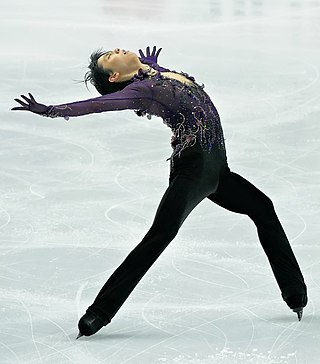

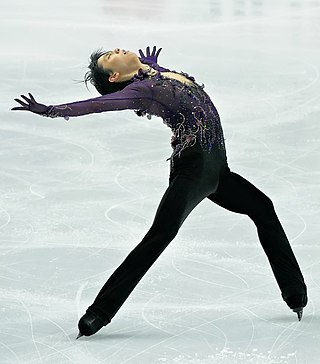

Figure skating is a sport in which individuals, pairs, or groups perform on figure skates on ice. It was the first winter sport to be included in the Olympic Games, when it was contested at the 1908 Olympics in London. The Olympic disciplines are men's singles, women's singles, pair skating, and ice dance; the four individual disciplines are also combined into a team event, which was first included in the Winter Olympics in 2014. The non-Olympic disciplines include synchronized skating, Theater on Ice, and four skating. From intermediate through senior-level competition, skaters generally perform two programs, which, depending on the discipline, may include spins, jumps, moves in the field, lifts, throw jumps, death spirals, and other elements or moves.

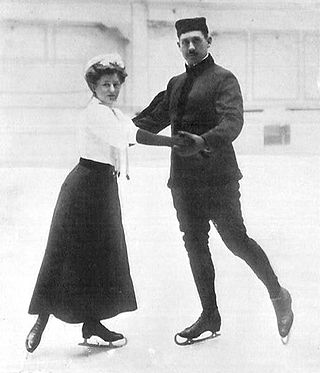

Ice dance is a discipline of figure skating that historically draws from ballroom dancing. It joined the World Figure Skating Championships in 1952, and became a Winter Olympic Games medal sport in 1976. According to the International Skating Union (ISU), the governing body of figure skating, an ice dance team consists of one woman and one man.

Figure skating jumps are an element of three competitive figure skating disciplines: men's singles, women's singles, and pair skating – but not ice dancing. Jumping in figure skating is "relatively recent". They were originally individual compulsory figures, and sometimes special figures; many jumps were named after the skaters who invented them or from the figures from which they were developed. It was not until the early part of the 20th century, well after the establishment of organized skating competitions, when jumps with the potential of being completed with multiple revolutions were invented and when jumps were formally categorized. In the 1920s Austrian skaters began to perform the first double jumps in practice. Skaters experimented with jumps, and by the end of the period, the modern repertoire of jumps had been developed. Jumps did not have a major role in free skating programs during international competitions until the 1930s. During the post-war period and into the 1950s and early 1960s, triple jumps became more common for both male and female skaters, and a full repertoire of two-revolution jumps had been fully developed. In the 1980s men were expected to complete four or five difficult triple jumps, and women had to perform the easier triples. By the 1990s, after compulsory figures were removed from competitions, multi-revolution jumps became more important in figure skating.

Spins are an element in figure skating in which the skater rotates, centered on a single point on the ice, while holding one or more body positions. They are performed by all disciplines of the sport, single skating, pair skating, and ice dance, and are a required element in most figure skating competitions. As The New York Times says, "While jumps look like sport, spins look more like art. While jumps provide the suspense, spins provide the scenery, but there is so much more to the scenery than most viewers have time or means to grasp". According to world champion and figure skating commentator Scott Hamilton, spins are often used "as breathing points or transitions to bigger things"

Molly house or molly-house was a term used in 18th- and 19th-century Britain for a meeting place for homosexual men. The meeting places were generally taverns, public houses, coffeehouses or even private rooms where men could either socialise or meet possible sexual partners.

Peggy Gale Fleming is an American former figure skater. She is the 1968 Olympic Champion in the ladies' singles, being the only American gold medalist at these Games, and a three-time World Champion (1966–1968) in the same event. Fleming has been a television commentator in figure skating for over 20 years, including at several Winter Olympic Games.

Compulsory figures or school figures were formerly a segment of figure skating, and gave the sport its name. They are the "circular patterns which skaters trace on the ice to demonstrate skill in placing clean turns evenly on round circles". For approximately the first 50 years of figure skating as a sport, until 1947, compulsory figures made up 60 percent of the total score at most competitions around the world. These figures continued to dominate the sport, although they steadily declined in importance, until the International Skating Union (ISU) voted to discontinue them as a part of competitions in 1990. Learning and training in compulsory figures instilled discipline and control; some in the figure skating community considered them necessary to teach skaters basic skills. Skaters would train for hours to learn and execute them well, and competing and judging figures would often take up to eight hours during competitions.

Richard Totten Button is an American former figure skater and skating analyst. He is a two-time Olympic champion and five-time consecutive World champion (1948–1952). He is also the only non-European man to have become European champion. Button is credited as having been the first skater to successfully land the double Axel jump in competition in 1948, as well as the first triple jump of any kind – a triple loop – in 1952. He also invented the flying camel spin, which was originally known as the "Button camel". He "brought increased athleticism" to figure skating in the years following World War II.

The Salchow jump is an edge jump in figure skating. It was named after its inventor, Ulrich Salchow, in 1909. The Salchow is accomplished with a takeoff from the back inside edge of one foot and a landing on the back outside edge of the opposite foot. It is "usually the first jump that skaters learn to double, and the first or second to triple". Timing is critical because both the takeoff and landing must be on the backward edge. A Salchow is deemed cheated if the skate blade starts to turn forward before the takeoff, or if it has not turned completely backward when the skater lands back on the ice.

