The Lakota are a Native American people. Also known as the Teton Sioux, they are one of the three prominent subcultures of the Sioux people, with the Eastern Dakota (Santee) and Western Dakota (Wičhíyena). Their current lands are in North and South Dakota. They speak Lakȟótiyapi—the Lakota language, the westernmost of three closely related languages that belong to the Siouan language family.

The Sioux or Oceti Sakowin are groups of Native American tribes and First Nations peoples from the Great Plains of North America. The Sioux have two major linguistic divisions: the Dakota and Lakota peoples. Collectively, they are the Očhéthi Šakówiŋ, or "Seven Council Fires". The term "Sioux", an exonym from a French transcription ("Nadouessioux") of the Ojibwe term "Nadowessi", can refer to any ethnic group within the Great Sioux Nation or to any of the nation's many language dialects.

The Pine Ridge Indian Reservation, also called Pine Ridge Agency, is an Oglala Lakota Indian reservation located within the U.S. state of South Dakota, with a small portion in Nebraska. Originally included within the territory of the Great Sioux Reservation, Pine Ridge was created by the Act of March 2, 1889, 25 Stat. 888. in the southwest corner of South Dakota on the Nebraska border. Today it consists of 3,468.85 sq mi (8,984 km2) of land area and is one of the largest reservations in the United States.

Lakota, also referred to as Lakhota, Teton or Teton Sioux, is a Siouan language spoken by the Lakota people of the Sioux tribes. Lakota is mutually intelligible with the two dialects of the Dakota language, especially Western Dakota, and is one of the three major varieties of the Sioux language.

The Brulé are one of the seven branches or bands of the Teton (Titonwan) Lakota American Indian people. They are known as Sičhą́ǧu Oyáte —Sicangu Oyate—, Sicangu Lakota, or "Burnt Thighs Nation". Learning the meaning of their name, the French called them the Brûlé. The name may have derived from an incident where they were fleeing through a grass fire on the plains.

The Rosebud Indian Reservation is an Indian reservation in South Dakota, United States. It is the home of the federally recognized Rosebud Sioux Tribe, who are Sicangu, a band of Lakota people. The Lakota name Sicangu Oyate translates as the "Burnt Thigh Nation", also known by the French term, the Brulé Sioux.

Benjamin Reifel, also known as Lone Feather, was a Lakota Sioux public administrator and politician. He had a career with the Bureau of Indian Affairs, retiring as area administrator. He ran for the US Congress from the East River region of South Dakota, and was elected as the first Lakota to serve in the House of Representatives. He served five terms as a Republican United States Congressman from the First District.

The Sisseton Wahpeton Oyate of the Lake Traverse Reservation, formerly Sisseton-Wahpeton Sioux Tribe/Dakota Nation, is a federally recognized tribe comprising two bands and two subdivisions of the Isanti or Santee Dakota people. They are on the Lake Traverse Reservation in northeast South Dakota.

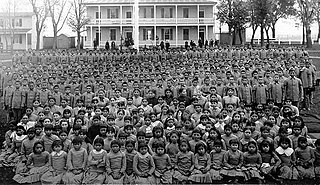

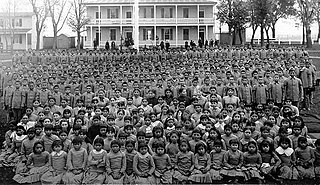

American Indian boarding schools, also known more recently as American Indian residential schools, were established in the United States from the mid-17th to the early 20th centuries with a primary objective of "civilizing" or assimilating Native American children and youth into Anglo-American culture. In the process, these schools denigrated Native American culture and made children give up their languages and religion. At the same time the schools provided a basic Western education. These boarding schools were first established by Christian missionaries of various denominations. The missionaries were often approved by the federal government to start both missions and schools on reservations, especially in the lightly populated areas of the West. In the late 19th and early 20th centuries especially, the government paid religious orders to provide basic education to Native American children on reservations, and later established its own schools on reservations. The Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA) also founded additional off-reservation boarding schools based on the assimilation model. These sometimes drew children from a variety of tribes. In addition, religious orders established off-reservation schools.

The Rapid City Indian Health Service Hospital formerly known as The Sioux San Hospital is an Indian Health Service hospital located in Rapid City, South Dakota. It was built in 1898 as a boarding school for Native Americans and turned into a sanitarium in 1933.

