Related Research Articles

Flagellation, flogging or whipping is the act of beating the human body with special implements such as whips, rods, switches, the cat o' nine tails, the sjambok, the knout, etc. Typically, flogging has been imposed on an unwilling subject as a punishment; however, it can also be submitted to willingly and even done by oneself in sadomasochistic or religious contexts.

Osroene or Osrhoene was an ancient region and state in Upper Mesopotamia. The Kingdom of Osroene, also known as the "Kingdom of Edessa", according to the name of its capital city, existed from the 2nd century BC, up to the 3rd century AD, and was ruled by the Abgarid dynasty. Generally allied with the Parthians, the Kingdom of Osroene enjoyed semi-autonomy to complete independence from the years of 132 BC to AD 214. Though ruled by a dynasty of Arab origin, the kingdom's population was of mixed culture, being Syriac-speaking from the earliest times. The city's cultural setting was fundamentally Syriac, alongside strong Greek and Parthian influences, though some Arab cults were also attested at Edessa.

Penal transportation was the relocation of convicted criminals, or other persons regarded as undesirable, to a distant place, often a colony, for a specified term; later, specifically established penal colonies became their destination. While the prisoners may have been released once the sentences were served, they generally did not have the resources to return home.

A chain gang or road gang is a group of prisoners chained together to perform menial or physically challenging work as a form of punishment. Such punishment might include repairing buildings, building roads, or clearing land. The system was notably used in the convict era of Australia and in the Southern United States. By 1955 it had largely been phased out in the U.S., with Georgia among the last states to abandon the practice. North Carolina continued to use chain gangs into the 1970s. Chain gangs were reintroduced by a few states during the "get tough on crime" 1990s: In 1995, Alabama was the first state to revive them. The experiment ended after about one year in all states except Arizona, where in Maricopa County inmates can still volunteer for a chain gang to earn credit toward a high school diploma or avoid disciplinary lockdowns for rule infractions.

A labor camp or work camp is a detention facility where inmates are forced to engage in penal labor as a form of punishment. Labor camps have many common aspects with slavery and with prisons. Conditions at labor camps vary widely depending on the operators. Convention no. 105 of the United Nations International Labour Organization (ILO), adopted internationally on 27 June 1957, abolished camps of forced labor.

The Rostra was a large platform built in the city of Rome that stood during the republican and imperial periods. Speakers would stand on the rostra and face the north side of the Comitium towards the senate house and deliver orations to those assembled in between. It is often referred to as a suggestus or tribunal, the first form of which dates back to the Roman Kingdom, the Vulcanal.

The Mamertine Prison, in antiquity the Tullianum, was a prison (carcer) with a dungeon (oubliette) located in the Comitium in ancient Rome. It is said to have been built in the 7th century BC and was situated on the northeastern slope of the Capitoline Hill, facing the Curia and the imperial fora of Nerva, Vespasian, and Augustus. Located between it and the Tabularium was a flight of stairs leading to the Arx of the Capitoline known as the Gemonian stairs.

Prison reform is the attempt to improve conditions inside prisons, improve the effectiveness of a penal system, or implement alternatives to incarceration. It also focuses on ensuring the reinstatement of those whose lives are impacted by crimes.

In ancient Rome, the quindecimviri sacris faciundis were the fifteen members of a college (collegium) with priestly duties. They guarded the Sibylline Books, scriptures which they consulted and interpreted at the request of the Senate. This collegium also oversaw the worship of any foreign gods which were introduced to Rome. They were also responsible for responding to divine advice and omens.

Penal labour is a term for various kinds of forced labour that prisoners are required to perform, typically manual labour. The work may be light or hard, depending on the context. Forms of sentence involving penal labour have included involuntary servitude, penal servitude, and imprisonment with hard labour. The term may refer to several related scenarios: labour as a form of punishment, the prison system used as a means to secure labour, and labour as providing occupation for convicts. These scenarios can be applied to those imprisoned for political, religious, war, or other reasons as well as to criminal convicts.

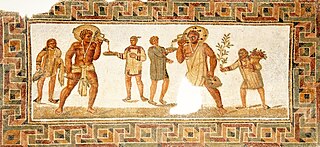

Slavery in ancient Rome played an important role in society and the economy. Unskilled or low-skill slaves labored in the fields, mines, and mills with few opportunities for advancement and little chance of freedom. Skilled and educated slaves—including artisans, chefs, domestic staff and personal attendants, entertainers, business managers, accountants and bankers, educators at all levels, secretaries and librarians, civil servants, and physicians—occupied a more privileged tier of servitude and could hope to obtain freedom through one of several well-defined paths with protections under the law. The possibility of manumission and subsequent citizenship was a distinguishing feature of Rome's system of slavery, resulting in a significant and influential number of freedpersons in Roman society.

In the military of ancient Rome, fustuarium or fustuarium supplicium was a severe form of military discipline in which a soldier was cudgeled to death.

The Piracy Act 1717, sometimes called the Transportation Act 1717, was an Act of the Parliament of Great Britain that established a regulated, bonded system to transport criminals to colonies in North America for indentured service, as a punishment for those convicted or attainted in Great Britain, excluding Scotland. The Act established a seven-year transportation sentence as a punishment for people convicted of lesser felonies, and a fourteen-year sentence for more serious crimes, in lieu of capital punishment. Completion of the sentence had the effect of a pardon; the punishment for returning before completion was death. It is commonly accepted that 30,000 convicts may have been transported to the British American colonies, with some estimates going as high as 50,000.

Ecclesiastical prisons were penal institutions maintained by the Catholic Church. At various times, they were used for the incarceration both of clergy accused of various crimes, and of laity accused of specifically ecclesiastical crimes; prisoners were sometimes held in custody while awaiting trial, sometimes as part of an imposed sentence. The use of ecclesiastical prisons began as early as the third or fourth century AD, and remained common through the early modern era.

