Gaius Julius Caesar Augustus, also known as Octavian, was the founder of the Roman Empire. He reigned as the first Roman emperor from 27 BC until his death in AD 14. The reign of Augustus initiated an imperial cult, as well as an era of imperial peace in which the Roman world was largely free of armed conflict. The Principate system of government was established during his reign and lasted until the Crisis of the Third Century.

Marcus Antonius, commonly known in English as Mark Antony, was a Roman politician and general who played a critical role in the transformation of the Roman Republic from a constitutional republic into the autocratic Roman Empire.

Year 43 BC was either a common year starting on Sunday, Monday or Tuesday or a leap year starting on Sunday or Monday of the Julian calendar and a common year starting on Monday of the Proleptic Julian calendar. At the time, it was known as the Year of the Consulship of Pansa and Hirtius. The denomination 43 BC for this year has been used since the early medieval period, when the Anno Domini calendar era became the prevalent method in Europe for naming years.

This article concerns the period 49 BC – 40 BC.

Marcus Junius Brutus was a Roman politician, orator, and the most famous of the assassins of Julius Caesar. After being adopted by a relative, he used the name Quintus Servilius Caepio Brutus, which was retained as his legal name. He is often referred to simply as Brutus.

The Second Triumvirate was an extraordinary commission and magistracy created for Mark Antony, Lepidus, and Octavian to give them practically absolute power. It was formally constituted by law on 27 November 43 BC with a term of five years; it was renewed in 37 BC for another five years before expiring in 32 BC. Constituted by the lex Titia, the triumvirs were given broad powers to make or repeal legislation, issue judicial punishments without due process or right of appeal, and appoint all other magistrates. The triumvirs also split the Roman world into three sets of provinces.

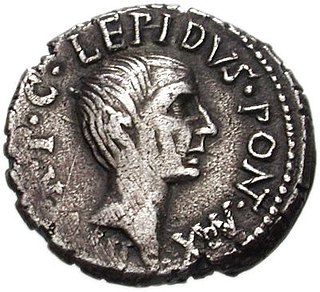

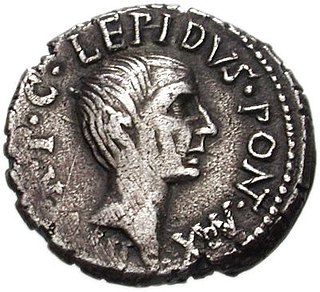

Marcus Aemilius Lepidus was a Roman general and statesman who formed the Second Triumvirate alongside Octavian and Mark Antony during the final years of the Roman Republic. Lepidus had previously been a close ally of Julius Caesar. He was also the last pontifex maximus before the Roman Empire, and (presumably) the last interrex and magister equitum to hold military command.

Fulvia was an aristocratic Roman woman who lived during the Late Roman Republic. Fulvia's birth into an important political dynasty facilitated her relationships and, later on, marriages to Publius Clodius Pulcher, Gaius Scribonius Curio, and Mark Antony. All of these men would go on to lead increasingly promising political careers as populares, tribunes, and supporters of Julius Caesar.

Julia was the mother of the triumvir general Mark Antony.

Gaius Antonius Hybrida was a politician of the Roman Republic. He was the second son of Marcus Antonius and brother of Marcus Antonius Creticus; his mother is unknown. He was also the uncle of the famed triumvir Mark Antony. He had two children, Antonia Hybrida Major and Antonia Hybrida Minor.

Lucius Munatius Plancus was a Roman senator, consul in 42 BC, and censor in 22 BC with Paullus Aemilius Lepidus. He is one of the classic historical examples of men who have managed to survive very dangerous circumstances by constantly shifting their allegiances. Beginning his career under Julius Caesar, he allied with his assassin Decimus Junius Brutus in 44 BC, then with the Second Triumvirate in 43 BC, joining Mark Antony in 40 BC, and deserting him for Octavian in 32 BC. He also founded the cities of Augusta Raurica and Lugdunum. His tomb is still visible at Gaeta.