The Bureau of Indian Education (BIE), headquartered in the Main Interior Building in Washington, D.C., and formerly known as the Office of Indian Education Programs (OIEP), is a division of the U.S. Department of the Interior under the Assistant Secretary for Indian Affairs. It is responsible for the line direction and management of all BIE education functions, including the formation of policies and procedures, the supervision of all program activities, and the approval of the expenditure of funds appropriated for BIE education functions.

Rosebud Yellow Robe (Lacotawin) was a Native American folklorist, educator and writer of half Lakota Sioux birth. Rosebud was influenced by her father Chauncey Yellow Robe, and used storytelling, performance and books to introduce generations of children to Native American folklore and culture.

St. Joseph's Indian School is an American Indian boarding school, run by the Congregation of the Priests of the Sacred Heart just outside the city of Chamberlain, South Dakota, on the east side of the Missouri River. The school, located in the Roman Catholic Diocese of Sioux Falls and named after Saint Joseph, is operated by a religious institute of pontifical right that is independent of the diocese. The school is within two hours of three reservations of the Lakota people: the Cheyenne River Indian Reservation, the Lower Brule Indian Reservation and the Crow Creek Indian Reservation, whose children comprise the majority of students at the school. The Akta Lakota Museum and Cultural Center is located on the campus and is owned by the school.

Albert White Hat was a teacher of the Lakota language, and an activist for Sičháŋǧu Lakȟóta traditional culture. He translated the Lakota language for Hollywood movies, including the 1990 movie Dances with Wolves, and created a modern Lakota orthography and textbook.

Belva Cottier was an American Rosebud Sioux activist and social worker. She proposed the idea of occupying Alcatraz Island in 1964 and was one of the activists who led the protest for return of the island to Native Americans. She planned the first Occupation of Alcatraz, and the suit to claim the property for the Sioux. Concerned for the health of urban Indians, she conducted a study for the Department of Health, Education and Welfare, which resulted in her becoming the executive director of the first American Indian Health Center in the Bay area in 1972.

Chamberlain Indian School was an American Indian boarding school in Chamberlain, South Dakota, located on the east bank of the Missouri River. It was among 25 off-reservation boarding schools opened by the federal government by 1898 in the plains region. It was administered by the Bureau of Indian Affairs and operated until 1908

Flandreau Indian School (FIS), previously Flandreau Indian Vocational High School, is a boarding school for Native American children in unincorporated Moody County, South Dakota, adjacent to Flandreau. It is operated by the Bureau of Indian Education (BIE) and is off-reservation.

Pierre Indian Learning Center (PILC), also known as Pierre Indian School Learning Center, is a grade 1-8 tribal boarding school in Pierre, South Dakota. It is affiliated with the Bureau of Indian Education (BIE).

Chief Chauncey Yellow Robe was a Sičhą́ǧú educator, lecturer, actor, and Native American activist. His given name, Canowicakte, means "kill in woods," and he was nicknamed "Timber" in his youth.

St. Elizabeth's Boarding School for Indian Children was established in 1886 and remained in operation until 1967. It was located in the Wakpala area of the Standing Rock Reservation in South Dakota. This school was one of many schools established across the United States as part of an incentive to integrate Native Americans into the American Culture. St. Elizabeth's boarding school was one of the religious boarding schools from the Episcopal Church. The environment for education was harsh and difficult. Children were often forced to learn how to do manual labor and to abandon their culture. There were many prominent teachers and leaders at St. Elizabeths Indian School. Instructors like Mary Frances helped organize the children and keep the school running. There were also different school administrators over the years that had different strategies on how to instruct the children and also had different opinions on Native Americans. Daily life at this school was interesting and varied between the boys and the girls and what day of the week it was. One problem was that they lacked the resources to care for the children. The students would do manual labor to support the school. On Sundays they were expected to attend church services. Where they would sing hymns and read in there native language. This may have been the only opportunity for them to get a glimpse of there families, although they were not allowed to see them or talk to them. Sundays were also a more relaxed day where they could play and sleep longer. The education and focus of the curriculum was to help Native American Children assimilate as was the goal of the U.S. Government at the time. Students took classes like English, literature, and geography.