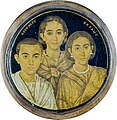

A portrait is a painting, photograph, sculpture, or other artistic representation of a person, in which the face not always is predominant. In arts portrait can be represented as half body and even full body. If the subject in full body better represents personality and mood - this type of presentation can be chosen. The intent is to display the likeness, personality, and even the mood of the person. For this reason, in photography a portrait is generally not a snapshot, but a composed image of a person in a still position. A portrait often shows a person looking directly at the painter or photographer, to most successfully engage the subject with the viewer, but portrait can be represented as a profile and 3/4. It’s important to understand that a subject with eyes closed also can be tractate as a portrait.

Ancient art refers to the many types of art produced by the advanced cultures of ancient societies with different forms of writing, such as those of ancient China, India, Mesopotamia, Persia, Palestine, Egypt, Greece, and Rome. The art of pre-literate societies is normally referred to as prehistoric art and is not covered here. Although some pre-Columbian cultures developed writing during the centuries before the arrival of Europeans, on grounds of dating these are covered at pre-Columbian art and articles such as Maya art, Aztec art, and Olmec art.

The art of Ancient Rome, and the territories of its Republic and later Empire, includes architecture, painting, sculpture and mosaic work. Luxury objects in metal-work, gem engraving, ivory carvings, and glass are sometimes considered to be minor forms of Roman art, although they were not considered as such at the time. Sculpture was perhaps considered as the highest form of art by Romans, but figure painting was also highly regarded. A very large body of sculpture has survived from about the 1st century BC onward, though very little from before, but very little painting remains, and probably nothing that a contemporary would have considered to be of the highest quality.

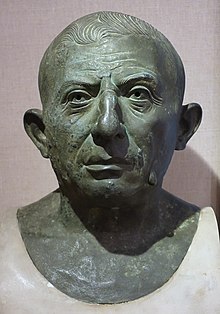

A bust is a sculpted or cast representation of the upper part of the human body, depicting a person's head and neck, and a variable portion of the chest and shoulders. The piece is normally supported by a plinth. The bust is generally a portrait intended to record the appearance of an individual, but may sometimes represent a type. They may be of any medium used for sculpture, such as marble, bronze, terracotta, plaster, wax or wood.

The National Archaeological Museum of Naples is an important Italian archaeological museum, particularly for ancient Roman remains. Its collection includes works from Greek, Roman and Renaissance times, and especially Roman artifacts from the nearby Pompeii, Stabiae and Herculaneum sites. From 1816 to 1861, it was known as Real Museo Borbonico.

The Glyptothek is a museum in Munich, Germany, which was commissioned by the Bavarian King Ludwig I to house his collection of Greek and Roman sculptures. It was designed by Leo von Klenze in the neoclassical style, and built from 1816 to 1830. Today the museum is a part of the Kunstareal.

The sculpture of ancient Greece is the main surviving type of fine ancient Greek art as, with the exception of painted ancient Greek pottery, almost no ancient Greek painting survives. Modern scholarship identifies three major stages in monumental sculpture in bronze and stone: the Archaic, Classical (480–323) and Hellenistic. At all periods there were great numbers of Greek terracotta figurines and small sculptures in metal and other materials.

Verism was a realistic style in Roman art. It principally occurred in portraiture of politicians, whose imperfections of the face were exacerbated in order to highlight their old age and gravitas. The word comes from Latin verus (true).

Classical sculpture refers generally to sculpture from Ancient Greece and Ancient Rome, as well as the Hellenized and Romanized civilizations under their rule or influence, from about 500 BC to around 200 AD. It may also refer more precisely a period within Ancient Greek sculpture from around 500 BC to the onset of the Hellenistic style around 323 BC, in this case usually given a capital "C". The term "classical" is also widely used for a stylistic tendency in later sculpture, not restricted to works in a Neoclassical or classical style.

