A cough is a sudden expulsion of air through the large breathing passages that can help clear them of fluids, irritants, foreign particles and microbes. As a protective reflex, coughing can be repetitive with the cough reflex following three phases: an inhalation, a forced exhalation against a closed glottis, and a violent release of air from the lungs following opening of the glottis, usually accompanied by a distinctive sound.

Hemoptysis is the coughing up of blood or blood-stained mucus from the bronchi, larynx, trachea, or lungs. In other words, it is the airway bleeding. This can occur with lung cancer, infections such as tuberculosis, bronchitis, or pneumonia, and certain cardiovascular conditions. Hemoptysis is considered massive at 300 mL. In such cases, there are always severe injuries. The primary danger comes from choking, rather than blood loss.

Bronchiectasis is a disease in which there is permanent enlargement of parts of the airways of the lung. Symptoms typically include a chronic cough with mucus production. Other symptoms include shortness of breath, coughing up blood, and chest pain. Wheezing and nail clubbing may also occur. Those with the disease often get frequent lung infections.

Pulmonology, pneumology or pneumonology is a medical specialty that deals with diseases involving the respiratory tract. It is also known as respirology, respiratory medicine, or chest medicine in some countries and areas.

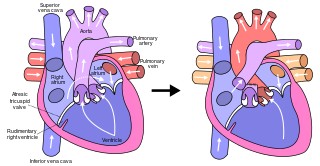

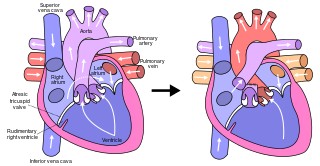

The Fontan procedure or Fontan–Kreutzer procedure is a palliative surgical procedure used in children with univentricular hearts. It involves diverting the venous blood from the inferior vena cava (IVC) and superior vena cava (SVC) to the pulmonary arteries without passing through the morphologic right ventricle; i.e., the systemic and pulmonary circulations are placed in series with the functional single ventricle. The procedure was initially performed in 1968 by Francis Fontan and Eugene Baudet from Bordeaux, France, published in 1971, simultaneously described in 1971 by Guillermo Kreutzer from Buenos Aires, Argentina, and finally published in 1973.

Lymphangioleiomyomatosis (LAM) is a rare, progressive and systemic disease that typically results in cystic lung destruction. It predominantly affects women, especially during childbearing years. The term sporadic LAM is used for patients with LAM not associated with tuberous sclerosis complex (TSC), while TSC-LAM refers to LAM that is associated with TSC.

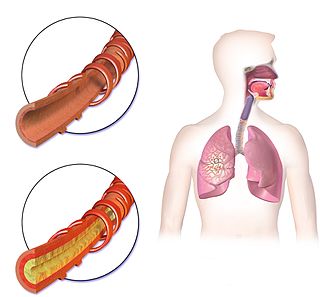

Bronchoconstriction is the constriction of the airways in the lungs due to the tightening of surrounding smooth muscle, with consequent coughing, wheezing, and shortness of breath.

Chest physiotherapy (CPT) are treatments generally performed by physical therapists and respiratory therapists, whereby breathing is improved by the indirect removal of mucus from the breathing passages of a patient. Other terms include respiratory or cardio-thoracic physiotherapy.

Reactive airway disease (RAD) is an informal label that physicians apply to patients with symptoms similar to those of asthma. An exact definition of the condition does not exist. Individuals who are typically labeled as having RAD generally have a history of wheezing, coughing, dyspnea, and production of sputum that may or may not be caused by asthma. Symptoms may also include, but are not limited to, coughing, shortness of breath, excess mucus in the bronchial tube, swollen mucous membrane in the bronchial tube, and/or hypersensitive bronchial tubes. Physicians most commonly label patients with RAD when they are hesitant about formally diagnosing a patient with asthma, which is most prevalent in the pediatric setting. While some physicians may use RAD and asthma synonymously, there is controversy over this usage.

Aspergillosis is a fungal infection of usually the lungs, caused by the genus Aspergillus, a common mould that is breathed in frequently from the air around, but does not usually affect most people. It generally occurs in people with lung diseases such as asthma, cystic fibrosis or tuberculosis, or those who have had a stem cell or organ transplant, and those who cannot fight infection because of medications they take such as steroids and some cancer treatments. Rarely, it can affect skin.

A bronchopulmonary segment is a portion of lung supplied by a specific segmental bronchus and its vessels. These arteries branch from the pulmonary and bronchial arteries, and run together through the center of the segment. Veins and lymphatic vessels drain along the edges of the segment. The segments are separated from each other by layers of connective tissue that forms them into discrete anatomical and functional units. This separation means that a bronchopulmonary segment can be surgically removed without affecting the function of the others.