Lucius Aemilius Paullus was a Roman politician. He was the brother of triumvir Marcus Aemilius Lepidus and son to Marcus Aemilius Lepidus the consul of 78 BC. His mother may have been a daughter of Lucius Appuleius Saturninus.

Quintus Pedius was a Roman politician and general who lived during the late Republic. He served as a military officer under Julius Caesar for most of his career. Serving with Caesar during the civil war, he was elected praetor in 48 BC and was given a triumph for victories over the Pompeians during the civil war's second Spanish campaign.

The Bellum Siculum was an Ancient Roman civil war waged between 42 BC and 36 BC by the forces of the Second Triumvirate and Sextus Pompey, the last surviving son of Pompey the Great and the last leader of the Optimate faction. The war consisted of mostly a number of naval engagements throughout the Mediterranean Sea and a land campaign primarily in Sicily that eventually ended in a victory for the Triumvirate and Sextus Pompey's death. The conflict is notable as the last stand of any organised opposition to the Triumvirate.

Junia, called Junia Secunda by modern historians to distinguish her from her sisters, was an ancient Roman woman who lived in the 1st century BC. She was the sister of Marcus Brutus, and was married to the triumvir Marcus Aemilius Lepidus.

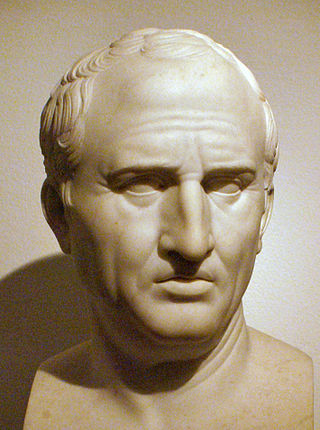

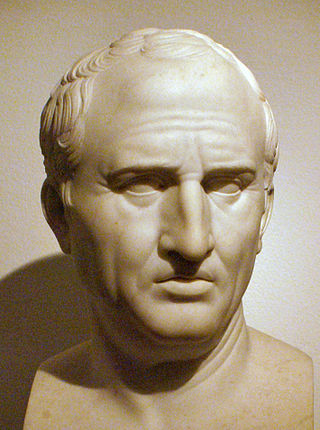

The Philippics are a series of 14 speeches composed by Cicero in 44 and 43 BC, condemning Mark Antony. Cicero likened these speeches to those of Demosthenes against Philip II of Macedon; both Demosthenes' and Cicero's speeches became known as Philippics. Cicero's Second Philippic is styled after Demosthenes' On the Crown.

The political career of Marcus Tullius Cicero began in 76 BC with his election to the office of quaestor, and ended in 43 BC, when he was assassinated upon the orders of Mark Antony. Cicero, a Roman statesman, lawyer, political theorist, philosopher, and Roman constitutionalist, reached the height of Roman power, the Consulship, and played a critical role in the transformation of the Roman Republic into the Roman Empire. A contemporary of Julius Caesar, Cicero is widely considered one of Rome's greatest orators and prose stylists.

The constitutional reforms of Augustus were a series of laws that were enacted by the Roman Emperor Augustus between 30 BC and 2 BC, which transformed the Constitution of the Roman Republic into the Constitution of the Roman Empire. The era during which these changes were made began when Augustus defeated Mark Antony and Cleopatra at the Battle of Actium in 31 BC, and ended when the Roman Senate granted Augustus the title "Pater Patriae" in 2 BC.

The proscription of Sulla was a reprisal campaign by the Roman proconsul and later dictator, Lucius Cornelius Sulla, to eliminate his enemies in the aftermath of his victory in the civil war of 83–82 BC.

The War of Mutina was a civil war between the Roman Senate and Mark Antony in Northern Italy. It was the first civil war after the assassination of Julius Caesar. The main issue of the war were attempts by the Senate to resist Antony's forceful assumption of the strategically important provinces of Transalpine and Cisalpine Gaul from their governors. The Senate, led by Cicero and the consuls, attempted to woo Julius Caesar's heir to fight against Antony. Octavian, however, would pursue his own agenda.