Related Research Articles

Jedediah Strong Smith was an American clerk, transcontinental pioneer, frontiersman, hunter, trapper, author, cartographer, mountain man and explorer of the Rocky Mountains, the Western United States, and the Southwest during the early 19th century. After 75 years of obscurity following his death, Smith was rediscovered as the American whose explorations led to the use of the 20-mile (32 km)-wide South Pass as the dominant route across the Continental Divide for pioneers on the Oregon Trail.

A mountain man is an explorer who lives in the wilderness and makes his living from hunting and trapping. Mountain men were most common in the North American Rocky Mountains from about 1810 through to the 1880s. They were instrumental in opening up the various emigrant trails allowing Americans in the east to settle the new territories of the far west by organized wagon trains traveling over roads explored and in many cases, physically improved by the mountain men and the big fur companies originally to serve the mule train-based inland fur trade.

William Henry Ashley was an American miner, land speculator, manufacturer, territorial militia general, politician, frontiersman, fur trader, entrepreneur, hunter, and slave owner. Ashley was best known for being the co-owner with Andrew Henry of the highly-successful Rocky Mountain Fur Incorporated, otherwise known as "Ashley's Hundred" for the famous mountain men working for the firm from 1822 to 1834.

David Edward “Davey” Jackson was an American pioneer, trapper, fur trader, and explorer.

Major Andrew Henry was an American miner, army officer, frontiersman, trapper and entrepreneur. Alongside William H. Ashley, Henry was the co-owner of the successful Rocky Mountain Fur Company, otherwise known as "Ashley's Hundred", for the famous mountain men working for their firm from 1822 to 1832. Henry appears in the narrative poem the Song of Hugh Glass, which is part of the Neihardt's Cycle of the West. He is portrayed by John Huston in the 1971 film Man in the Wilderness and by Domhnall Gleeson in the 2015 film The Revenant, both of which depict Glass's bear attack and journey.

Caleb Greenwood was a Western U.S. fur trapper and trail guide.

William Lewis Sublette, also spelled Sublett, was an American frontiersman, trapper, fur trader, explorer, and mountain man. After 1823, he became an agent of the Rocky Mountain Fur Company, along with his four brothers. Later he became one of the company's co-owners, utilizing the riches of the Oregon Country. He helped settle and improve the best routes for migrants along the Oregon Trail.

Osborne Russell was a mountain man and politician who helped form the government of the U.S. state of Oregon. He was born in Maine.

Thomas Fitzpatrick was an Irish-American fur trader, Indian agent, and mountain man. He trapped for the Rocky Mountain Fur Company and the American Fur Company. He was among the first white men to discover South Pass, Wyoming. In 1831, he found and took in a lost Arapaho boy, Friday, who he had schooled in St. Louis, Missouri; Friday became a noted interpreter and peacemaker and leader of a band of Northern Arapaho.

Robert Campbell was an Irish immigrant who became an American frontiersman, fur trader and businessman. His St. Louis home is now preserved as a museum; the Campbell House Museum.

Étienne Provost was a Canadian fur trader whose trapping and trading activities in the American southwest preceded Mexican independence. He was also known as Proveau and Provot. Leading a company headquartered in Taos, in what is today New Mexico, he was active in the Green River drainage and the central portion of modern Utah. He was one of the first people of European descent to see the Great Salt Lake, purportedly reaching its shores around 1824–25. However, Jim Bridger also reached the lake at about the same time, in late 1824, and maps from the 1600s may show the Great Salt Lake, possibly indicating European explorers reached the area over a century before Provost or Bridger.

Pierre's Hole is a shallow valley in the western United States in eastern Idaho, just west of the Teton Range in Wyoming. At an elevation over 6,000 feet (1,830 m) above sea level, it collects the headwaters of the Teton River, and was a strategic center of the fur trade of the northern Rocky Mountains. The nearby Jackson's Hole area in Wyoming is on the opposite side of the Tetons.

John Henry Weber (1779–1859) was an American fur trader and explorer. Weber was active in the early years of the fur trade, exploring territory in the Rocky Mountains and areas in the current state of Utah. The Weber River, Weber State University, and Weber County, Utah were named for Weber.

