The Safavid dynasty was one of Iran's most significant ruling dynasties reigning from 1501 to 1736. Their rule is often considered the beginning of modern Iranian history, as well as one of the gunpowder empires. The Safavid Shāh Ismā'īl I established the Twelver denomination of Shīʿa Islam as the official religion of the Persian Empire, marking one of the most important turning points in the history of Islam. The Safavid dynasty had its origin in the Safavid order of Sufism, which was established in the city of Ardabil in the Iranian Azerbaijan region. It was an Iranian dynasty of Kurdish origin, but during their rule they intermarried with Turkoman, Georgian, Circassian, and Pontic Greek dignitaries, nevertheless, for practical purposes, they were Turkic-speaking and Turkified. From their base in Ardabil, the Safavids established control over parts of Greater Iran and reasserted the Iranian identity of the region, thus becoming the first native dynasty since the Sasanian Empire to establish a national state officially known as Iran.

Tahmasp I was the second shah of Safavid Iran from 1524 until his death in 1576. He was the eldest son of Ismail I and his principal consort, Tajlu Khanum. Ascending the throne after the death of his father on 23 May 1524, the first years of Tahmasp's reign were marked by civil wars between the Qizilbash leaders until 1532, when he asserted his authority and began an absolute monarchy. He soon faced a long-lasting war with the Ottoman Empire, which was divided into three phases. The Ottoman sultan, Suleiman the Magnificent, tried to install his own candidates on the Safavid throne. The war ended with the Peace of Amasya in 1555, with the Ottomans gaining sovereignty over Iraq, much of Kurdistan, and western Georgia. Tahmasp also had conflicts with the Uzbeks of Bukhara over Khorasan, with them repeatedly raiding Herat. In 1528, at the age of fourteen, he defeated the Uzbeks in the Battle of Jam by using artillery.

A talar or talaar is a type of porch or hall in Iranian architecture. It generally refers to a porch fronting a building, supported by columns, and open on one or three sides. The term is also applied more widely to denote a throne hall or audience hall with some of these features.

Kamāl ud-Dīn Behzād, also known as Kamal al-din Bihzad or Kamaleddin Behzād, was a Persian painter and head of the royal ateliers in Herat and Tabriz during the late Timurid and early Safavid Periods. He is regarded as marking the highpoint of the great tradition of Islamic miniature painting. He was well known for his very prominent role as kitābdār in the Herat Academy as well as his position in the Royal Library in the city of Herat. His art is unique in that it includes the common geometric attributes of Persian painting, while also inserting his own style, such as vast empty spaces to which the subject of the painting dances around. His art includes masterful use of value and individuality of character, with one of his most famous pieces being "The Seduction of Yusuf" from Sa'di's Bustan of 1488. Behzād's fame and renown in his lifetime inspired many during, and after, his life to copy his style and works due to the wide praise they received. Due to the great number of copies and difficulty with tracing origin of works, there is a large amount of contemporary work into proper attribution.

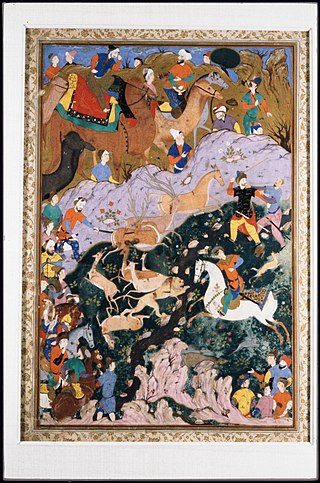

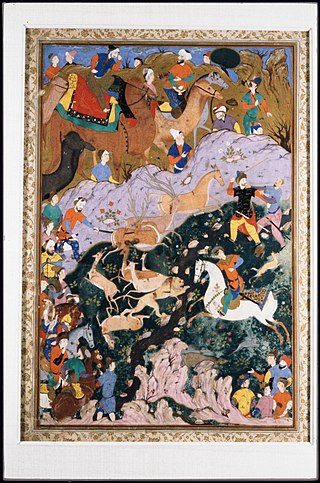

A Persian miniature is a small Persian painting on paper, whether a book illustration or a separate work of art intended to be kept in an album of such works called a muraqqa. The techniques are broadly comparable to the Western Medieval and Byzantine traditions of miniatures in illuminated manuscripts. Although there is an equally well-established Persian tradition of wall-painting, the survival rate and state of preservation of miniatures is better, and miniatures are much the best-known form of Persian painting in the West, and many of the most important examples are in Western, or Turkish, museums. Miniature painting became a significant genre in Persian art in the 13th century, receiving Chinese influence after the Mongol conquests, and the highest point in the tradition was reached in the 15th and 16th centuries. The tradition continued, under some Western influence, after this, and has many modern exponents. The Persian miniature was the dominant influence on other Islamic miniature traditions, principally the Ottoman miniature in Turkey, and the Mughal miniature in the Indian sub-continent.

Farrukh Beg, also known as Farrukh Husayn, was a Persian miniature painter, who spent a bulk of his career in Safavid Iran and Mughal India, praised by Mughal Emperor Jahangir as "unrivaled in the age."

