In geology, felsic is a modifier describing igneous rocks that are relatively rich in elements that form feldspar and quartz. It is contrasted with mafic rocks, which are relatively richer in magnesium and iron. Felsic refers to silicate minerals, magma, and rocks which are enriched in the lighter elements such as silicon, oxygen, aluminium, sodium, and potassium. Felsic magma or lava is higher in viscosity than mafic magma/lava.

Sandstone is a clastic sedimentary rock composed mainly of sand-sized silicate grains. Sandstones comprise about 20–25% of all sedimentary rocks.

Trachyte is an extrusive igneous rock composed mostly of alkali feldspar. It is usually light-colored and aphanitic (fine-grained), with minor amounts of mafic minerals, and is formed by the rapid cooling of lava enriched with silica and alkali metals. It is the volcanic equivalent of syenite.

Nepheline syenite is a holocrystalline plutonic rock that consists largely of nepheline and alkali feldspar. The rocks are mostly pale colored, grey or pink, and in general appearance they are not unlike granites, but dark green varieties are also known. Phonolite is the fine-grained extrusive equivalent.

In petrology, spherulites are small, rounded bodies that commonly occur in vitreous igneous rocks. They are often visible in specimens of obsidian, pitchstone, and rhyolite as globules about the size of millet seed or rice grain, with a duller luster than the surrounding glassy base of the rock, and when they are examined with a lens they prove to have a radiate fibrous structure.

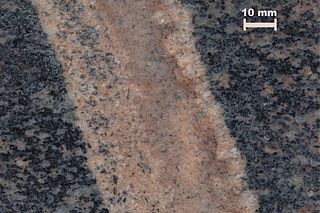

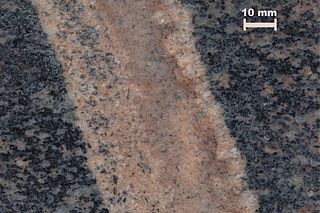

Aplite is an intrusive igneous rock in which the mineral composition is the same as granite, but in which the grains are much finer, under 1 mm across. Quartz and feldspar are the dominant minerals. The term aplite or aplitic is often used as a textural term to describe veins of quartz and feldspar with a fine to medium-grain "sugary" texture. Aplites are usually very fine-grained, white, grey or pinkish, and their constituents are visible only with the help of a magnifying lens. Dykes and veins of aplite are commonly observed traversing granitic bodies; they occur also, though less frequently, in syenites, diorites, quartz diabases, and gabbros.

The scapolites are a group of rock-forming silicate minerals composed of aluminium, calcium, and sodium silicate with chlorine, carbonate and sulfate. The two endmembers are meionite and marialite. Silvialite (Ca,Na)4Al6Si6O24(SO4,CO3) is also a recognized member of the group.

Granulites are a class of high-grade metamorphic rocks of the granulite facies that have experienced high-temperature and moderate-pressure metamorphism. They are medium to coarse–grained and mainly composed of feldspars sometimes associated with quartz and anhydrous ferromagnesian minerals, with granoblastic texture and gneissose to massive structure. They are of particular interest to geologists because many granulites represent samples of the deep continental crust. Some granulites experienced decompression from deep in the Earth to shallower crustal levels at high temperature; others cooled while remaining at depth in the Earth.

Hornfels is the group name for a set of contact metamorphic rocks that have been baked and hardened by the heat of intrusive igneous masses and have been rendered massive, hard, splintery, and in some cases exceedingly tough and durable. These properties are caused by fine grained non-aligned crystals with platy or prismatic habits, characteristic of metamorphism at high temperature but without accompanying deformation. The term is derived from the German word Hornfels, meaning "hornstone", because of its exceptional toughness and texture both reminiscent of animal horns. These rocks were referred to by miners in northern England as whetstones.

Lamprophyres are uncommon, small-volume ultrapotassic igneous rocks primarily occurring as dikes, lopoliths, laccoliths, stocks, and small intrusions. They are alkaline silica-undersaturated mafic or ultramafic rocks with high magnesium oxide, >3% potassium oxide, high sodium oxide, and high nickel and chromium.

Arkose or arkosic sandstone is a detrital sedimentary rock, specifically a type of sandstone containing at least 25% feldspar. Arkosic sand is sand that is similarly rich in feldspar, and thus the potential precursor of arkose.

Quartz-porphyry, in layman's terms, is a type of volcanic (igneous) rock containing large porphyritic crystals of quartz. These rocks are classified as hemi-crystalline acid rocks.

The Folk classification, in geology, is a technical descriptive classification of sedimentary rocks devised by Robert L. Folk, an influential sedimentary petrologist and Professor Emeritus at the University of Texas.

Clastic rocks are composed of fragments, or clasts, of pre-existing minerals and rock. A clast is a fragment of geological detritus, chunks, and smaller grains of rock broken off other rocks by physical weathering. Geologists use the term clastic to refer to sedimentary rocks and particles in sediment transport, whether in suspension or as bed load, and in sediment deposits.

In optical mineralogy and petrography, a thin section is a thin slice of a rock or mineral sample, prepared in a laboratory, for use with a polarizing petrographic microscope, electron microscope and electron microprobe. A thin sliver of rock is cut from the sample with a diamond saw and ground optically flat. It is then mounted on a glass slide and then ground smooth using progressively finer abrasive grit until the sample is only 30 μm thick. The method uses the Michel-Lévy interference colour chart to determine thickness, typically using quartz as the thickness gauge because it is one of the most abundant minerals.

Optical mineralogy is the study of minerals and rocks by measuring their optical properties. Most commonly, rock and mineral samples are prepared as thin sections or grain mounts for study in the laboratory with a petrographic microscope. Optical mineralogy is used to identify the mineralogical composition of geological materials in order to help reveal their origin and evolution.

In petrology, micrographic texture is a fine-grained intergrowth of quartz and alkali feldspar, interpreted as the last product of crystallization in some igneous rocks which contain high or moderately high percentages of silica. Micropegmatite is an outmoded terminology for micrographic texture.

Leucitite or leucite rock is an igneous rock containing leucite. It is scarce, many countries such as England being entirely without them. However, they are of wide distribution, occurring in every quarter of the globe. Taken collectively, they exhibit a considerable variety of types and are of great interest petrographically. For the presence of this mineral it is necessary that the silica percentage of the rock should be low, since leucite is incompatible with free quartz and reacts with it to form potassium feldspar. Because it weathers rapidly, leucite is most common in lavas of recent and Tertiary age, which have a fair amount of potassium, or at any rate have potassium equal to or greater than sodium; if sodium is abundant nepheline occurs rather than leucite.

A petrographic microscope is a type of optical microscope used to identify rocks and minerals in thin sections. The microscope is used in optical mineralogy and petrography, a branch of petrology which focuses on detailed descriptions of rocks. The method includes aspects of polarized light microscopy (PLM).

This glossary of geology is a list of definitions of terms and concepts relevant to geology, its sub-disciplines, and related fields. For other terms related to the Earth sciences, see Glossary of geography terms.