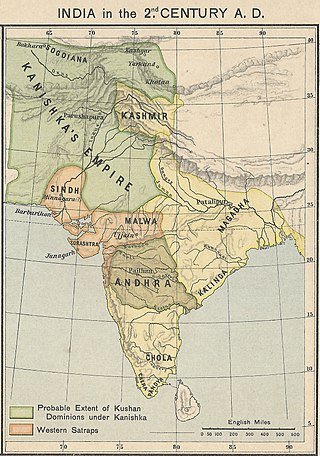

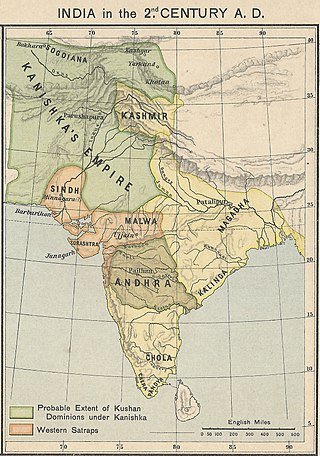

Kanishka I, Kanishka or Kanishka the Great, was an emperor of the Kushan dynasty, under whose reign the empire reached its zenith. He is famous for his military, political, and spiritual achievements. A descendant of Kujula Kadphises, founder of the Kushan empire, Kanishka came to rule an empire extending from Central Asia and Gandhara to Pataliputra on the Gangetic plain. The main capital of his empire was located at Puruṣapura (Peshawar) in Gandhara, with another major capital at Mathura. Coins of Kanishka were found in Tripuri.

The Kushan Empire was a syncretic empire formed by the Yuezhi in the Bactrian territories in the early 1st century. It spread to encompass much of what is now Uzbekistan, Afghanistan, Pakistan, and Northern India, at least as far as Saketa and Sarnath, near Varanasi, where inscriptions have been found dating to the era of the Kushan emperor Kanishka the Great.

Hermaeus Soter or Hermaios Soter was a Western Indo-Greek king of the Eucratid Dynasty, who ruled the territory of Paropamisade in the Hindu-Kush region, with his capital in Alexandria of the Caucasus. Bopearachchi dates Hermaeus to c. 90–70 BCE and R. C. Senior to c. 95–80 BCE.

Kujula Kadphises was a Kushan prince who united the Yuezhi confederation in Bactria during the 1st century CE, and became the first Kushan emperor. According to the Rabatak inscription, he was the great grandfather of the great Kushan king Kanishka I. He is considered the founder of the Kushan Empire.

Vima Kadphises was a Kushan emperor from approximately 113 to 127 CE. According to the Rabatak inscription, he was the son of Vima Takto and the father of Kanishka.

Vima Takto or Vima Taktu was a Kushan emperor who reigned c. 80–90 CE.

Vāsudeva I was a Kushan emperor, last of the "Great Kushans." Named inscriptions dating from year 64 to 98 of Kanishka's era suggest his reign extended from at least 191 to 232 CE. He ruled in Northern India and Central Asia, where he minted coins in the city of Balkh (Bactria). He probably had to deal with the rise of the Sasanians and the first incursions of the Kushano-Sasanians in the northwest of his territory.

Oesho is a deity found on coins of 2nd to 6th-century, particularly the 2nd-century Kushan era. He was apparently one of the titular deities of the Kushan dynasty. Oesho is an early Kushan deity that is regarded as an amalgamation of Shiva.

Bactrian is an extinct Eastern Iranian language formerly spoken in the Central Asian region of Bactria and used as the official language of the Kushan and the Hephthalite empires.

Mujatria, previously read Hajatria, is the name of an Indo-Scythian ruler, the son of Kharahostes as mentioned on his coins.

Surkh Kotal (Persian: چشمه شیر Chashma-i Shir; also called Sar-i Chashma, is an ancient archaeological site located in the southern part of the region of Bactria, about 18 kilometres north of the city of Puli Khumri, the capital of Baghlan Province of Afghanistan. It is the location of monumental constructions made during the rule of the Kushans. Huge temples, statues of Kushan rulers and the Surkh Kotal inscription, which revealed part of the chronology of early Kushan emperors were all found there. The Rabatak inscription which gives remarkable clues on the genealogy of the Kushan dynasty was also found in the Robatak village just outside the site.

Within Buddhist mythology, Sadashkana according to the gold plate inscription of Senavarman, mentions Sadashkana as the Devaputra, son of maharaja rayatiraya Kujula Kataphsa :

Vāsishka was a Kushan emperor, who seems to have had a short reign following Kanishka II.

Nicholas Sims-Williams, FBA is a British professor of the School of Oriental and African Studies (SOAS), University of London, where he is the Research Professor of Iranian and Central Asian Studies at the Department of the Languages and Cultures of Near and Middle East. Sims-Williams is a scholar who specializes in Central Asian history, particularly the study of Sogdian and Bactrian languages. He is also a member of the advisory council of the Iranian Studies journal.

The legacy of the Indo-Greeks starts with the formal end of the Indo-Greek Kingdom from the 1st century, as the Greek communities of central Asia and northwestern India lived under the control of the Kushan branch of the Yuezhi, Indo-Scythians and Indo-Parthian Kingdom. The Kushans founded the Kushan Empire, which was to prosper for several centuries. In the south, the Greeks were under the rule of the Scythian Western Kshatrapas.

In the coinage of the North Indian and Central Asian Kushan Empire the main coins issued were gold, weighing 7.9 grams, and base metal issues of various weights between 12 g and 1.5 g. Little silver coinage was issued, but in later periods the gold used was debased with silver.

Dilberjin Tepe, also Dilberjin or Delbarjin, is the modern name for the remains of an ancient town in modern (northern) Afghanistan. The town was perhaps founded in the time of the Achaemenid Empire. Under the Kushan Empire it became a major local centre. After the Kushano-Sassanids the town was abandoned.

The Wardak Vase is an ancient globular-shaped buddhist copper vase that was found as part of a stupa relic deposit in the early nineteenth century in the Wardak Province of Afghanistan. The importance of the vase lies in the long Kharoshthi inscription which dates the objects to around 178 AD and claims that the stupa contained the sacred relics of the Buddha. Since 1880, the vase has been part of the British Museum's Asian collection.

Kushan art, the art of the Kushan Empire in northern India, flourished between the 1st and the 4th century CE. It blended the traditions of the Greco-Buddhist art of Gandhara, influenced by Hellenistic artistic canons, and the more Indian art of Mathura. Kushan art follows the Hellenistic art of the Greco-Bactrian Kingdom as well as Indo-Greek art which had been flourishing between the 3rd century BCE and 1st century CE in Bactria and northwestern India, and the succeeding Indo-Scythian art. Before invading northern and central India and establishing themselves as a full-fledged empire, the Kushans had migrated from northwestern China and occupied for more than a century these Central Asian lands, where they are thought to have assimilated remnants of Greek populations, Greek culture, and Greek art, as well as the languages and scripts which they used in their coins and inscriptions: Greek and Bactrian, which they used together with the Indian Brahmi script.

Rupiamma was a Great Satrap in India during the 2nd century CE, who is known from an inscription found at Pauni in Central India, south of the Narmada river.