The loop jump is an edge jump in the sport of figure skating. The skater executes it by taking off from the back outside edge of the skating foot, turning one rotation in the air, and landing on the back outside edge of the same foot. It is often performed as the second jump in a combination.

Special figures were a component of figure skating in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Like compulsory figures, special figures involved tracing patterns on the ice with the blade of one ice skate. This required the skater to display significant balance and control while skating on one foot.

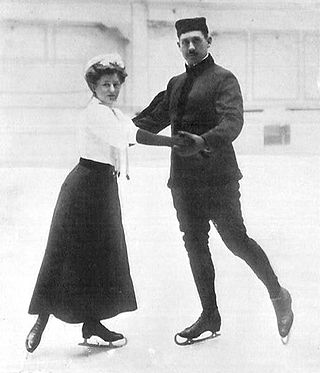

Pair skating is a figure skating discipline defined by the International Skating Union (ISU) as "the skating of two persons in unison who perform their movements in such harmony with each other as to give the impression of genuine Pair Skating as compared with independent Single Skating". The ISU also states that a pairs team consists of "one Woman and one Man". Pair skating, along with men's and women's single skating, has been an Olympic discipline since figure skating, the oldest Winter Olympic sport, was introduced at the 1908 Summer Olympics in London. The ISU World Figure Skating Championships introduced pair skating in 1908.

The camel spin is one of the three basic figure skating spin positions. British figure skater Cecilia Colledge was the first to perform it. The camel spin, for the first ten years after it was created, was performed mostly by women, although American skater Dick Button performed the first forward camel spin, a variation of the camel spin, and made it a regular part of the repertoire performed by male skaters. The camel spin is executed on one foot, and is an adaptation of the ballet pose the arabesque to the ice. When the camel spin is executed well, the stretch of the skater's body creates a slight arch or straight line. Skaters increase the difficulty of camel spins in a variety of ways.

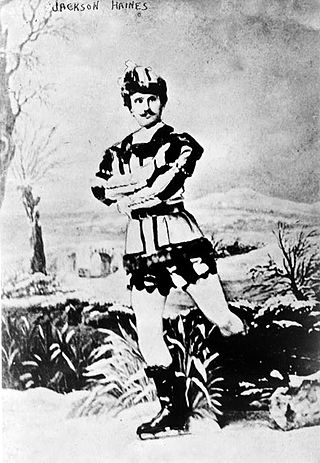

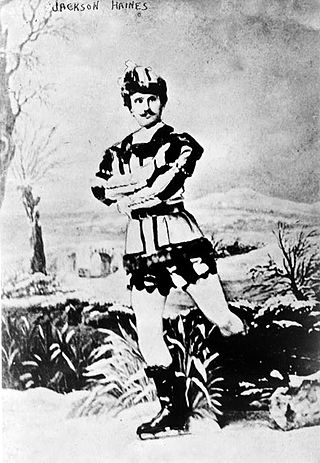

Jackson Haines (1840–1875) was an American ballet dancer and figure skater who is regarded as the father of modern figure skating.

The history of figure skating stretches back to prehistoric times. Primitive ice skates appear in the archaeological record from about 3000 BC. Edges were added by the Dutch in the 13th and 14th century. International figure skating competitions began appearing in the late 19th century; in 1891, the European Championships were inaugurated in Hamburg, Germany, and in 1896, the first World Championship were held in Saint Petersburg, Russian Empire. At the 1908 Summer Olympics in London, England, figure skating became the first winter sport to be included in the Olympics.

Single skating is a discipline of figure skating in which male and female skaters compete individually. Men's singles and women's singles are governed by the International Skating Union (ISU). Figure skating is the oldest winter sport contested at the Olympics, with men's and women's single skating appearing as two of the four figure skating events at the London Games in 1908.

The 6.0 system of judging figure skating was developed during the early days of the sport, when early international competitions consisted of only compulsory figures. Skaters performed each figure three times on each foot, for a total of six, which as writer Ellyn Kestnbaum states, "gave rise to the system of awarding marks based on a standard of 6.0 as perfection". It was used in competitive figure skating until 2004, when it was replaced by the ISU Judging System in international competitions, as a result of the 2002 Winter Olympics figure skating scandal. British ice dancers Jayne Torvill and Christopher Dean earned the most overall 6.0s in ice dance, Midori Ito from Japan has the most 6.0s in single skating, and Irina Rodnina from Russia, with two different partners, has the most 6.0s in pair skating.

The Fortune of War was an ancient public house in Smithfield, London. It was located on a corner originally known as 'Pie Corner', today at the junction of Giltspur Street and Cock Lane where the Golden Boy of Pye Corner resides, the name deriving from the magpie represented on the sign of an adjoining tavern. It is allegedly the place where the Great Fire of London stopped, after destroying a large part of the City of London in 1666. The statue of a cherub, the Golden Boy of Pye Corner, initially built in the front of the pub, commemorates the end of the fire.

The upright spin is one of the three basic figure skating spin positions. The International Skating Union (ISU), the governing body of figure skating, defines an upright spin as a spin with "any position with the skating leg extended or slightly bent which is not a camel position". It was invented by British figure skater Cecilia Colledge. Variations of the upright spin include the layback spin, the Biellmann spin, the full layback, the split, the back upright spin, the forward upright spin, the scratchspin, and the sideways leaning spin.