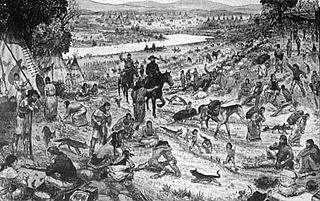

The Rocky Mountain Rendezvous was an annual rendezvous, held between 1825 and 1840 at various locations, organized by a fur trading company at which trappers and mountain men sold their furs and hides and replenished their supplies. The fur companies assembled teamster-driven mule trains which carried whiskey and supplies to a pre-announced location each spring-summer and set up a trading fair. At the end of the rendezvous, the teamsters packed the furs out, either to Fort Vancouver in the Pacific Northwest for the British companies or to one of the northern Missouri River ports such as St. Joseph, Missouri, for American companies. Early explorer and trader Jacques La Ramee organized a group of independent free trappers to the first ever gathering as early as 1815 at the junction of the North Platte and Laramie Rivers after befriending numerous native American tribes.

The Missouri Fur Company was one of the earliest fur trading companies in St. Louis, Missouri. Dissolved and reorganized several times, it operated under various names from 1809 until its final dissolution in 1830. It was created by a group of fur traders and merchants from St. Louis and Kaskaskia, Illinois, including Manuel Lisa and members of the Chouteau family. Its expeditions explored the upper Missouri River and traded with a variety of Native American tribes, and it acted as the prototype for fur trading companies along the Missouri River until the 1820s.

The fur trade in Montana was a major period in the area's economic history from about 1800 to the 1850s. It also represents the initial meeting of cultures between indigenous peoples and those of European ancestry. British and Canadian traders approached the area from the north and northeast focusing on trading with the indigenous people, who often did the trapping of beavers and other animals themselves. American traders moved gradually up the Missouri River seeking to beat British and Canadian traders to the profitable Upper Missouri River region.

Hiram Scott (1805–1828) was an American mountain man, trapper, and pelt trader who trapped and took part in expeditions throughout the western United States during the 1820s. Born in Missouri, Scott joined the Rocky Mountain Fur Company in 1822 and took part in the first fur trade expedition at the Great Salt Lake in Utah. He died at age 23 near a cliff along the North Platte River in Nebraska which was named in his honor. The circumstances leading to his demise have given rise to many diverse accounts and theories.

Henry Fraeb, also called Frapp, was a mountain man, fur trader, and trade post operator of the American West, operating in the present-day states of Colorado, Wyoming, and Montana.

Moses Harris, also known as Black Harris, was a trapper, scout, guide, and mountain man. He participated in expeditions across the Continental Divide and to the Pacific Ocean through the Rocky and Cascade Mountains. He rescued westward-bound pioneers. Harris spoke the Shoshoni language.

Joseph Bijeau, also known as Joseph Bijeau dit Bissonet and Joseph Bissonet, was among the earliest fur trappers of the Rocky Mountains. He was a guide for Stephen Harriman Long's expedition of the Great Plains in 1820. A fur trapper and hunter, he lived among the Pawnee people. He was able to communicate to a number of Native American tribes through his use of sign language as well as the Crow language, which was used among a number of western tribes. After Spain lost the Mexican territory, trappers like Bijeau moved to Taos where they could trap, trade, and travel east without the hostilities that they experienced in the western United States.

References

- 1 2 3 Chittenden, Hiram Martin (1954). The American Fur Trade of the Far West: a History of the Pioneer Trading Posts and Early Fur Companies of the Missouri Valley and the Rocky Mountains and of the Overland Commerce with Santa Fe. Stanford, CA: Academic Reprints.

- ↑ Advertisement." St. Louis Enquirer (St. Louis, Missouri) III, no. 296, March 23, 1822: [4]. Readex: America's Historical Newspapers

- ↑ "Mountain Man Hugh Glass - the Real Story".

- ↑ Caesar, Gene (1961). "King of the Mountain Men". E.P. Dutton Co. pp. 22, 81–82, 103. Retrieved 18 April 2021.

- 1 2 Vestal, Stanley (1970). Jim Bridger; Mountain Man. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press. pp. 8, 13, 40, 68, 86, 103. ISBN 9780803257207.

- 1 2 3 Dolin, Eric Jay (2010). Fur, Fortune, and Empire: The Epic History of the Fur Trade in America. New York: W. W. Norton & Company, Inc. ISBN 9780393067101.

- ↑ Berry, Don (1961). A Majority of Scoundrels : an Informal History of the Rocky Mountain Fur Company. New York: Harper.

- ↑ Malone, Michael P.; Roeder, Richard B.; Lang, William L. (1991). Montana : a history of two centuries (Revised ed.). Seattle, WA: University of Washington Press. pp. 54–56.