The study of Roman sculpture is complicated by its relation to Greek sculpture. Many examples of even the most famous Greek sculptures, such as the Apollo Belvedere and Barberini Faun, are known only from Roman Imperial or Hellenistic "copies". At one time, this imitation was taken by art historians as indicating a narrowness of the Roman artistic imagination, but, in the late 20th century, Roman art began to be reevaluated on its own terms: some impressions of the nature of Greek sculpture may in fact be based on Roman artistry.

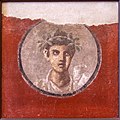

The Pompeian Styles are four periods which are distinguished in ancient Roman mural painting. They were originally delineated and described by the German archaeologist August Mau (1840–1909) from the excavation of wall paintings at Pompeii, which is one of the largest groups of surviving Roman frescoes.

Gamzigrad is an archaeological site, spa resort and UNESCO World Heritage Site of Serbia, located south of the Danube river, in the city of Zaječar. It is the location of the ancient Roman complex of palaces and temples Felix Romuliana, built by Emperor Galerius in Dacia Ripensis. The main area covers 10 acres (40,000 m2).

Hellenistic art is the art of the Hellenistic period generally taken to begin with the death of Alexander the Great in 323 BC and end with the conquest of the Greek world by the Romans, a process well underway by 146 BC, when the Greek mainland was taken, and essentially ending in 30 BC with the conquest of Ptolemaic Egypt following the Battle of Actium. A number of the best-known works of Greek sculpture belong to this period, including Laocoön and His Sons, Venus de Milo, and the Winged Victory of Samothrace. It follows the period of Classical Greek art, while the succeeding Greco-Roman art was very largely a continuation of Hellenistic trends.

The Portrait of the Four Tetrarchs is a porphyry sculpture group of four Roman emperors dating from around 300 AD. The sculptural group has been fixed to a corner of the façade of St Mark's Basilica in Venice, Italy since the Middle Ages. It probably formed part of the decorations of the Philadelphion in Constantinople, and was removed to Venice in 1204 or soon after.

Heroic nudity or ideal nudity is a concept in classical scholarship to describe the un-realist use of nudity in classical sculpture to show figures who may be heroes, deities, or semi-divine beings. This convention began in Archaic and Classical Greece and continued in Hellenistic and Roman sculpture. The existence or place of the convention is the subject of scholarly argument.

In classical antiquity, the muscle cuirass, anatomical cuirass, or heroic cuirass is a type of cuirass made to fit the wearer's torso and designed to mimic an idealized male human physique. It first appears in late Archaic Greece and became widespread throughout the 5th and 4th centuries BC. Originally made from hammered bronze plate, boiled leather also came to be used. It is commonly depicted in Greek and Roman art, where it is worn by generals, emperors, and deities during periods when soldiers used other types.

A Roman mosaic is a mosaic made during the Roman period, throughout the Roman Republic and later Empire. Mosaics were used in a variety of private and public buildings, on both floors and walls, though they competed with cheaper frescos for the latter. They were highly influenced by earlier and contemporary Hellenistic Greek mosaics, and often included famous figures from history and mythology, such as Alexander the Great in the Alexander Mosaic.

Ancient Greek art stands out among that of other ancient cultures for its development of naturalistic but idealized depictions of the human body, in which largely nude male figures were generally the focus of innovation. The rate of stylistic development between about 750 and 300 BC was remarkable by ancient standards, and in surviving works is best seen in sculpture. There were important innovations in painting, which have to be essentially reconstructed due to the lack of original survivals of quality, other than the distinct field of painted pottery.

Roman Republican art is the artistic production that took place in Roman territory during the period of the Republic, conventionally from 509 BC to 27 BC.

The Palazzo Massimo alle Terme is the main of the four sites of the Roman National Museum, along with the original site of the Baths of Diocletian, which currently houses the epigraphic and protohistoric section, Palazzo Altemps, home to the Renaissance collections of ancient sculpture, and the Crypta Balbi, home to the early medieval collection.