement of the 1970s and was elected the first woman president of the Indigenous Urapunta Council in 1985. After starting to paint in her mid-forties, she also gained recognition as a notable artist of Central Australia. She also managed the artistic career of her own mother, Minnie Pwerle, who was also a noted artist.

Kenneth George Wyatt is an Australian former politician. He was a member of the House of Representatives from 2010 to 2022, representing the Division of Hasluck for the Liberal Party. He is the first Indigenous Australian elected to the House of Representatives, the first to serve as a government minister, and the first appointed to cabinet.

Diane Elizabeth McEachern Barwick was a Canadian-born anthropologist, historian, and Aboriginal-rights activist. She was also a renowned researcher and teacher in the field of Australian Aboriginal culture and society.

Cecil Evelyn Aufrere (Mick) Cook was an Australian physician and medical administrator, who specialised in tropical diseases and public health. He was appointed as Chief Medical Officer and Protector of Aborigines for the Northern Territory in 1927. He established much of the infrastructure of the public health system there, including four hospitals, a tuberculosis clinic, a nursing school and the Nurses’ Board of North Australia. He started the Northern Territory Aerial Medical Service together with Dr Clyde Fenton, and he was founding chairman of the Northern Territory Medical Board.

Thomas Edwin Calma,, is an Aboriginal Australian human rights and social justice campaigner, and 2023 senior Australian of the Year. He is the sixth chancellor of the University of Canberra, a post held since January 2014, after two years as deputy chancellor. Calma is the second Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander person to hold the position of chancellor of any Australian university.

On 13 February 2008, the Parliament of Australia issued a formal apology to Indigenous Australians for forced removals of Australian Indigenous children from their families by Australian federal and state government agencies. The apology was delivered by Prime Minister Kevin Rudd, and is also referred to as the National Apology, or simply The Apology.

Charles Frederick Maynard, an Aboriginal Australian activist who advocated for land rights, citizenship and equal rights for Aboriginal Australian people. He is known for being the founder of the Australian Aboriginal Progressive Association (AAPA) in Sydney, New South Wales.