Auschwitz concentration camp was a complex of over 40 concentration and extermination camps operated by Nazi Germany in occupied Poland during World War II and the Holocaust. It consisted of Auschwitz I, the main camp (Stammlager) in Oświęcim; Auschwitz II-Birkenau, a concentration and extermination camp with gas chambers; Auschwitz III-Monowitz, a labor camp for the chemical conglomerate IG Farben; and dozens of subcamps. The camps became a major site of the Nazis' final solution to the Jewish question.

Nazi Germany used six extermination camps, also called death camps, or killing centers, in Central Europe during World War II to systematically murder over 2.7 million people – mostly Jews – in the Holocaust. The victims of death camps were primarily murdered by gassing, either in permanent installations constructed for this specific purpose, or by means of gas vans. The six extermination camps were Chełmno, Belzec, Sobibor, Treblinka, Majdanek and Auschwitz-Birkenau. Auschwitz and Majdanek death camps also used extermination through labour in order to kill their prisoners.

The Nuremberg trials were held by the Allies against representatives of the defeated Nazi Germany, for plotting and carrying out invasions of other countries, and other crimes, in World War II.

Zyklon B was the trade name of a cyanide-based pesticide invented in Germany in the early 1920s. It consisted of hydrogen cyanide, as well as a cautionary eye irritant and one of several adsorbents such as diatomaceous earth. The product is notorious for its use by Nazi Germany during the Holocaust to murder approximately 1.1 million people in gas chambers installed at Auschwitz-Birkenau, Majdanek, and other extermination camps.

I. G. Farbenindustrie AG, commonly known as IG Farben, was a German chemical and pharmaceutical conglomerate. Formed in 1925 from a merger of six chemical companies—BASF, Bayer, Hoechst, Agfa, Chemische Fabrik Griesheim-Elektron, and Chemische Fabrik vorm. Weiler Ter Meer—it was seized by the Allies after World War II and divided back into its constituent companies.

The German camps in occupied Poland during World War II were built by the Nazis between 1939 and 1945 throughout the territory of the Polish Republic, both in the areas annexed in 1939, and in the General Government formed by Nazi Germany in the central part of the country (see map). After the 1941 German attack on the Soviet Union, a much greater system of camps was established, including the world's only industrial extermination camps constructed specifically to carry out the "Final Solution to the Jewish Question".

Gross-Rosen was a network of Nazi concentration camps built and operated by Nazi Germany during World War II. The main camp was located in the German village of Gross-Rosen, now the modern-day Rogoźnica in Lower Silesian Voivodeship, Poland; directly on the rail-line between the towns of Jawor (Jauer) and Strzegom (Striegau). Its prisoners were mostly Jews, Poles and Soviet citizens.

The United States of America vs. Friedrich Flick, et al. or Flick trial was the fifth of twelve Nazi war crimes trials held by United States authorities in their occupation zone in Germany (Nuremberg) after World War II. It was the first of three trials of leading industrialists of Nazi Germany; the two others were the IG Farben Trial and the Krupp Trial.

The United States of America vs. Carl Krauch, et al., also known as the IG Farben Trial, was the sixth of the twelve trials for war crimes the U.S. authorities held in their occupation zone in Germany (Nuremberg) after the end of World War II. IG Farben was the private German chemicals company allied with the Nazis that manufactured the Zyklon B gas used to commit genocide against millions of European Jews in the Holocaust.

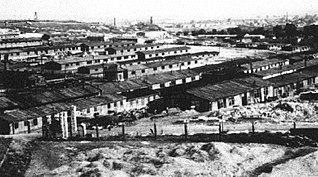

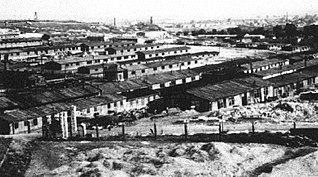

Monowitz was a Nazi concentration camp and labor camp (Arbeitslager) run by Nazi Germany in occupied Poland from 1942–1945, during World War II and the Holocaust. For most of its existence, Monowitz was a subcamp of the Auschwitz concentration camp; from November 1943 it and other Nazi subcamps in the area were jointly known as "Auschwitz III-subcamps". In November 1944 the Germans renamed it Monowitz concentration camp, after the village of Monowice where it was built, in the annexed portion of Poland. SS Hauptsturmführer (Captain) Heinrich Schwarz was commandant from November 1943 to January 1945.

Extermination through labour is a term that was adopted to describe forced labor in Nazi concentration camps in light of the high mortality rate and poor conditions; in some camps a majority of prisoners died within a few months. In the 21st century, research has questioned whether there was a general policy of extermination through labor in the Nazi concentration camp system because of widely varying conditions between camps. German historian Jens-Christian Wagner argues that the camp system involved the exploitation of forced labor of some prisoners and the systematic murder of others, especially Jews, with only limited overlap between these two groups.

Arbeitslager is a German language word which means labor camp. Under Nazism, the German government used forced labor extensively, starting in the 1930s but most especially during World War II. Another term was Zwangsarbeitslager.

Vaivara was the largest of the 22 concentration and labor camps established in occupied Estonia by the Nazi regime during World War II. It had 20,000 Jewish prisoners pass through its gates, mostly from the Vilna and Kovno Ghettos, but also from Latvia, Poland, Hungary and the Theresienstadt concentration camp. Vaivara was one of the last camps to be established. It existed from August 1943 to February 1944.

Charles Joseph Coward, known as the "Count of Auschwitz", was a British soldier captured during the Second World War who rescued Jews from Auschwitz and claimed he had smuggled himself into the camp for one night, subsequently testifying about his experience at the IG Farben Trial at Nuremberg. He also smuggled at least several hundred Jewish prisoners out of concentration camps.

The Fürstengrube subcamp was organized in the summer of 1943 at the Fürstengrube hard coal mine in the town of Wesoła (Wessolla) near Myslowice (Myslowitz), approximately 30 kilometers (19 mi) from Auschwitz concentration camp. The mine, which IG Farbenindustrie AG acquired in February 1941, was to supply hard coal for the IG Farben factory being built in Auschwitz. Besides the old Fürstengrube mine, called the Altanlage, a new mine (Fürstengrube-Neuanlage) had been designed and construction had begun; it was to provide for greater coal output in the future. Coal production at the new mine was anticipated to start in late 1943, so construction was treated as very urgent; however, that plan proved to be unfeasible.

Otto Ambros was a German chemist and Nazi war criminal. He is known for his wartime work on synthetic rubber and nerve agents. After the war he was tried at Nuremberg and convicted of crimes against humanity for his use of slave labor from the Auschwitz III–Monowitz concentration camp.

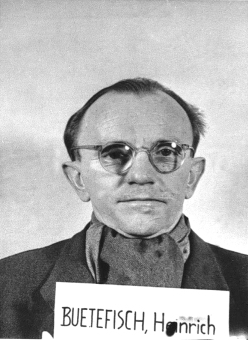

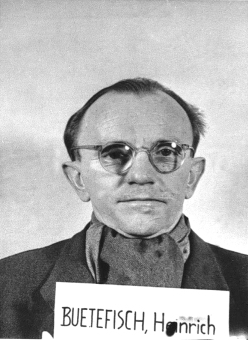

Heinrich Bütefisch was a German chemist, manager at IG Farben, and Nazi war criminal. He was an Obersturmbannführer in the SS.

Forced labor was an important and ubiquitous aspect of the Nazi concentration camps which operated in Nazi Germany and German-occupied Europe between 1933 and 1945. It was the harshest and most inhumane part of a larger system of forced labor in Nazi Germany.