Related Research Articles

In United States law, an Alford plea, also called a Kennedy plea in West Virginia, an Alford guilty plea, and the Alford doctrine, is a guilty plea in criminal court, whereby a defendant in a criminal case does not admit to the criminal act and asserts innocence, even if the evidence presented by the prosecution would be likely to persuade a judge or jury to find the defendant guilty beyond a reasonable doubt. This can be caused by circumstantial evidence and testimony favoring the prosecution and difficulty finding evidence and witnesses that would aid the defense.

A plea bargain is an agreement in criminal law proceedings, whereby the prosecutor provides a concession to the defendant in exchange for a plea of guilt or nolo contendere. This may mean that the defendant will plead guilty to a less serious charge, or to one of the several charges, in return for the dismissal of other charges; or it may mean that the defendant will plead guilty to the original criminal charge in return for a more lenient sentence.

Criminal procedure is the adjudication process of the criminal law. While criminal procedure differs dramatically by jurisdiction, the process generally begins with a formal criminal charge with the person on trial either being free on bail or incarcerated, and results in the conviction or acquittal of the defendant. Criminal procedure can be either in form of inquisitorial or adversarial criminal procedure.

In a legal dispute, one party has the burden of proof to show that they are correct, while the other party has no such burden and is presumed to be correct. The burden of proof requires a party to produce evidence to establish the truth of facts needed to satisfy all the required legal elements of the dispute.

An inquisitorial system is a legal system in which the court, or a part of the court, is actively involved in investigating the facts of the case. This is distinct from an adversarial system, in which the role of the court is primarily that of an impartial referee between the prosecution and the defense.

The presumption of innocence is a legal principle that every person accused of any crime is considered innocent until proven guilty. Under the presumption of innocence, the legal burden of proof is thus on the prosecution, which must present compelling evidence to the trier of fact. If the prosecution does not prove the charges true, then the person is acquitted of the charges. The prosecution must in most cases prove that the accused is guilty beyond a reasonable doubt. If reasonable doubt remains, the accused must be acquitted. The opposite system is a presumption of guilt.

In law, a verdict is the formal finding of fact made by a jury on matters or questions submitted to the jury by a judge. In a bench trial, the judge's decision near the end of the trial is simply referred to as a finding. In England and Wales, a coroner's findings used to be called verdicts but are, since 2009, called conclusions.

Coffin v. United States, 156 U.S. 432 (1895), was an appellate case before the United States Supreme Court in 1895 which established the presumption of innocence of persons accused of crimes.

Not proven is a verdict available to a court of law in Scotland. Under Scots law, a criminal trial may end in one of three verdicts, one of conviction ("guilty") and two of acquittal.

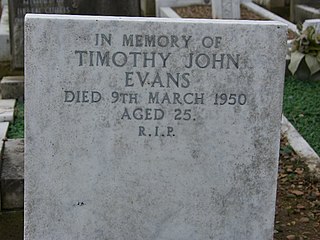

A miscarriage of justice occurs when an unfair outcome occurs in a criminal or civil proceeding, such as the conviction and punishment of a person for a crime they did not commit. Miscarriages are also known as wrongful convictions. Innocent people have sometimes ended up in prison for years before their conviction has eventually been overturned. They may be exonerated if new evidence comes to light or it is determined that the police or prosecutor committed some kind of misconduct at the original trial. In some jurisdictions this leads to the payment of compensation.

In law, a presumption is an "inference of a particular fact". There are two types of presumptions: rebuttable presumptions and irrebuttable presumptions. A rebuttable presumption will either shift the burden of production or the burden of proof ; in short, a fact finder can reject a rebuttable presumption based on other evidence. Conversely, a conclusive/irrebuttable presumption cannot be challenged by contradictory facts or evidence. Sometimes, a presumption must be triggered by a predicate fact—that is, the fact must be found before the presumption applies.

