Indian religions, sometimes also termed Dharmic religions or Indic religions, are the religions that originated in the Indian subcontinent. These religions, which include Buddhism, Hinduism, Jainism, and Sikhism, are also classified as Eastern religions. Although Indian religions are connected through the history of India, they constitute a wide range of religious communities, and are not confined to the Indian subcontinent.

Nirvana is a concept in Indian religions, the extinguishing of the passions which is the ultimate state of soteriological release and the liberation from duḥkha ('suffering') and saṃsāra, the cycle of birth and rebirth.

Reincarnation, also known as rebirth or transmigration, is the philosophical or religious concept that the non-physical essence of a living being begins a new life in a different physical form or body after biological death. In most beliefs involving reincarnation, the soul of a human being is immortal and does not disperse after the physical body has perished. Upon death, the soul merely becomes transmigrated into a newborn baby or an animal to continue its immortality. The term transmigration means the passing of a soul from one body to another after death.

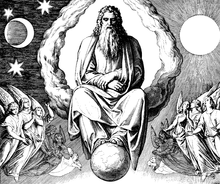

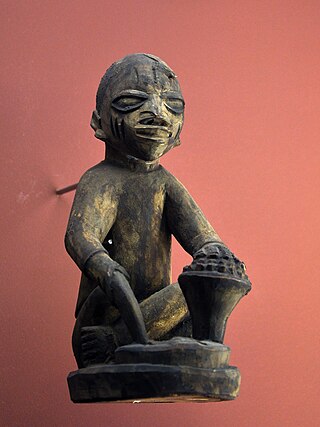

A creator deity or creator god is a deity responsible for the creation of the Earth, world, and universe in human religion and mythology. In monotheism, the single God is often also the creator. A number of monolatristic traditions separate a secondary creator from a primary transcendent being, identified as a primary creator.

Indra is the king of the devas and Svarga in Hinduism. He is associated with the sky, lightning, weather, thunder, storms, rains, river flows, and war.

Asuras are a class of beings in Indian religions. They are described as power-seeking demons related to the more benevolent Devas in Hinduism. In its Buddhist context, the word is translated as "titan", "demigod", or "antigod".

Saṃsāra is a Pali and Sanskrit word that means "wandering" as well as "world," wherein the term connotes "cyclic change" or, less formally, "running around in circles." Saṃsāra is referred to with terms or phrases such as transmigration/reincarnation, karmic cycle, or Punarjanman, and "cycle of aimless drifting, wandering or mundane existence". When related to the theory of karma it is the cycle of death and rebirth.

Moksha, also called vimoksha, vimukti, and mukti, is a term in Hinduism, Buddhism, Jainism and Sikhism for various forms of emancipation, liberation, nirvana, or release. In its soteriological and eschatological senses, it refers to freedom from saṃsāra, the cycle of death and rebirth. In its epistemological and psychological senses, moksha is freedom from ignorance: self-realization, self-actualization and self-knowledge.

Trailokya literally means "three worlds". It can also refer to "three spheres," "three planes of existence," and "three realms".

Generally speaking, Buddhism is a religion that does not include the belief in a monotheistic creator deity. As such, it has often been described as either (non-materialistic) atheism or as nontheism, though these descriptions have been challenged by other scholars, since some forms of Buddhism do posit different kinds of transcendent, unborn, and unconditioned ultimate realities.

Loka is a concept in Hinduism and other Indian religions, that may be translated as a planet, the universe, a plane, or a realm of existence. In some philosophies, it may also be interpreted as a mental state that one can experience. A primary concept in several Indian religions is the idea that different lokas are home to various divine beings, and one takes birth in such realms based on their karma.

Saṃsāra in Buddhism and Hinduism is the beginningless cycle of repeated birth, mundane existence and dying again. Samsara is considered to be dukkha, suffering, and in general unsatisfactory and painful, perpetuated by desire and avidya (ignorance), and the resulting karma.

Brahmā is a leading God (deva) and heavenly king in Buddhism. He is considered as a protector of teachings (dharmapala), and he is never depicted in early Buddhist texts as a creator god. In Buddhist tradition, it was the deity Brahma Sahampati who appeared before the Buddha and invited him to teach, once the Buddha attained enlightenment.