Safavid art is the art of the Iranian Safavid dynasty from 1501 to 1722, encompassing Iran and parts of the Caucasus and Central Asia. It was a high point for Persian miniatures, architecture and also included ceramics, metal, glass, and gardens. The arts of the Safavid period show a far more unitary development than in any other period of Iranian art. The Safavid Empire was one of the most significant ruling dynasties of Iran. They ruled one of the greatest Persian empires since the Muslim conquest of Persia, and with this, the empire produced numerous artistic accomplishments.

Vahshi Bafqi was a Persian poet of the Safavid era, considered to be one of the greatest of his generation.

Prince Ibrahim Mirza, Solṭān Ebrāhīm Mīrzā, in full Abu'l Fat'h Sultan Ibrahim Mirza was a Persian prince of the Safavid dynasty, who was a favourite of his uncle and father-in-law Shah Tahmasp I, but who was executed by Tahmasp's successor, the Shah Ismail II. Ibrahim is now mainly remembered as a patron of the arts, especially the Persian miniature. Although most of his library and art collection was apparently destroyed by his wife after his murder, surviving works commissioned by him include the manuscript of the Haft Awrang of the poet Jami which is now in the Freer Gallery of Art in Washington D.C.

Aliquli Jabbadar was an Iranian artist, one of the first to have incorporated European influences in the traditional Safavid-era miniature painting. He is known for his scenes of the Safavid courtly life, especially his careful rendition of the physical setting and of details of dress.

Mo'en Mosavver or Mu‘in Musavvir was a Persian miniaturist, one of the significant in 17th-century Safavid Iran. Not much is known about the personal life of Mo'en, except that he was born in ca. 1610-1615, became a pupil of Reza Abbasi, the leading painter of the day, and probably died in 1693. Over 300 miniatures and drawings attributed to him survive. He was a conservative painter who partly reversed the advanced style of his master, avoiding influences from Western painting. However, he painted a number of scenes of ordinary people, which are unusual in Persian painting.

Safavid Iran or Safavid Persia, also referred to as the Safavid Empire, was one of the largest and long-standing Iranian empires after the 7th-century Muslim conquest of Persia, which was ruled from 1501 to 1736 by the Safavid dynasty. It is often considered the beginning of modern Iranian history, as well as one of the gunpowder empires. The Safavid Shāh Ismā'īl I established the Twelver denomination of Shīʿa Islam as the official religion of the empire, marking one of the most important turning points in the history of Islam.

Persian art or Iranian art has one of the richest art heritages in world history and has been strong in many media including architecture, painting, weaving, pottery, calligraphy, metalworking and sculpture. At different times, influences from the art of neighbouring civilizations have been very important, and latterly Persian art gave and received major influences as part of the wider styles of Islamic art. This article covers the art of Persia up to 1925, and the end of the Qajar dynasty; for later art see Iranian modern and contemporary art, and for traditional crafts see arts of Iran. Rock art in Iran is its most ancient surviving art. Iranian architecture is covered at that article.

The Shahnameh of Shah Tahmasp or Houghton Shahnameh is one of the most famous illustrated manuscripts of the Shahnameh, the national epic of Greater Iran, and a high point in the art of the Persian miniature. It is probably the most fully illustrated manuscript of the text ever produced. When created, the manuscript contained 759 pages, 258 of which were miniatures. These miniatures were hand-painted by the artists of the royal workshop in Tabriz under rulers Shah Ismail I and Shah Tahmasp I. Upon its completion, the Shahnameh was gifted to Ottoman Sultan Selim II in 1568. The page size is about 48 x 32 cm, and the text written in Nastaʿlīq script of the highest quality. The manuscript was broken up in the 1970s and pages are now in a number of different collections around the world.

Gülru Necipoğlu is a Turkish American professor of Islamic Art/Architecture. She has been the Aga Khan Professor and Director of the Aga Khan Program for Islamic Architecture at Harvard University since 1993, where she started teaching as Assistant Professor in 1987. She received her Harvard Ph.D. in the Department of History of Art and Architecture (1986), her BA in Art History at Wesleyan, her high school degree in Robert College, Istanbul (1975). She is married to the Ottoman historian and Harvard University professor Cemal Kafadar. Her sister is the historian Nevra Necipoğlu.

Dengiz Beg Rumlu was an Iranian courtier, who served as merchant-envoy to Habsburg Spain during the reign of Safavid king (shah) Abbas I.

Farangi-Sazi was a style of Persian painting that originated in Safavid Iran in the second half of the 17th century. This style of painting emerged during the reign of Shah Abbas II, but first became prominent under Shah Solayman I.

Ali Asghar was an Iranian court painter of the Safavid era. He was the father of the renowned miniaturist Reza Abbasi, whose early works were probably influenced by Ali Asghar.

'Ataullah Rushdi bin Ahmad Ma'mar was a 17th-century architect and a mathematics writer from the Mughal Empire of present-day India. He designed the Bibi Ka Maqbara at Aurangabad and some buildings at Shahjahanabad. As a mathematics writer, he translated the Arabic-language Khulasat al-Hisab and the Sanskrit-language Bijaganita into Persian.

Varka and Golshah, also Varqeh and Gulshah, Varqa o Golšāh, is an 11th-century Persian epic in 2,250 verses, written by the poet Ayyuqi. In the introduction, the author eulogized the famous Ghaznavid ruler Mahmud of Ghazni (r.998–1030).