Beyond (a) reasonable doubt is a legal standard of proof required to validate a criminal conviction in most adversarial legal systems. It is a higher standard of proof than the standard of balance of probabilities commonly used in civil cases because the stakes are much higher in a criminal case: a person found guilty can be deprived of liberty, or in extreme cases, life, as well as suffering the collateral consequences and social stigma attached to a conviction. The prosecution is tasked with providing evidence that establishes guilt beyond a reasonable doubt in order to get a conviction; albeit prosecution may fail to complete such task, the trier-of-fact's acceptance that guilt has been proven beyond a reasonable doubt will in theory lead to conviction of the defendant. A failure for the trier-of-fact to accept that the standard of proof of guilt beyond a reasonable doubt has been met thus entitles the accused to an acquittal. This standard of proof is widely accepted in many criminal justice systems, and its origin can be traced to Blackstone's ratio, "It is better that ten guilty persons escape than that one innocent suffer."

Within the criminal justice system of Japan, there exist three basic features that characterize its operations. First, the institutions—police, government prosecutors' offices, courts, and correctional organs—maintain close and cooperative relations with each other, consulting frequently on how best to accomplish the shared goals of limiting and controlling crime. Second, citizens are encouraged to assist in maintaining public order, and they participate extensively in crime prevention campaigns, apprehension of suspects, and offender rehabilitation programs. Finally, officials who administer criminal justice are allowed considerable discretion in dealing with offenders.

A false confession is an admission of guilt for a crime which the individual did not commit. Although such confessions seem counterintuitive, they can be made voluntarily, perhaps to protect a third party, or induced through coercive interrogation techniques. When some degree of coercion is involved, studies have found that subjects with highly sophisticated intelligence or manipulated by their so-called "friends" are more likely to make such confessions. Young people are particularly vulnerable to confessing, especially when stressed, tired, or traumatized, and have a significantly higher rate of false confessions than adults. Hundreds of innocent people have been convicted, imprisoned, and sometimes sentenced to death after confessing to crimes they did not commit—but years later, have been exonerated. It was not until several shocking false confession cases were publicized in the late 1980s, combined with the introduction of DNA evidence, that the extent of wrongful convictions began to emerge—and how often false confessions played a role in these.

Actual innocence is a special standard of review in legal cases to prove that a charged defendant did not commit the crimes that they were accused of, which is often applied by appellate courts to prevent a miscarriage of justice.

Pre-trial detention, also known as jail, preventive detention, provisional detention, or remand, is the process of detaining a person until their trial after they have been arrested and charged with an offence. A person who is on remand is held in a prison or detention centre or held under house arrest. Varying terminology is used, but "remand" is generally used in common law jurisdictions and "preventive detention" elsewhere. However, in the United States, "remand" is rare except in official documents and "jail" is instead the main terminology. Detention before charge is commonly referred to as custody and continued detention after conviction is referred to as imprisonment.

Scots criminal law relies far more heavily on common law than in England and Wales. Scottish criminal law includes offences against the person of murder, culpable homicide, rape and assault, offences against property such as theft and malicious mischief, and public order offences including mobbing and breach of the peace. Scottish criminal law can also be found in the statutes of the UK Parliament with some areas of criminal law, such as misuse of drugs and traffic offences appearing identical on both sides of the Border. Scottish criminal law can also be found in the statute books of the Scottish Parliament such as the Sexual Offences (Scotland) Act 2009 and Prostitution (Scotland) Act 2007 which only apply to Scotland. In fact, the Scots requirement of corroboration in criminal matters changes the practical prosecution of crimes derived from the same enactment. Corroboration is not required in England or in civil cases in Scotland. Scots law is one of the few legal systems that require corroboration.

Following the common law system introduced into Hong Kong when it became a Crown colony, Hong Kong's criminal procedural law and the underlying principles are very similar to the one in the UK. Like other common law jurisdictions, Hong Kong follows the principle of presumption of innocence. This principle penetrates the whole system of Hong Kong's criminal procedure and criminal law. Viscount Sankey once described this principle as a 'golden thread'. Therefore, knowing this principle is vital for understanding the criminal procedures practised in Hong Kong.

