Sonata form is a musical structure generally consisting of three main sections: an exposition, a development, and a recapitulation. It has been used widely since the middle of the 18th century.

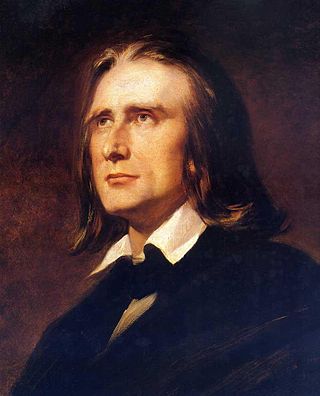

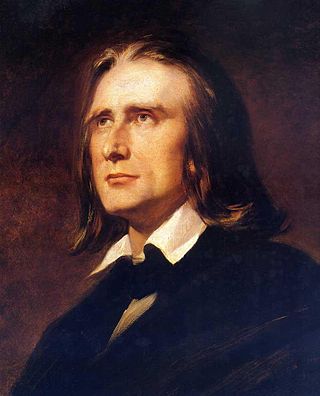

A symphonic poem or tone poem is a piece of orchestral music, usually in a single continuous movement, which illustrates or evokes the content of a poem, short story, novel, painting, landscape, or other (non-musical) source. The German term Tondichtung appears to have been first used by the composer Carl Loewe in 1828. The Hungarian composer Franz Liszt first applied the term Symphonische Dichtung to his 13 works in this vein, which commenced in 1848.

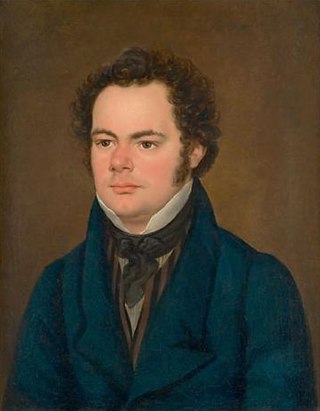

The Piano Quintet in E-flat major, Op. 44, by Robert Schumann was composed in 1842 and received its first public performance the following year. Noted for its "extroverted, exuberant" character, Schumann's piano quintet is considered one of his finest compositions and a major work of nineteenth-century chamber music. Composed for piano and string quartet, the work revolutionized the instrumentation and musical character of the piano quintet and established it as a quintessentially Romantic genre.

Ludwig van Beethoven's Piano Sonata No. 29 in B♭ major, Op. 106 is a piano sonata that is widely viewed as one of the most important works of the composer's third period and among the greatest piano sonatas of all time. Completed in 1818, it is often considered to be Beethoven's most technically challenging piano composition and one of the most demanding solo works in the classical piano repertoire. The first documented public performance was in 1836 by Franz Liszt in the Salle Erard in Paris to an enthusiastic review by Hector Berlioz.

The Piano Concerto No. 5 in E-flat major, Op. 73, known as the Emperor Concerto in English-speaking countries, is a concerto composed by Ludwig van Beethoven for piano and orchestra. Beethoven composed the concerto in 1809 under salary in Vienna, and he dedicated it to Archduke Rudolf, who was his patron, friend, and pupil. Its public premiere was on 28 November 1811 in Leipzig, with Friedrich Schneider as the soloist and Johann Philipp Christian Schulz conducting the Gewandhaus Orchestra. Beethoven, usually the soloist, could not perform due to declining hearing.

Cyclic form is a technique of musical construction, involving multiple sections or movements, in which a theme, melody, or thematic material occurs in more than one movement as a unifying device. Sometimes a theme may occur at the beginning and end ; other times a theme occurs in a different guise in every part.

Sonata form is one of the most influential ideas in the history of Western classical music. Since the establishment of the practice by composers like C.P.E. Bach, Haydn, Mozart, Beethoven, and Schubert and the codification of this practice into teaching and theory, the practice of writing works in sonata form has changed considerably.

The Piano Sonata in B minor, S.178, is a piano sonata by Franz Liszt. It was completed in 1853 and published in 1854 with a dedication to Robert Schumann.

A Faust Symphony in three character pictures, S.108, or simply the "Faust Symphony", is a choral symphony written by Hungarian composer Franz Liszt inspired by Johann Wolfgang von Goethe's drama, Faust. The symphony was premiered in Weimar on 5 September 1857, for the inauguration of the Goethe–Schiller Monument there.

The Piano Concerto No. 2 in B-flat major, Op. 19, by Ludwig van Beethoven was composed primarily between 1787 and 1789, although it did not attain the form in which it was published until 1795. Beethoven did write a second finale for it in 1798 for performance in Prague, but that is not the finale that was published. It was used by the composer as a vehicle for his own performances as a young virtuoso, initially intended with the Bonn Hofkapelle. It was published in December 1801 as Op. 19, later than the publication in March that year of his later composition the Piano Concerto No. 1 in C major as Op. 15, and thus became designated as his second piano concerto.

Franz Liszt composed his Piano Concerto No. 1 in E♭ major, S.124 over a 26-year period; the main themes date from 1830, while the final version is dated 1849. The concerto consists of four movements and lasts approximately 20 minutes. It premiered in Weimar on February 17, 1855, with Liszt at the piano and Hector Berlioz conducting.

The Concerto pathétique (S.258/2), completed in 1866, is Franz Liszt's most substantial and ambitious two-piano work. At least three piano concerto arrangements of the work have been made by other composers, based on Liszt's suggestions.