Jain cosmology is the description of the shape and functioning of the Universe (loka) and its constituents according to Jainism. Jain cosmology considers the universe as an uncreated entity that has existed since infinity with neither beginning nor end. Jain texts describe the shape of the universe as similar to a man standing with legs apart and arms resting on his waist. This Universe, according to Jainism, is broad at the top, narrow at the middle and once again becomes broad at the bottom.

Buddhism and Hinduism have common origins in the culture of Ancient India. Buddhism arose in the Gangetic plains of Eastern India in the 5th century BCE during the Second Urbanisation. Hinduism developed as a fusion or synthesis of practices and ideas from the ancient Vedic religion and elements and deities from other local Indian traditions. This Hindu synthesis emerged after the Vedic period, between 500–200 BCE and c. 300 CE, in or after the period of the second urbanisation, and during the early classical period of Hinduism, when the Epics and the first Puranas were composed.

According to Jain doctrine, the universe and its constituents—soul, matter, space, time, and principles of motion—have always existed. Jainism does not support belief in a creator deity. All the constituents and actions are governed by universal natural laws. It is not possible to create matter out of nothing and hence the sum total of matter in the universe remains the same. Jain texts claim that the universe consists of jiva and ajiva. The soul of each living being is unique and uncreated and has existed during beginningless time.[a]

Dualism in cosmology or dualistic cosmology is the moral or spiritual belief that two fundamental concepts exist, which often oppose each other. It is an umbrella term that covers a diversity of views from various religions, including both traditional religions and scriptural religions.

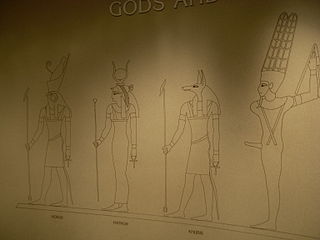

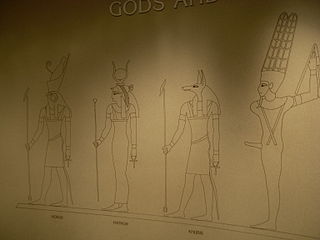

Polytheism is the belief in or worship of more than one god. According to Oxford Reference, it is not easy to count gods, and so not always obvious whether an apparently polytheistic religion, such as Chinese Folk Religions, is really so, or whether the apparent different objects of worship are to be thought of as manifestations of a singular divinity. Polytheistic belief is usually assembled into a pantheon of gods and goddesses, along with their own religious sects and rituals. Polytheism is a type of theism. Within theism, it contrasts with monotheism, the belief in a singular God who is, in most cases, transcendent.

Jīva or Ātman is a philosophical term used within Jainism to identify the soul. As per Jain cosmology, jīva or soul is the principle of sentience and is one of the tattvas or one of the fundamental substances forming part of the universe. The Jain metaphysics, states Jagmanderlal Jaini, divides the universe into two independent, everlasting, co-existing and uncreated categories called the jiva (soul) and the ajiva. This basic premise of Jainism makes it a dualistic philosophy. The jiva, according to Jainism, is an essential part of how the process of karma, rebirth and the process of liberation from rebirth works.

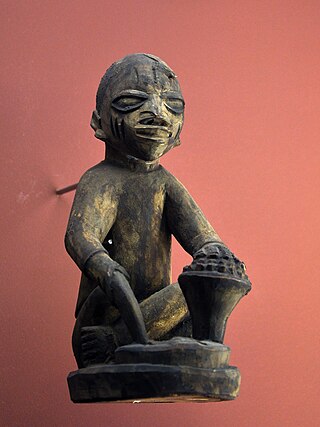

A deity or god is a supernatural being considered to be sacred and worthy of worship due to having authority over the universe, nature or human life. The Oxford Dictionary of English defines deity as a god or goddess, or anything revered as divine. C. Scott Littleton defines a deity as "a being with powers greater than those of ordinary humans, but who interacts with humans, positively or negatively, in ways that carry humans to new levels of consciousness, beyond the grounded preoccupations of ordinary life".