Related Research Articles

A statute of frauds is a form of statute requiring that certain kinds of contracts be memorialized in writing, signed by the party against whom they are to be enforced, with sufficient content to evidence the contract.

Consideration is the central concept in the common law of contracts and is required, in most cases, for a contract to be enforceable. Consideration is the price one pays for another's promise. It can take a number of forms: money, property, a promise, the doing of an act, or even refraining from doing an act. In broad terms, if one agrees to do something he was not otherwise legally obligated to do, it may be said that he has given consideration. For example, Jack agrees to sell his car to Jill for $100. Jill's payment of $100 is the consideration for Jack's promise to give Jill the car, and Jack's promise to give Jill the car is consideration for Jill's payment of $100.

Consideration is an English common law concept within the law of contract, and is a necessity for simple contracts. The concept of consideration has been adopted by other common law jurisdictions, including the US.

Foakes v Beer[1884] UKHL 1 is an English contract law case, which applied the controversial pre-existing duty rule in the context of part payments of debts. It is a leading case from the House of Lords on the legal concept of consideration. It established the rule that prevents parties from discharging an obligation by part performance, affirming Pinnel's Case (1602) 5 Co Rep 117a. In that case it was said that "payment of a lesser sum on the day [i.e., on or after the due date of a money debt] cannot be any satisfaction of the whole."

Assignment is a legal term used in the context of the laws of contract and of property. In both instances, assignment is the process whereby a person, the assignor, transfers rights or benefits to another, the assignee. An assignment may not transfer a duty, burden or detriment without the express agreement of the assignee. The right or benefit being assigned may be a gift or it may be paid for with a contractual consideration such as money.

Estoppel in English law is a doctrine that may be used in certain situations to prevent a person from relying upon certain rights, or upon a set of facts which is different from an earlier set of facts.

In the law of contracts, the mirror image rule, also referred to as an unequivocal and absolute acceptance requirement, states that an offer must be accepted exactly with no modifications. The offeror is the master of their own offer. An attempt to accept the offer on different terms instead creates a counter-offer, and this constitutes a rejection of the original offer.

Balfour v Balfour [1919] 2 KB 571 is a leading English contract law case. It held that there is a rebuttable presumption against an intention to create a legally enforceable agreement when the agreement is domestic in nature.

Consideration is a concept of English common law and is a necessity for simple contracts but not for special contracts. The concept has been adopted by other common law jurisdictions.

English contract law is the body of law that regulates legally binding agreements in England and Wales. With its roots in the lex mercatoria and the activism of the judiciary during the industrial revolution, it shares a heritage with countries across the Commonwealth, from membership in the European Union, continuing membership in Unidroit, and to a lesser extent the United States. Any agreement that is enforceable in court is a contract. A contract is a voluntary obligation, contrasting to the duty to not violate others rights in tort or unjust enrichment. English law places a high value on ensuring people have truly consented to the deals that bind them in court, so long as they comply with statutory and human rights.

Williams v Roffey Bros & Nicholls (Contractors) Ltd[1989] EWCA Civ 5 is a leading English contract law case. It decided that in varying a contract, a promise to perform a pre-existing contractual obligation will constitute good consideration so long as a benefit is conferred upon the 'promiseor'. This was a departure from the previously established principle that promises to perform pre-existing contractual obligations could not be good consideration.

Contract law regulates the obligations established by agreement, whether express or implied, between private parties in the United States. The law of contracts varies from state to state; there is nationwide federal contract law in certain areas, such as contracts entered into pursuant to Federal Reclamation Law.

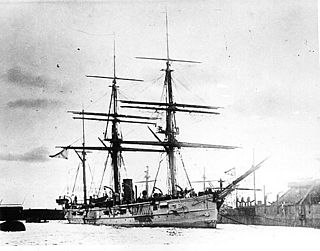

Stilk v Myrick [1809] EWHC KB J58 is an English contract law case heard in the King's Bench on the subject of consideration. In his verdict, the judge, Lord Ellenborough decided that in cases where an individual was bound to do a duty under an existing contract, that duty could not be considered valid consideration for a new contract. It has been distinguished from Williams v Roffey Bros & Nicholls (Contractors) Ltd, which suggested that situations formerly handled by consideration could instead be handled by the doctrine of economic duress.

