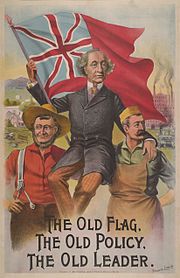

The Reform Party of Canada was a right-wing populist and conservative federal political party in Canada that existed under that name from 1987 to 2000. Reform was founded as a Western Canada-based protest movement that eventually became a populist conservative party, with strong Christian right influence and social conservative elements. It was initially motivated by the perceived need for democratic reforms and by profound Western Canadian discontent with the Progressive Conservative Party.

Ernest Charles Manning, was a Canadian politician and the eighth premier of Alberta between 1943 and 1968 for the Social Credit Party of Alberta. He served longer than any other premier in the province's history and was the second longest-serving provincial premier in Canadian history. Manning's 25 consecutive years as premier were defined by strong social conservatism and fiscal conservatism. He was also the only member of the Social Credit Party of Canada to sit in the Senate and, with the party shut out of the House of Commons in 1980, was its last representative in Parliament when he retired from the Senate in 1983.

William Andrew Cecil Bennett was a Canadian politician. He was the 25th premier of British Columbia from 1952 to 1972. With just over 20 years in office, Bennett was and remains the longest-serving premier in British Columbia history. He was usually referred to as W. A. C. Bennett, although some referred to him either affectionately or mockingly as "Wacky" Bennett. To his close friends, he was known as "Cece".

The British Columbia Social Credit Party, whose members are known as Socreds, was the governing provincial political party of British Columbia, Canada, for all but three years between the 1952 provincial election and the 1991 election. For four decades, the party dominated the British Columbian political scene, with the only break occurring between the 1972 and 1975 elections when the British Columbia New Democratic Party governed.

The Canadian social credit movement is a political movement originally based on the Social Credit theory of Major C. H. Douglas. Its supporters were colloquially known as Socreds in English and créditistes in French. It gained popularity and its own political party in the 1930s, as a result of the Great Depression.

The Politics of Alberta are centred on a provincial government resembling that of the other Canadian provinces, namely a constitutional monarchy and parliamentary democracy. The capital of the province is Edmonton, where the provincial Legislative Building is located.

Alberta Social Credit was a provincial political party in Alberta, Canada, that was founded on social credit monetary policy put forward by Clifford Hugh Douglas and on conservative Christian social values. The Canadian social credit movement was largely an out-growth of Alberta Social Credit. The Social Credit Party of Canada was strongest in Alberta, before developing a base in Quebec when Réal Caouette agreed to merge his Ralliement créditiste movement into the federal party. The British Columbia Social Credit Party formed the government for many years in neighbouring British Columbia, although this was effectively a coalition of centre-right forces in the province that had no interest in social credit monetary policies.

The Social Credit Party of Canada, colloquially known as the Socreds, was a populist political party in Canada that promoted social credit theories of monetary reform. It was the federal wing of the Canadian social credit movement.

Unity, United Progressive Movement and United Reform were the names used in Canada by a popular front party initiated by the Communist Party of Canada in the late 1930s.

The United Farmers of Alberta (UFA) is an association of Alberta farmers that has served different roles in its 100-year history – as a lobby group, a successful political party, and as a farm-supply retail chain. As a political party, it formed the government of Alberta from 1921 to 1935.

David Réal Caouette was a Canadian politician from Quebec. He was a member of Parliament (MP) and leader of the Social Credit Party of Canada and founder of the Ralliement des créditistes. Outside politics he worked as a car dealer.

Robert Norman Thompson was a Canadian politician, chiropractor, and educator. He was born in Duluth, Minnesota, to Canadian parents and moved to Canada in 1918 with his family. Raised in Alberta, he graduated from the Palmer School of Chiropractic in 1939 and worked as a chiropractor and then as a teacher before serving in the Royal Canadian Air Force during World War II.

The 1945 Canadian federal election was held on June 11, 1945, to elect members of the House of Commons of the 20th Parliament of Canada. Prime Minister William Lyon Mackenzie King's Liberal government was re-elected to its third consecutive term, although this time with a minority government as the Liberals fell five seats short of a majority.

The Manitoba Social Credit Party was a political party in the Canadian province of Manitoba. In its early years, it espoused the monetary reform theories of social credit.

The 1935 Alberta general election was held on August 22, 1935, to elect members of the Legislative Assembly of Alberta. The newly founded Social Credit Party of Alberta won a sweeping victory, unseating the 14-year government of the United Farmers of Alberta. It was one of only five times that Alberta has changed governments.

Pierre Marcel Poilievre is a Canadian politician who has served as the leader of the Conservative Party of Canada and the leader of the Official Opposition since 2022. Poilievre has served as a member of Parliament (MP) since 2004.

The 1952 British Columbia general election was the 23rd general election in the Canadian province of British Columbia. It was held to elect members of the Legislative Assembly of British Columbia, alongside a plebiscite on daylight saving time and liquor. The election was called on April 10, 1952, and held on June 12, 1952. The new legislature met for the first time on February 3, 1953.

Right-wing populism, also called national populism and right-wing nationalism, is a political ideology that combines right-wing politics and populist rhetoric and themes. Its rhetoric employs anti-elitist sentiments, opposition to the Establishment, and speaking to or for the "common people". Recurring themes of right-wing populists include neo-nationalism, social conservatism, economic nationalism and fiscal conservatism. Frequently, they aim to defend a national culture, identity, and economy against perceived attacks by outsiders.

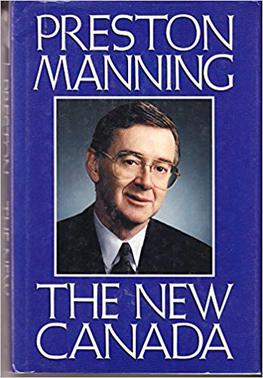

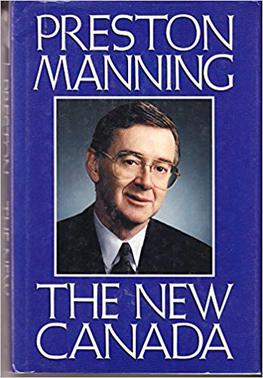

The New Canada is a Canadian political literature book written by Reform Party of Canada founder and leader Preston Manning and published by Macmillan Canada. The book explains the personal, religious, and political life of Preston Manning and explains the roots and beliefs of the Reform Party. At the time of its publishing in 1991, Reform had become a popular populist conservative party in Western Canada after the mainstream Progressive Conservative Party of Canada was collapsing in support and in 1991 decided to expand eastward into Ontario and the Maritime provinces. One year later the PC party collapsed in the 1993 federal election, allowing the Reform Party to make political history in Canada, displacing the PCs as the dominant conservative party in Canada. Reform, later renamed the Canadian Alliance, merged with the PC Party in 2003, to form a united right-wing alternative to the governing Liberal Party of Canada, named the Conservative Party of Canada which has dropped many of the populist themes that the Reform Party had.