Related Research Articles

Espionage, spying, or intelligence gathering is the act of obtaining secret or confidential information (intelligence). A person who commits espionage is called an espionage agent or spy. Any individual or spy ring, in the service of a government, company, criminal organization, or independent operation, can commit espionage. The practice is clandestine, as it is by definition unwelcome. In some circumstances, it may be a legal tool of law enforcement and in others, it may be illegal and punishable by law.

William John Burns was an American private investigator and law enforcement official. He was known as "America's Sherlock Holmes" and earned fame for having conducted private investigations into a number of notable incidents, such as clearing Leo Frank of the 1913 murder of Mary Phagan, and for investigating the deadly 1910 Los Angeles Times bombing conducted by members of the International Association of Bridge, Structural, Ornamental and Reinforcing Iron Workers. From August 22, 1921, to May 10, 1924, Burns served as the director of the Bureau of Investigation (BOI), predecessor to the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI).

William G. Sebold was a United States citizen who was coerced into becoming a spy when he visited Germany after being pressured by several high-ranking Nazi members. He informed the American Consul General in Cologne before leaving Germany and became a double agent for the FBI. With the assistance of another German agent, Fritz Duquesne, he recruited 33 agents that became known as the Duquesne Spy Ring. In June 1941, the Federal Bureau of Investigation arrested all of the agents. They were convicted and sentenced to a total of 300 years in prison.

Elizabeth Terrill Bentley was an American NKVD spymaster, who was recruited from within the Communist Party USA (CPUSA). She served the Soviet Union as the primary handler of multiple highly placed moles within both the United States Federal Government and the Office of Strategic Services from 1938 to 1945. After being rendered bereft by the 1943 death of her lover, NKVD New York City station chief Jacob Golos, a heartbroken Bentley defected by contacting the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) and debriefing about her own espionage activities.

George John Dasch was a German agent who landed on American soil during World War II. He helped to destroy Nazi Germany's espionage program in the United States by defecting to the American cause, but was tried and convicted of espionage.

The Lawrence Franklin espionage scandal involved Lawrence Franklin passing classified documents regarding United States policy towards Iran to Israel. Franklin, a former United States Department of Defense employee, pleaded guilty to several espionage-related charges and was sentenced in January 2006 to nearly 13 years of prison, which was later reduced to ten months' house arrest. Franklin passed information to American Israel Public Affairs Committee policy director Steven Rosen and AIPAC senior Iran analyst Keith Weissman, who were fired by AIPAC. They were then indicted for illegally conspiring to gather and disclose classified national security information to Israel. However, prosecutors later dropped all charges against them without any plea bargain.

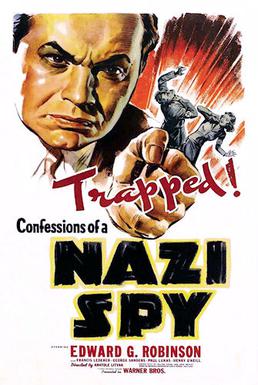

Confessions of a Nazi Spy is a 1939 American spy political thriller film directed by Anatole Litvak for Warner Bros. It was the first explicitly anti-Nazi film to be produced by a major Hollywood studio, being released in May 1939, four months before the beginning of World War II and two and a half years before the United States' entry into the war.

Richard W. Miller was an American FBI agent who was the first FBI agent indicted for and convicted of espionage. In 1991, he was sentenced to 20 years in prison but was freed after serving fewer than three years.

Brian Patrick Regan is a former master sergeant in the United States Air Force who was convicted of offering to sell secret information to foreign governments.

This page is a timeline of published security lapses in the United States government. These lapses are frequently referenced in congressional and non-governmental oversight. This article does not attempt to capture security vulnerabilities.

The Duquesne Spy Ring is the largest espionage case in the United States history that ended in convictions. A total of 33 members of a Nazi German espionage network headed by Frederick "Fritz" Joubert Duquesne were convicted after a lengthy investigation by the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI). Of those indicted, 19 pleaded guilty. The remaining 14 were brought to jury trial in Federal District Court, Brooklyn, New York, on September 3, 1941; all were found guilty on December 13, 1941. On January 2, 1942, the group members were sentenced to serve a total of over 300 years in prison.

David Sheldon Boone is a former U.S. Army signals analyst who worked for the National Security Agency (NSA) and was convicted of espionage-related charges in 1999 related to his sale of secret documents to the Soviet Union from 1988 to 1991. Boone's case was an example of a late Cold War U.S. government security breach.