Unconscionability in English law is a field of contract law and the law of trusts, which precludes the enforcement of voluntary obligations unfairly exploiting the unequal power of the consenting parties. "Inequality of bargaining power" is another term used to express essentially the same idea for the same area of law, which can in turn be further broken down into cases on duress, undue influence and exploitation of weakness. In these cases, where someone's consent to a bargain was only procured through duress, out of undue influence or under severe external pressure that another person exploited, courts have felt it was unconscionable to enforce agreements. Any transfers of goods or money may be claimed back in restitution on the basis of unjust enrichment subject to certain defences.

Intention to create legal relations, otherwise an "intention to be legally bound", is a doctrine used in contract law, particularly English contract law and related common law jurisdictions.

Privity is a doctrine in English contract law that covers the relationship between parties to a contract and other parties or agents. At its most basic level, the rule is that a contract can neither give rights to, nor impose obligations on, anyone who is not a party to the original agreement, i.e. a "third party". Historically, third parties could enforce the terms of a contract, as evidenced in Provender v Wood, but the law changed in a series of cases in the 19th and early 20th centuries, the most well known of which are Tweddle v Atkinson in 1861 and Dunlop Pneumatic Tyre v Selfridge and Co Ltd in 1915.

Angel v. Murray, 113 R.I. 482, 322 A.2d 630 (1974), was a case decided by the Rhode Island Supreme Court that first accepted the rule articulated in the Uniform Commercial Code §2-209(1) and the Restatement Second of Contracts §89(a) that the modification of a contract does not require its own consideration if the modification was made in good faith and was voluntarily accepted by both parties.

Collier v P & MJ Wright (Holdings) Ltd[2007] EWCA Civ 1329 is an English contract law case, concerning the doctrine of consideration and promissory estoppel in relation to "alteration promises".

Glasbrook Brothers Ltd. v Glamorgan County Council [1924] UKHL 3 is an English contract law and labour law case concerning the liability of private parties paying for extra police protection.

Rock Advertising Ltd v MWB Business Exchange Centres Ltd[2018] UKSC 24 is a judicial decision of the Supreme Court of the United Kingdom relating to contract law, concerning consideration and estoppel. Specifically it concerned the effectiveness of "no oral variation" clauses, which provide that any amendments or waiver in relation to the contract must be in writing.

References

- ↑ Wigan v Edwards(1973) 1 ALR 497; 47 ALJR 586. See also Walker, Janet N. (1974). "Wigan v Edwards". Melbourne University Law Review. (1974) 9(3) Melbourne University Law Review 537.

- ↑ Currie v Misa (1875) LR 10 Ex 893

- ↑ Stilk v Myrick (1809) 2 Camp 317

- ↑ Hartley v Ponsonby (1857) 7 E&B 872

- ↑ Glasbrook Bros v Glamorgan CC [1925] AC 270

- ↑ This is the public policy of the courts, i.e what the court considers a "good thing" or a "bad thing"

- ↑ Collins v Godefroy (1831) 1 B& Ad. 950

- ↑ England v Davidson (1840)11 A7E 856

- ↑ Williams v Williams [1957] 1 WLR 148

- ↑ Collins v Godefroy

- ↑ England v Davidson

- ↑ Being estranged and separated, the wife now had a legal duty NOT to charge any expenditure to her husband's account.

- ↑ Ward v Byham [1956]1 WLR 496 Court of Appeal

- ↑ The court added that the mother had gone beyond her existing duty, but there is little evidence of that.

- ↑ Williams v Roffey[1990] 2 WLR 1153

- ↑ The moral of this case is that a contractor should not automatically award a subcontract to the lowest tender; he should have an idea of what a realistic tender should be.

- ↑ Williams v Roffey was severely criticised in Re Selectmove [1993] 1 WLR 474

- ↑ D&C Builders v Rees [1966] CA 2 QB 617

- ↑ Williams v Roffey[1990] 2 WLR 1153

- ↑ But see England v Davidson , which says the opposite.

- ↑ Contracts: Cases and Commentaries: Boyle and Percy

- ↑ UCC

- ↑ UCC

- ↑ UCC

- ↑ Ayres, I. & Speidel, R.E. Studies in Contract Law, Seventh Edition. Foundation Press, New York: 2008, p. 88

- ↑ Ayres, p. 81

- ↑ Admiralty Law - Aleka Mandaraka Sheppard

- ↑ The San Demetrio 69 LLR 5

- ↑ The Beaver (1800) 3 Ch R 92

- Rest. 2nd of Contracts, Section 73.

- UCC Section 2-209(1).