In New Zealand, the presumption of supply is a rebuttable presumption in criminal law which is governed by the New Zealand Misuse of Drugs Act 1975. It provides an assumption in drug-possession cases that if a person is found with more than a specified amount of a controlled drug, they are in possession of it for the purpose of supply or sale. This shifts the burden of proof from the Crown to the person found with the drug, who must prove that they possessed it for personal use and not for supply. Note that once the burden of proof has shifted, the burden is one on the balance of probabilities. This presumption exists to make prosecution for supplying drugs easier.

Halliburton Co. v. Erica P. John Fund, Inc., 573 U.S. 258 (2014), is a United States Supreme Court case regarding class action certification for a securities fraud claim. Under the fraud-on-the-market theory, the Court had to inquire as to if markets are economically efficient. The Court presumed they are.

References

- ↑ Raj Bhala. Modern GATT Law: A Treatise on the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade. Sweet & Maxwell. 2005. Page 935.

- ↑ Roscoe, H.; Granger, T.C.; Sharswood, G. (1852). A Digest of the Law of Evidence in Criminal Cases. T. & J.W. Johnson. Retrieved 11 March 2020.

- ↑ This is how presumptions have traditionally been classified: Zuckerman, The Principles of Criminal Evidence, 1989, pp 112 to 115. An irrebuttable presumption of guilt is unconstitutional in the United States: Florida Businessmen for Free Enterprise v. State of Fla. See United States Code Annotated. An example of a rebuttable presumption of guilt is (1983) 301 SE 2d 984. "The presumption of guilt arising from the flight of the accused is a presumption of fact": Hickory v United States (1896) 160 United States Reports 408 (headnote published 1899).

- ↑ Ralph A Newman (ed). Equity in the World's Legal Systems. Établissements Émile Bruylant. 1973. p 559.

- 1 2 Packer, Herbert L. (November 1964). "Two Models of the Criminal Process". University of Pennsylvania Law Review. Pennsylvania: University of Pennsylvania. 113 (1): 1–68. doi:10.2307/3310562. JSTOR 3310562. Archived from the original on 27 April 2019. Retrieved 7 May 2019.

- ↑ Wigmore, John Henry (1905). A Treatise on the System of Evidence in Trials at Common Law. Vol. 4. Boston: Little, Brown and Company. p. 3562, Note 1 to section 2513 – via Internet Archive.

- ↑ Director of Public Prosecutions v. Labavarde and Anor. (1965) 44 International Law Reports 104 at 106; Mauritius Reports, 1965 72 at 74, Mauritius, High Court

- ↑ Lauterpacht, E. (1972). International Law Reports. International Law Reports 160 Volume Hardback Set. Cambridge University Press. p. 104. ISBN 978-0-521-46389-8 . Retrieved 11 March 2020.

- ↑ For example, Scottish International, vols 6 to 7, p 146

- ↑ Dammer and Albanese. Comparative Criminal Justice Systems. Wadsworth. 2014. p 128.

- ↑ Roberts and Redmayne. Innovations in Evidence and Proof: Integrating Theory, Research and Teaching. Hart Publishing. Oxford and Portland, Oregon. 2007. p 379.

- ↑ For the origins of this belief in South Africa, see (1970) 87 South African Law Journal 413

- ↑ Ingraham, Barton L. (1996). "The Right of Silence, the Presumption of Innocence, the Burden of Proof, and a Modest Proposal". Journal of Criminal Law & Criminology. 86 (2): 559. doi:10.2307/1144036. JSTOR 1144036 . Retrieved 31 August 2021.

- ↑ Roscoe, H.; Granger, T.C. (1840). A Digest of the Law of Evidence in Criminal Cases. p. 13. Retrieved 11 March 2020.

- ↑ "5. The Presumption of Guilt" (1973) 82 Yale Law Journal 312; "The Skeleton of Plea Bargaing" (1992) 142 New Law Journal 1373; (1995) 14 UCLA Pacific Basin Law Journal 129 & 130; (1986) 77 Journal of Criminal Law & Criminology 950; Stumpf, American Judicial Politics, Prentice Hall, 1998, pp 305 & 328; Rhodes, Plea Bargaining: Who Gains? Who Loses?, Institute for Law and Social Research, 1978, p 9.

- ↑ Lewis, John; Stevenson, Bryan (1 January 2014). "On the Presumption of Guilt". American Bar.