Après une lecture du Dante: Fantasia quasi Sonata is a piano sonata in one movement, written by Hungarian composer Franz Liszt in 1849. It was first published in 1856 as part of the second volume of his Années de pèlerinage. This work of program music was inspired by the reading of Victor Hugo's poem “Après une lecture de Dante” (1836).

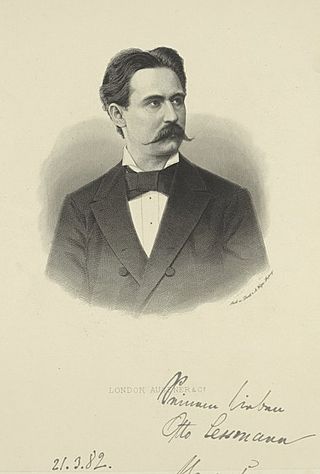

The Sonata on the 94th Psalm in C minor is a sonata for solo organ by Julius Reubke, based on the text of Psalm 94. It is considered one of the pinnacles of the Romantic repertoire.

The symphonic poems of the Hungarian composer Franz Liszt are a series of 13 orchestral works, numbered S.95–107. The first 12 were composed between 1848 and 1858 ; the last, Von der Wiege bis zum Grabe, followed in 1882. These works helped establish the genre of orchestral program music—compositions written to illustrate an extra-musical plan derived from a play, poem, painting or work of nature. They inspired the symphonic poems of Bedřich Smetana, Antonín Dvořák, Richard Strauss and others.

Piano Sonata No. 1 in D minor, Op. 28, is a piano sonata by Sergei Rachmaninoff, completed in 1908. It is the first of three "Dresden pieces", along with the Symphony No. 2 and part of an opera, which were composed in the quiet city of Dresden, Germany. It was originally inspired by Goethe's tragic play Faust; although Rachmaninoff abandoned the idea soon after beginning composition, traces of this influence can still be found. After numerous revisions and substantial cuts made at the advice of his colleagues, he completed it on April 11, 1908. Konstantin Igumnov gave the premiere in Moscow on October 17, 1908. It received a lukewarm response there, and remains one of the least performed of Rachmaninoff's works.

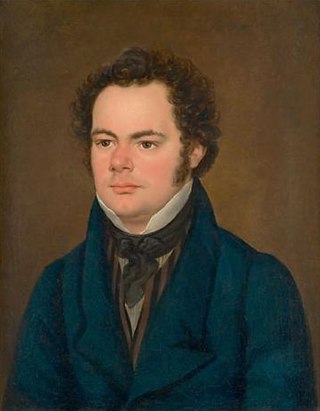

Franz Schubert's last three piano sonatas, D 958, 959 and 960, are his last major compositions for solo piano. They were written during the last months of his life, between the spring and autumn of 1828, but were not published until about ten years after his death, in 1838–39. Like the rest of Schubert's piano sonatas, they were mostly neglected in the 19th century. By the late 20th century, however, public and critical opinion had changed, and these sonatas are now considered among the most important of the composer's mature masterpieces. They are part of the core piano repertoire, appearing regularly on concert programs and recordings.

Thematic transformation is a musical technique in which a leitmotif, or theme, is developed by changing the theme by using permutation, augmentation, diminution, and fragmentation. It was primarily developed by Franz Liszt and Hector Berlioz. The technique is essentially one of variation. A basic theme is reprised throughout a musical work, but it undergoes constant transformations and disguises and is made to appear in several contrasting roles. However, the transformations of this theme will always serve the purpose of "unity within variety" that was the architectural role of sonata form in the classical symphony. The difference here is that thematic transformation can accommodate the dramatically charged phrases, highly coloured melodies and atmospheric harmonies favored by the Romantic composers, whereas sonata form was geared more toward the more objective characteristics of absolute music. Also, while thematic transformation is similar to variation, the effect is usually different since the transformed theme has a life of its own and is no longer a sibling to the original theme.

Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky struggled with sonata form, the primary Western principle for building large-scale musical structures since the middle of the 18th century. Traditional Russian treatment of melody, harmony and structure actually worked against sonata form's modus operandi of movement, growth and development. Russian music—the Russian creative mentality as a whole, in fact—functioned on the principle of stasis. Russian novels, plays and operas were written as collections of self-contained tableaux, with the plots proceeding from one set-piece to the next. Russian folk music operated along the same lines, with songs comprised as a series of self-contained melodic units repeated continually. Compared to this mindset, the precepts of sonata form probably seemed as alien as if they had arrived from the moon.

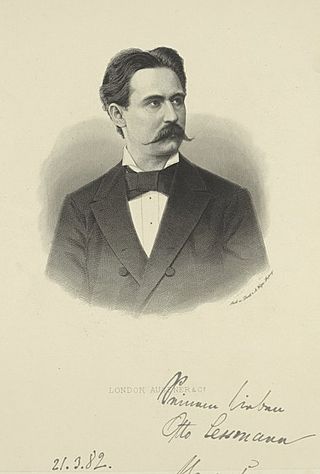

The Piano Concerto No. 1 in B-flat minor, Op. 32, is a work for piano and orchestra completed by Xaver Scharwenka in 1876. The first performance was given on 14 April 1875 by the composer at the piano, under Julius Stern's direction. The work is dedicated to Franz Liszt.