The Crow, whose autonym is Apsáalooke, also spelled Absaroka, are Native Americans living primarily in southern Montana. Today, the Crow people have a federally recognized tribe, the Crow Tribe of Montana, with an Indian reservation, the Crow Indian Reservation, located in the south-central part of the state.

The Arapaho are a Native American people historically living on the plains of Colorado and Wyoming. They were close allies of the Cheyenne tribe and loosely aligned with the Lakota and Dakota.

The Comanche or Nʉmʉnʉʉ is a Native American tribe from the Southern Plains of the present-day United States. Comanche people today belong to the federally recognized Comanche Nation, headquartered in Lawton, Oklahoma.

The Battle of the Little Bighorn, known to the Lakota and other Plains Indians as the Battle of the Greasy Grass, and commonly referred to as Custer's Last Stand, was an armed engagement between combined forces of the Lakota Sioux, Northern Cheyenne, and Arapaho tribes and the 7th Cavalry Regiment of the United States Army. The battle, which resulted in the defeat of U.S. forces, was the most significant action of the Great Sioux War of 1876. It took place on June 25–26, 1876, along the Little Bighorn River in the Crow Indian Reservation in southeastern Montana Territory.

The Cheyenne are an Indigenous people of the Great Plains. Their Cheyenne language belongs to the Algonquian language family. Today, the Cheyenne people are split into two federally recognized nations: the Southern Cheyenne, who are enrolled in the Cheyenne and Arapaho Tribes in Oklahoma, and the Northern Cheyenne, who are enrolled in the Northern Cheyenne Tribe of the Northern Cheyenne Indian Reservation in Montana.

The Blackfoot Confederacy, Niitsitapi, or Siksikaitsitapi, is a historic collective name for linguistically related groups that make up the Blackfoot or Blackfeet people: the Siksika ("Blackfoot"), the Kainai or Blood, and two sections of the Peigan or Piikani – the Northern Piikani (Aapátohsipikáni) and the Southern Piikani. Broader definitions include groups such as the Tsúùtínà (Sarcee) and A'aninin who spoke quite different languages but allied with or joined the Blackfoot Confederacy.

Kiowa or CáuigúIPA:[kɔ́j-gʷú]) people are a Native American tribe and an Indigenous people of the Great Plains of the United States. They migrated southward from western Montana into the Rocky Mountains in Colorado in the 17th and 18th centuries, and eventually into the Southern Plains by the early 19th century. In 1867, the Kiowa were moved to a reservation in southwestern Oklahoma.

Red Cloud's War was an armed conflict between an alliance of the Lakota, Northern Cheyenne, and Northern Arapaho peoples against the United States and the Crow Nation that took place in the Wyoming and Montana territories from 1866 to 1868. The war was fought over control of the western Powder River Country in present north-central Wyoming.

Arikara, also known as Sahnish, Arikaree, Ree, or Hundi, are a tribe of Native Americans in North Dakota. Today, they are enrolled with the Mandan and the Hidatsa as the federally recognized tribe known as the Mandan, Hidatsa, and Arikara Nation.

Plenty Coups was the principal chief of the Crow Tribe and a visionary leader.

Plains Indians or Indigenous peoples of the Great Plains and Canadian Prairies are the Native American tribes and First Nation band governments who have historically lived on the Interior Plains of North America. While hunting-farming cultures have lived on the Great Plains for centuries prior to European contact, the region is known for the horse cultures that flourished from the 17th century through the late 19th century. Their historic nomadism and armed resistance to domination by the government and military forces of Canada and the United States have made the Plains Indian culture groups an archetype in literature and art for Native Americans everywhere.

The Sioux Wars were a series of conflicts between the United States and various subgroups of the Sioux people which occurred in the later half of the 19th century. The earliest conflict came in 1854 when a fight broke out at Fort Laramie in Wyoming, when Sioux warriors killed 31 American soldiers in the Grattan Massacre, and the final came in 1890 during the Ghost Dance War.

Joseph Medicine Crow was a Native American writer, historian and war chief of the Crow Tribe. His writings on Native American history and reservation culture are considered seminal works, but he is best known for his writings and lectures concerning the Battle of the Little Bighorn of 1876.

Among the Plains Indians of North America, counting coup is the warrior tradition of winning prestige against an enemy in battle. It is one of the traditional ways of showing bravery in the face of an enemy and involves intimidating him, and, it is hoped, persuading him to admit defeat, without having to kill him. These victories may then be remembered, recorded, and recounted as part of the community's oral, written, or pictorial histories.

Running Eagle (Pi'tamaka) was a Native American woman and war chief of the Blackfeet Tribe known for her success in battle.

The Battle of Little Robe Creek, also known as the Battle of Antelope Hills and the Battle of the South Canadian, took place on May 12, 1858. It was a series of three distinct encounters that took place on a single day, between the Comanches, with Texas Rangers, militia, and allied Tonkawas attacking them. It was undertaken against the laws of the United States at the time, which strictly forbade such an incursion into the Indian Territories of Oklahoma, and marked a significant escalation of the Indian Wars. It also marked the first time American or Texas Ranger forces had penetrated the Comancheria as far as the Wichita Mountains and Canadian River, and it marked a decisive defeat for the Comanches.

Plains hide painting is a traditional North American Plains Indian artistic practice of painting on either tanned or raw animal hides. Tipis, tipi liners, shields, parfleches, robes, clothing, drums, and winter counts could all be painted.

Flying Hawk, also known as Moses Flying Hawk, was an Oglala Lakota warrior, historian, educator and philosopher. Flying Hawk's life chronicles the history of the Oglala Lakota people through the 19th and early 20th centuries, as he fought to deflect the worst effects of white rule; educate his people and preserve sacred Oglala Lakota land and heritage.

The Crow War, also known as the Crow Rebellion, or the Crow Uprising, was the only armed conflict between the United States and the Crow tribe of Montana, and the last Indian War fought in the state. In September 1887, the young medicine man Wraps-Up-His-Tail, or Sword Bearer, led a small group of warriors in a raid against a group of Blackfoot which had captured horses from the Crow reservation. Following the raid, Sword Bearer led his group back to the Crow Agency to inform the Indian agent of his victory, but an incident arose which ended with the young leader taking his followers into the mountains. In response, the United States Army launched a successful campaign to bring the Crow back to the reservation.

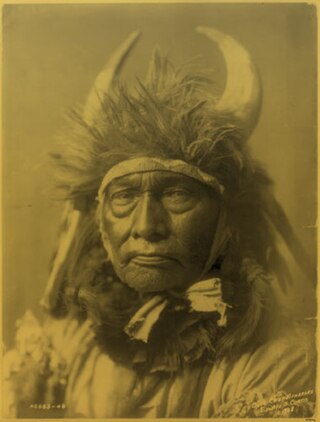

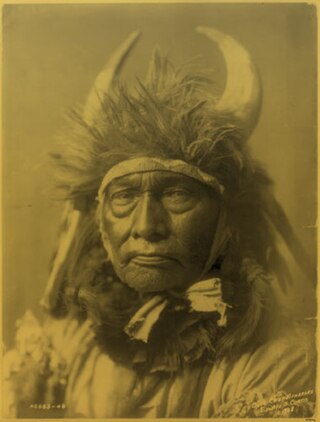

Bull Chief was an Apsaroke (Crow) chief.