- ↑ Green and Heilbrun, Wrightsman's Psychology and the Legal System, 8th Ed, Wadsworth, 2014, p 169; Roesch and Zapf and Hart, Forensic Psychology and Law, Wiley, 2010, p 158, Kocsis (ed), Applied Criminal Psychology, Charles C Thomas, 2009, p 200; Michael Marshall, "Police Presumption of Guilt Key in False Confessions" Archived 6 August 2020 at the Wayback Machine . 12 November 2002. University of Virginia School of Law.

- 1 2 3 4 Findley, Keith (19 January 2016). "Opinion | The presumption of innocence exists in theory, not reality" . Washington Post. Archived from the original on 18 August 2019. Retrieved 11 March 2020.

- ↑ "Preventive Detention: Prevention of Human Rights" (1991) 2 Yale Journal of Law and Liberation 29 at 31; Selected Decisions of the Human Rights Committee under the Optional Protocol, United Nations, 2007, vol 8, p 347 [ permanent dead link ]

- ↑ New York Review, 'How internment became legal' Archived 8 October 2019 at the Wayback Machine , John Townsend Rich, 22/6/2017

- ↑ Goodman, Emily Jane (7 October 2010). "With Parking Tickets, New Yorkers Are Guilty Until Proven Innocent". Gotham Gazette. Archived from the original on 21 November 2017. Retrieved 11 March 2020.

- ↑ Florida Businessmen for Free Enterprise v. State of Fla (1980) 499 F.Supp. 346. See United States Code Annotated.

- ↑ Roberts, Anna (23 April 2018). "Arrests As Guilt". SSRN 3167521.

- ↑ Hirano, Keiji (13 October 2005). "Justice system flawed by presumed guilt". Japan Times Online. Archived from the original on 21 December 2014. Retrieved 10 March 2020.

- ↑ Kingston, Jeff (8 January 2020). "The Carlos Ghosn case shines a light into the dark corners of Japanese justice". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 29 February 2020. Retrieved 10 March 2020.

- ↑ Adelstein, Jake; Salmon, Andrew (13 January 2020). "'Guilty until proven guilty' in Japan and Korea". Asia Times. Archived from the original on 5 March 2020. Retrieved 10 March 2020.

"If he's clean as he says he is, then he should fairly and squarely prove his innocence in the court of law."

- ↑ Marco Giannangeli, "Police must stop training 'Presumption of Guilt', says High Court judge" Archived 7 February 2018 at the Wayback Machine , Daily Express, 24 December 2017. Accessed 6 February 2018.

- ↑ "Former High Court judge warns calling complainants 'victims' creates presumption of guilt", Scottish Legal News, 6 August 2019

- ↑ DiCanio, M. The encyclopedia of violence: origins, attitudes, consequences. New York: Facts on File, 1993. ISBN 978-0-8160-2332-5.

- ↑ Lisak, David; Gardinier, Lori; Nicksa, Sarah C.; Cote, Ashley M. (2010). "False Allegations of Sexual Assault: An Analysis of Ten Years of Reported Cases". Violence Against Women. 16 (12): 1318–1334. doi:10.1177/1077801210387747. PMID 21164210. S2CID 15377916. Archived from the original on 15 March 2017. Retrieved 7 February 2018.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - ↑ Brendan O'Neill, "Whatever Happened to the Presumption of Innocence?" Archived 7 February 2018 at the Wayback Machine , Los Angeles Times, 16 November 2017. Accessed 6 February 2018.

- 1 2 Stevenson, Bryan (24 June 2017). "A Presumption of Guilt". The New York Review of Books. Archived from the original on 12 December 2019. Retrieved 5 March 2020.

- ↑ "SHEPPARD v. MAXWELL (1966), No. 490, Argued: February 28, 1966 Decided: June 6, 1966". FindLaw's United States Supreme Court. Archived from the original on 6 December 2019. Retrieved 30 November 2019.

- ↑ "Cognitive Bias and Its Impact on Expert Witnesses and the Court". Archived from the original on 23 December 2019. Retrieved 23 December 2019.