Bronchorrhea is the production of more than 100 mL per day of watery sputum. Chronic bronchitis is a common cause, but it may also be caused by asthma, pulmonary contusion, bronchiectasis, tuberculosis, cancer, scorpion stings, severe hypothermia and poisoning by organophosphates and other poisons. Massive bronchorrhea may occur in either bronchioloalveolar carcinoma, or in metastatic cancer that is growing in a bronchioloalveolar pattern. It commonly occurs in the setting of chest wall trauma, in which setting it can cause lobar atelectasis.

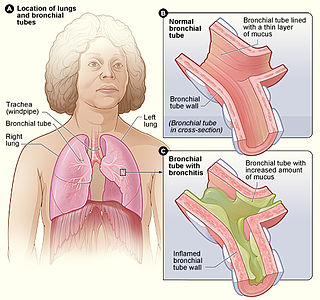

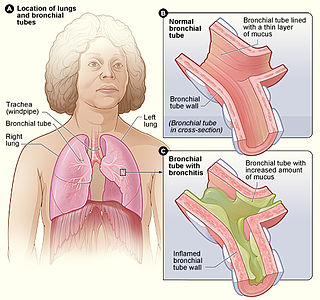

Bronchitis is inflammation of the bronchi in the lungs that causes coughing. Bronchitis usually begins as an infection in your nose, ears, throat, or sinuses. The infection then makes its way down to the bronchi. Symptoms include coughing up sputum, wheezing, shortness of breath, and chest pain. Bronchitis can be acute or chronic.

Williams–Campbell syndrome (WCS) is a disease of the airways where cartilage in the bronchi is defective. It is a form of congenital cystic bronchiectasis. This leads to collapse of the airways and bronchiectasis. It acts as one of the differential to allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis. WCS is a deficiency of the bronchial cartilage distally.

Pulmonary hygiene, formerly referred to as pulmonary toilet, is a set of methods used to clear mucus and secretions from the airways. The word pulmonary refers to the lungs. The word toilet, related to the French toilette, refers to body care and hygiene; this root is used in words such as toiletry that also relate to cleansing.

Eosinophilic bronchitis (EB) is a type of airway inflammation due to excessive mast cell recruitment and activation in the superficial airways as opposed to the smooth muscles of the airways as seen in asthma. It often results in a chronic cough. Lung function tests are usually normal. Inhaled corticosteroids are often an effective treatment.

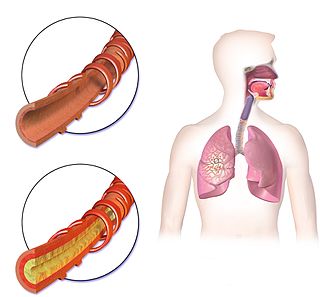

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) is a type of progressive lung disease characterized by long-term respiratory symptoms and airflow limitation. The main symptoms include shortness of breath and a cough, which may or may not produce mucus. COPD progressively worsens, with everyday activities such as walking or dressing becoming difficult. While COPD is incurable, it is preventable and treatable.

Chronic pulmonary aspergillosis is a long-term fungal infection caused by members of the genus Aspergillus—most commonly Aspergillusfumigatus. The term describes several disease presentations with considerable overlap, ranging from an aspergilloma—a clump of Aspergillus mold in the lungs—through to a subacute, invasive form known as chronic necrotizing pulmonary aspergillosis which affects people whose immune system is weakened. Many people affected by chronic pulmonary aspergillosis have an underlying lung disease, most commonly tuberculosis, allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis, asthma, or lung cancer.

A lung cavity or pulmonary cavity is an abnormal, thick-walled, air-filled space within the lung. Cavities in the lung can be caused by infections, cancer, autoimmune conditions, trauma, congenital defects, or pulmonary embolism. The most common cause of a single lung cavity is lung cancer. Bacterial, mycobacterial, and fungal infections are common causes of lung cavities. Globally, tuberculosis is likely the most common infectious cause of lung cavities. Less commonly, parasitic infections can cause cavities. Viral infections almost never cause cavities. The terms cavity and cyst are frequently used interchangeably; however, a cavity is thick walled, while a cyst is thin walled. The distinction is important because cystic lesions are unlikely to be cancer, while cavitary lesions are often caused by cancer.

Bronchial artery embolization is a treatment for hemoptysis, abbreviated as BAE. It is a kind of catheter intervention to control hemoptysis by embolizing the bronchial artery, which is a bleeding source. Embolic agents are particulate embolic material such as gelatin sponge or polyvinyl alcohol (PVA), and liquid embolic material such as NBCA, or metallic coils.