Ben-Ami Kadish was a former U.S. Army mechanical engineer. He pleaded guilty in December 2008 to being an "unregistered agent for Israel," and admitted to disclosing classified U.S. documents to Israel in the 1980s. His unauthorized disclosure of classified U.S. secrets to Israel was concurrent with the espionage activity of Jonathan Pollard, who was convicted of espionage and answered to the same Israeli handler.

Rhodri Jeffreys-Jones is professor of American history emeritus and an honorary fellow in History at the University of Edinburgh, Scotland. He is an authority on American intelligence history, having written two American intelligence history surveys and studies of the CIA and FBI. He has also written books on women and American foreign policy, America and the Vietnam War, and American labor history.

Manuel Sorola He was the first Hispanic agent with the FBI; hired in 1916. He joined the El Paso office as a special agent in 1922 and served in field offices in Brownsville, Phoenix, New Orleans and Los Angeles. Placed on limited duty in 1938, he continued to serve in the Los Angeles field office as a liaison to local law enforcement agencies until his retirement on January 31, 1949. He died in Los Angeles, California and is buried at Holy Cross Cemetery, Culver City.

Jessie Jordan was a Scottish hairdresser who was found guilty of spying for the German Abwehr on the eve of World War II. She had married again after her German husband died fighting for Germany, before she became a spy in Scotland. She was imprisoned and deported to Germany after the war ended.

Dr. Ignatz Theodor Griebl (1899–?) was a prominent German-American physician who is known as a recruiter for the German spy network in New York City in the era of the Nazi rise to power and buildup to World War II.

Leon George Turrou was an American special agent and translator with the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) tasked with leading an investigation that located and interrogated Nazi German spies within the United States. He also became the author of a popular book called Nazi Spies in America. His writings were adapted into the 1939 film Confessions of a Nazi Spy.

Charles A. Appel, Jr., known as the founder of the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) Laboratory, was an FBI Special Agent from 1924 through 1948. Assigned in 1929 by then-Bureau of Investigation Director J. Edgar Hoover to coordinate outside experts for forensic examinations, Appel became the Bureau’s one-man forensic laboratory in 1931. In November 1932, the FBI’s Technical Laboratory was formally established. In August 1933, he began processing evidence and testifying on handwriting, typewriting, fingerprints, ballistics, and chemicals submitted by U.S. police agencies. Appel was joined in late 1933 by Special Agent Samuel F. Pickering, a chemist, and in 1934, by Special Agents Ivan W. Conrad and Donald J. Parsons, also scientists. In September 1934, the FBI Laboratory came to widespread attention due to Appel’s identification of Bruno Hauptmann as the kidnapper of Charles Lindbergh Jr., from hand-written ransom demand notes.

References

- 1 2 "German Agent to Tell Story". Arizona Republic. UP. October 17, 1938. p. 2 – via Newspapers.com.

- ↑ "Rumrich Tells Plan to Forge F.D.'s Name". The Leaf-Chronicle. AP. October 19, 1938. p. 1 – via Newspapers.com.

- 1 2 Jeffreys-Jones, Rhodri (2007). The FBI: A History (Ebook). Yale University Press. pp. 144–149. ISBN 978-0-300-13887-0.

- 1 2 3 Bragman, Bob (December 7, 2016). "Old Mission Street Coca-Cola Bottling Plant once unwittingly employed Nazi spy". San Francisco Chronicle.

- ↑ Batvinis, Raymond J. (2007). The Origins of FBI Counterintelligence. University Press of Kansas. p. 6. ISBN 978-0-7006-1495-0.

- ↑ "Trial of Four as Nazi Spies Put Underway". The Brooklyn Citizen. October 14, 1938. p. 1 – via Newspapers.com.

- ↑ "Rumrich Testifies Spies Checked East Coast". Princeton Daily Clarion. UP. October 18, 1938. p. 1 – via Newspapers.com.

- ↑ "Rumrich Tells of Furnishing Code Book to Germans". The Daily Times. October 20, 1938. p. 1 – via Newspapers.com.

- 1 2 "Rumrich Nazi Spy Case". FBI. Retrieved March 17, 2023.

- ↑ Poveda, Tony G.; Rosenfeld, Susan; Powers, Richard Gid (1999). Athan Theoharis (ed.). The FBI: A Comprehensive Reference Guide. Oryx Press. pp. 58–59. ISBN 978-0-89774-991-6.

- ↑ Jeffreys-Jones, Rhodri (September 2020). "A Forgotten Scandal: How the Nazi Spy Case of 1938 Affected American Neutrality and German Diplomatic Opinion" (PDF). Passport. The Society for Historians of American Foreign Relations: 45–48. Retrieved March 17, 2023.