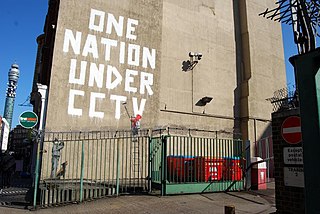

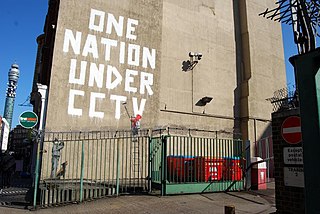

Privacy is the ability of an individual or group to seclude themselves or information about themselves, and thereby express themselves selectively.

The Uniform Anatomical Gift Act (UAGA), and its periodic revisions, is one of the Uniform Acts drafted by the National Conference of Commissioners on Uniform State Laws (NCCUSL), also known as the Uniform Law Commission (ULC), in the United States with the intention of harmonizing state laws between the states.

Personality rights, sometimes referred to as the right of publicity, are rights for an individual to control the commercial use of their identity, such as name, image, likeness, or other unequivocal identifiers. They are generally considered as property rights, rather than personal rights, and so the validity of personality rights of publicity may survive the death of the individual to varying degrees, depending on the jurisdiction.

An autopsy is a surgical procedure that consists of a thorough examination of a corpse by dissection to determine the cause, mode, and manner of death; or the exam may be performed to evaluate any disease or injury that may be present for research or educational purposes. The term necropsy is generally used for non-human animals.

Medical privacy, or health privacy, is the practice of maintaining the security and confidentiality of patient records. It involves both the conversational discretion of health care providers and the security of medical records. The terms can also refer to the physical privacy of patients from other patients and providers while in a medical facility, and to modesty in medical settings. Modern concerns include the degree of disclosure to insurance companies, employers, and other third parties. The advent of electronic medical records (EMR) and patient care management systems (PCMS) have raised new concerns about privacy, balanced with efforts to reduce duplication of services and medical errors.

In common law jurisdictions, probate is the judicial process whereby a will is "proved" in a court of law and accepted as a valid public document that is the true last testament of the deceased, or whereby the estate is settled according to the laws of intestacy in the state of residence of the deceased at time of death in the absence of a legal will.

Privacy laws of the United States deal with several different legal concepts. One is the invasion of privacy, a tort based in common law allowing an aggrieved party to bring a lawsuit against an individual who unlawfully intrudes into their private affairs, discloses their private information, publicizes them in a false light, or appropriates their name for personal gain.

Information privacy, data privacy or data protection laws provide a legal framework on how to obtain, use and store data of natural persons. The various laws around the world describe the rights of natural persons to control who is using its data. This includes usually the right to get details on which data is stored, for what purpose and to request the deletion in case the purpose is not given anymore.

Privacy law is the body of law that deals with the regulating, storing, and using of personally identifiable information, personal healthcare information, and financial information of individuals, which can be collected by governments, public or private organisations, or other individuals. It also applies in the commercial sector to things like trade secrets and the liability that directors, officers, and employees have when handling sensitive information.

The Celebrities Rights Act or Celebrity Rights Act was passed in California in 1985, which enabled a celebrity's personality rights to survive his or her death. Previously, the 1979 Lugosi v. Universal Pictures decision by the California Supreme Court held that Bela Lugosi's personality rights could not pass to his heirs, as a copyright would have. The court ruled that any rights of publicity, and rights to his image, terminated with Lugosi's death.

Information technology law(IT law) or information, communication and technology law (ICT law) (also called cyberlaw) concerns the juridical regulation of information technology, its possibilities and the consequences of its use, including computing, software coding, artificial intelligence, the internet and virtual worlds. The ICT field of law comprises elements of various branches of law, originating under various acts or statutes of parliaments, the common and continental law and international law. Some important areas it covers are information and data, communication, and information technology, both software and hardware and technical communications technology, including coding and protocols.

Digital inheritance is the passing down of digital assets to designated beneficiaries after a person’s death as part of the estate of the deceased. The process includes understanding what digital assets exist and navigating the rights for heirs to access and use those digital assets after a person has died.

The Unified Victim Identification System (UVIS) is an Internet-enabled database system developed for the Office of Chief Medical Examiner of the City of New York (OCME) in the aftermath of the September 11 attacks on New York City and the crash of American Airlines Flight 587. It is intended to handle critical fatality management functions made necessary by a major disaster. UVIS is a strong flexible role-based application and permissions can be controlled dynamically.

A recent extension to the cultural relationship with death is the increasing number of people who die having created a large amount of digital content, such as social media profiles, that will remain after death. This may result in concern and confusion, because of automated features of dormant accounts, uncertainty of the deceased's preferences that profiles be deleted or left as a memorial, and whether information that may violate the deceased's privacy should be made accessible to family.

Do Not Track legislation protects Internet users' right to choose whether or not they want to be tracked by third-party websites. It has been called the online version of "Do Not Call". This type of legislation is supported by privacy advocates and opposed by advertisers and services that use tracking information to personalize web content. Do Not Track (DNT) is a formerly official HTTP header field, designed to allow internet users to opt-out of tracking by websites—which includes the collection of data regarding a user's activity across multiple distinct contexts, and the retention, use, or sharing of that data outside its context. Efforts to standardize Do Not Track by the World Wide Web Consortium did not reach their goal and ended in September 2018 due to insufficient deployment and support.

The General Data Protection Regulation is a European Union regulation on information privacy in the European Union (EU) and the European Economic Area (EEA). The GDPR is an important component of EU privacy law and human rights law, in particular Article 8(1) of the Charter of Fundamental Rights of the European Union. It also governs the transfer of personal data outside the EU and EEA. The GDPR's goals are to enhance individuals' control and rights over their personal information and to simplify the regulations for international business. It supersedes the Data Protection Directive 95/46/EC and, among other things, simplifies the terminology.

Privacy in education refers to the broad area of ideologies, practices, and legislation that involve the privacy rights of individuals in the education system. Concepts that are commonly associated with privacy in education include the expectation of privacy, the Family Educational Rights and Privacy Act (FERPA), the Fourth Amendment, and the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act of 1996 (HIPAA). Most privacy in education concerns relate to the protection of student data and the privacy of medical records. Many scholars are engaging in an academic discussion that covers the scope of students’ privacy rights, from student in K-12 and even higher education, and the management of student data in an age of rapid access and dissemination of information.

Privacy and the United States government consists of enacted legislation, funding of regulatory agencies, enforcement of court precedents, creation of congressional committees, evaluation of judicial decisions, and implementation of executive orders in response to major court cases and technological change. Because the United States government is composed of three distinct branches governed by both the separation of powers and checks and balances, the change in privacy practice can be separated relative to the actions performed by the three branches.

Celebrity privacy refers to the right of celebrities and public figures, largely entertainers, athletes or politicians, to withhold the information they are unwilling to disclose. This term often pertains explicitly to personal information, which includes addresses and family members, among other data for personal identification. Different from the privacy of the general public, 'Celebrity Privacy' is considered as "controlled publicity," challenged by the press and the fans. In addition, Paparazzi make commercial use of their private data.

Digital cloning is an emerging technology, that involves deep-learning algorithms, which allows one to manipulate currently existing audio, photos, and videos that are hyper-realistic. One of the impacts of such technology is that hyper-realistic videos and photos makes it difficult for the human eye to distinguish what is real and what is fake. Furthermore, with various companies making such technologies available to the public, they can bring various benefits as well as potential legal and ethical concerns.