The Roman legion, the largest military unit of the Roman army, comprised 4,200 infantry and 300 equites (cavalry) in the period of the Roman Republic and 5,600 infantry and 200 auxilia in the period of the Roman Empire.

The Romano-British culture arose in Britain under the Roman Empire following the Roman conquest in AD 43 and the creation of the province of Britannia. It arose as a fusion of the imported Roman culture with that of the indigenous Britons, a people of Celtic language and custom.

The Praetorian Guard was an elite unit of the Imperial Roman army that served as personal bodyguards and intelligence agents for the Roman emperors.

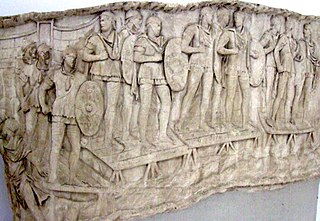

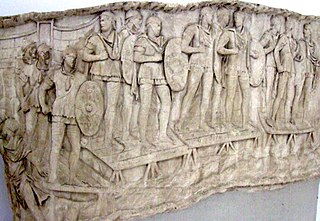

The Roman army was the armed forces deployed by the Romans throughout the duration of Ancient Rome, from the Roman Kingdom to the Roman Republic and the Roman Empire, and its medieval continuation, the Eastern Roman Empire. It is thus a term that may span approximately 2,205 years, during which the Roman armed forces underwent numerous permutations in size, composition, organisation, equipment and tactics, while conserving a core of lasting traditions.

The Constitutio Antoniniana, also called the Edict of Caracalla or the Antonine Constitution, was an edict issued in AD 212 by the Roman emperor Caracalla. It declared that all free men in the Roman Empire were to be given full Roman citizenship.

The Auxilia were introduced as non-citizen troops attached to the citizen legions by Augustus after his reorganisation of the Imperial Roman army from 27 BC. By the 2nd century, the Auxilia contained the same number of infantry as the legions and, in addition, provided almost all of the Roman army's cavalry and more specialised troops. The auxilia thus represented three-fifths of Rome's regular land forces at that time. Like their legionary counterparts, auxiliary recruits were mostly volunteers, not conscripts.

The structural history of the Roman military concerns the major transformations in the organization and constitution of ancient Rome's armed forces, "the most effective and long-lived military institution known to history." At the highest level of structure, the forces were split into the Roman army and the Roman navy, although these two branches were less distinct than in many modern national defense forces. Within the top levels of both army and navy, structural changes occurred as a result of both positive military reform and organic structural evolution. These changes can be divided into four distinct phases.

In the early Roman Empire, from 30 BC to AD 212, a peregrinus was a free provincial subject of the Empire who was not a Roman citizen. Peregrini constituted the vast majority of the Empire's inhabitants in the 1st and 2nd centuries AD. In AD 212, all free inhabitants of the Empire were granted citizenship by the Constitutio Antoniniana, with the exception of the dediticii, people who had become subject to Rome through surrender in war, and freed slaves.

The overall size of the Roman forces in Roman Britain grew from about 40,000 in the mid 1st century AD to a maximum of about 55,000 in the mid 2nd century. The proportion of auxiliaries in Britain grew from about 50% before 69 AD to over 70% in c. 150 AD. By the mid-2nd century, there were about 70 auxiliary regiments in Britain, for a total of over 40,000 men. These outnumbered the 16,500 legionaries in Britain by 2.5 to 1. This was the greatest concentration of auxilia in any single province of the Roman Empire. It implies major continuing security problems; this is supported by the (thin) historical evidence. After Agricola, the following emperors conducted major military operations in Britain: Hadrian, Antoninus Pius, Constantius I, and Septimius Severus.

Cohors quarta Aquitanorum equitata civium Romanorum was a Roman auxiliary mixed infantry and cavalry regiment. It was probably originally raised in the Julio-Claudian era, perhaps under Augustus after the subjugation of the Aquitani in 26 BC. Alternatively, it may have been raised in a later levy of Aquitani after 14 AD. Unlike most Gauls, the Aquitani were not Celtic-speaking but spoke Aquitanian, a now extinct non Indo-European language closely related to Basque. Some tribes in Aquitania were Celtic-speaking however, such as the Bituriges.

Cohors quinta Delmatarum civium Romanorum was a Roman auxiliary infantry regiment. It is named after the Dalmatae, an Illyrian-speaking tribe that inhabited the Adriatic coastal mountain range of the eponymous Dalmatia. The ancient geographer Strabo describes these mountains as extremely rugged, and the Dalmatae as backward and warlike. He claims that they did not use money long after their neighbours adopted it and that they "made war on the Romans for a long time". He also criticises the Dalmatae, a nation of pastoralists, for turning fertile plains into sheep pasture. Indeed, the name of the tribe itself is believed to mean "shepherds", derived from the Illyrian word delme ("sheep"). The final time this people fought against Rome was in the Illyrian revolt of AD 6–9. The revolt was started by Dalmatae auxiliary forces and soon spread all over Dalmatia and Pannonia. The resulting war was described by the Roman writer Suetonius as the most difficult faced by Rome since the Punic Wars two centuries earlier. But after the war, the Dalmatae became a loyal and important source of recruits for the Roman army.

This article concerns the Roman auxiliary regiments of the Principate period originally recruited in the western Alpine regions of the empire. The cohortes Alpinorum came from Tres Alpes, the three small Roman provinces of the western Alps, Alpes Maritimae, Alpes Cottiae and Alpes Graiae. The cohortes Ligurum were originally raised from the Ligures people of Alpes Maritimae and Liguria regio of NW Italia.

In ancient Rome, the dediticii or peregrini dediticii were a class of free provincials who were neither slaves nor citizens holding either full Roman citizenship as cives or Latin rights as Latini.

The equites singulares Augusti were the cavalry arm of the Praetorian Guard during the Principate period of imperial Rome. Based in Rome, they escorted the Roman emperor whenever he left the city on a campaign or on tours of the provinces. The equites singulares Augusti were a highly trained unit dedicated to protecting the emperor. Men who served in the equites singulares Augusti held a Roman public status as equites.

The Imperial Roman army was the military land force of the Roman Empire from 27 BC to 476 AD, and the final incarnation in the long history of the Roman army. This period is sometimes split into the Principate and the Dominate (284–476) periods.

The Cohors IV Tungrorum mill eq was an Auxiliary cohort of the Roman Army based in Abusina during the second century. It had a strength of 1040 soldiers.

The honesta missio was the honorable discharge from the military service in the Roman Empire. The status conveyed particular privileges. Among other things, an honorably discharged legionary was paid discharge money from a treasury established by Augustus, the aerarium militare, which amounted to 12,000 sesterces for the common soldier and around 600,000 sesterces for the primus pilus until the Principate of Caracalla.

Margaret Roxan (1924–2003) was a British archaeologist and expert on Roman military diplomas. Her major contribution to the discipline was three edited collections of newly-found diplomas that acquired a scholarly authority and place as the direct successor of Theodor Mommsen and Herbert Nesselhauf. She also edited the diplomas for publication in The Roman Inscriptions of Britain.

The Cohors II Lucensium [equitata] was a Roman auxiliary unit. It is attested by military diplomas and inscriptions.