Vagrancy is the condition of wandering homelessness without regular employment or income. Vagrants usually live in poverty and support themselves by travelling while engaging in begging, scavenging, petty theft, temporary work, or social security. Historically, vagrancy in Western societies was associated with petty crime, begging and lawlessness, and punishable by law with forced labor, military service, imprisonment, or confinement to dedicated labor houses.

A prison, also known as a jail, gaol, penitentiary, detention center, correction center, correctional facility, or remand center, is a facility where people are confined against their will and denied a variety of freedoms under the authority of the state, generally as punishment for various crimes. Authorities most commonly use prisons within a criminal-justice system: people charged with crimes may be imprisoned until their trial; those who have pled or been found guilty of crimes at trial may be sentenced to a specified period of imprisonment.

Damnatio ad bestias was a form of Roman capital punishment where the condemned person was killed by wild animals, usually lions or other big cats. This form of execution, which first appeared during the Roman Republic around the 2nd century BC, had been part of a wider class of blood sports called Bestiarii.

Childbirth in ancient Rome was dangerous for both the mother and the child. Mothers usually would rely on religious superstition to avoid death. Certain customs such as lying in bed after childbirth and using plants and herbs as relief were also practiced. Midwives assisted the mothers in birth. Once children were born they would not be given a name until 8 or 9 days after their birth. The number depended on if they were male or female. Once the days had past, the child would be gifted a name and a bulla during a ceremony. When a child reached the age of 1, they would gain legal privileges which could lead to citizenship. Children 7 and under were considered infants, and were under the care of women. From a age 8 until they reached adulthood children were expected to help with housework. The age of adulthood was 12 for girls, or 14 for boys. Children would often have a variety of toys to play with. If a child died they could be buried or cremated. Some would be commemorated in Roman religious tradition.

The tresviri capitales or tresviri nocturni were one of the Vigintisexviri colleges in Ancient Rome. They were a group of three men that managed police and firefighting. Despite this they were feared by the Roman people due to their police roles, and they were condemned due to their neglect of firefighting during an unknown incident, which was likely the Great Fire of Rome. The Roman people gave the Tresviri Capitales the nickname nocturni due to the night patrols they managed. They were elected by the Urban praetors and later Tribal Assembly.

In the Roman Republic, triumviri or tresviri were special commissions of three men appointed for specific administrative tasks apart from the regular duties of Roman magistrates.

References

- ↑ Richard A. Bauman, Crime and Punishment in Ancient Rome (Routledge, 1996), p. 23.

- ↑ Fergus Millar, "Condemnation to Hard Labour in the Roman Empire, from the Julio-Claudians to Constantine," in Rome, the Greek World, and the East: Society and Culture in the Roman Empire (University of North Carolina Press, 2004), vol. 2, pp. 122 ("the carcer was employed for the retention of prisoners awaiting trial or punishment," but "any tendency for it to be used as a place of sentence was always resisted"), and p. 130.

- ↑ Millar, "Condemnation to Hard Labour in the Roman Empire," p. 131.

- ↑ Edward M. Peters, "Prison before the Prison: The Ancient and Medieval Worlds," in The Oxford History of the Prison: The Practice of Punishment in West Society (Oxford University Press, 1995), p. 14.

- ↑ Millar, "Condemnation to Hard Labour," pp. 123, 131 et passim.

- ↑ Millar, "Condemnation to Hard Labour," p. 122ff.

- 1 2 Ripley, George; Dana, Charles Anderson (1883). The American Cyclopaedia: A Popular Dictionary for General Knowledge. D. Appleton and Company.

- 1 2 Wansink, Craig S. (1996-01-01). Chained in Christ: The Experience and Rhetoric of Paul's Imprisonments. A&C Black. ISBN 978-1-85075-605-7.

- ↑ Roth, Mitchel P. (2006). Prisons and Prison Systems: A Global Encyclopedia. Greenwood Publishing Group. ISBN 978-0-313-32856-5.

- ↑ Andrew Lintott, Violence in Republican Rome (Oxford University Press, 1999, 2nd ed.), p. 102.

- ↑ Gaughan, Judy E. (2010-01-01). Murder Was Not a Crime: Homicide and Power in the Roman Republic. University of Texas Press. ISBN 978-0-292-77992-1.

- ↑ Rome; Johnson, Allan Chester; Coleman-Norton, Paul Robinson; Bourne, Frank Card (1961). Ancient Roman Statutes: A Translation, with Introduction, Commentary, Glossary, and Index. University of Texas Press. ISBN 9780292731639.

- ↑ Morris, Norval; Rothman, David J. (1998). The Oxford History of the Prison: The Practice of Punishment in Western Society. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-511814-8.

- ↑ Kyle, Donald G. (2001). Spectacles of Death in Ancient Rome. Psychology Press. ISBN 978-0-415-24842-6.

- ↑ Livy, Periocha 11.

- ↑ John E. Stambaugh, The Ancient Roman City (Johns Hopkins University Press, 1988), p. 347, note 4, and p. 348, note 13; O.F. Robinson, Ancient Rome: City Planning and Administration (Routledge, 1994), p. 105.

- 1 2 Robinson, O. F. (2007-03-12). Penal Practice and Penal Policy in Ancient Rome. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-134-11722-2.

- ↑ Drake, H. A. (2016-12-05). Violence in Late Antiquity: Perceptions and Practices. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-351-87574-5.

- ↑ Ermatinger, James William (2007). Daily Life of Christians in Ancient Rome. Greenwood Publishing Group. ISBN 978-0-313-33564-8.