The end zone is the scoring area on the field, according to gridiron-based codes of football. It is the area between the end line and goal line bounded by the sidelines. There are two end zones, each being on an opposite side of the field. It is bordered on all sides by a white line indicating its beginning and end points, with orange, square pylons placed at each of the four corners as a visual aid. Canadian rule books use the terms goal area and dead line instead of end zone and end line respectively, but the latter terms are the more common in colloquial Canadian English. Unlike sports like association football and ice hockey which require the ball/puck to pass completely over the goal line to count as a score, both Canadian and American football merely need any part of the ball to break the vertical plane of the outer edge of the goal line.

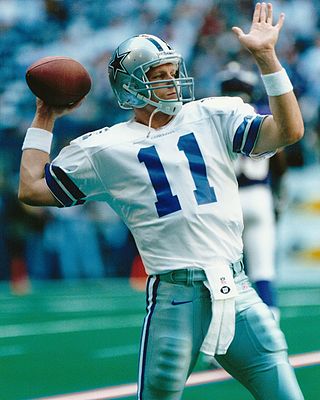

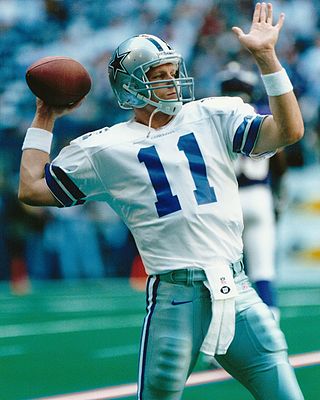

The quarterback, colloquially known as the "signal caller", is a position in gridiron football. Quarterbacks are members of the offensive platoon and mostly line up directly behind the offensive line. In modern American football, the quarterback is usually considered the leader of the offense, and is often responsible for calling the play in the huddle. The quarterback also touches the ball on almost every offensive play, and is almost always the offensive player that throws forward passes. When the QB is tackled behind the line of scrimmage, it is called a sack.

A touchdown is a scoring play in gridiron football. Whether running, passing, returning a kickoff or punt, or recovering a turnover, a team scores a touchdown by advancing the ball into the opponent's end zone. In American football, a touchdown is worth six points and is followed by an extra point or two-point conversion attempt.

A free kick is an action used in several codes of football to restart play with the kicking of a ball into the field of play.

Gridiron football, also known as North American football, or in North America as simply football, is a family of football team sports primarily played in the United States and Canada. American football, which uses 11 players, is the form played in the United States and the best known form of gridiron football worldwide, while Canadian football, which uses 12 players, predominates in Canada. Other derivative varieties include arena football, flag football and amateur games such as touch and street football. Football is played at professional, collegiate, high school, semi-professional, and amateur levels.

In American football, a touchback is a ruling that is made and signaled by an official when the ball becomes dead on or behind a team's own goal line and the opposing team gave the ball the momentum, or impetus, to travel over or across the goal line but did not have possession of the ball when it became dead. Since the 2018 season, touchbacks have also been awarded in college football on kickoffs that end in a fair catch by the receiving team between its own 25-yard line and goal line. Such impetus may be imparted by a kick, pass, fumble, or in certain instances by batting the ball. A touchback is not a play, but a result of events that may occur during a play. A touchback is the opposite of a safety with regard to impetus since a safety is scored when the ball becomes dead in a team's end zone after that team — the team whose end zone it is — caused the ball to cross the goal line.

American and Canadian football are gridiron codes of football that are very similar; both have their origins partly in rugby football, but some key differences exist between the two codes.

In Canadian football, a single is a one-point score that is awarded for certain plays that involve the ball being kicked into the end zone and not returned from it.

Gameplay in American football consists of a series of downs, individual plays of short duration, outside of which the ball is dead or not in play. These can be plays from scrimmage – passes, runs, punts or field goal attempts – or free kicks such as kickoffs and fair catch kicks. Substitutions can be made between downs, which allows for a great deal of specialization as coaches choose the players best suited for each particular situation. During a play, each team should have no more than 11 players on the field, and each of them has specific tasks assigned for that specific play.

In gridiron football, clock management is an aspect of game strategy that focuses on the game clock and/or play clock to achieve a desired result, typically near the end of a match. Depending on the game situation, clock management may entail playing in a manner that either slows or quickens the time elapsed from the game clock, to either extend the match or hasten its end. When the desired outcome is to end the match quicker, it is analogous to "running out the clock" seen in many sports. Clock management strategies are a significant part of American football, where an elaborate set of rules dictates when the game clock stops between downs, and when it continues to run.

A kickoff is a method of starting a drive in gridiron football. Additionally, it may refer to a kickoff time, the scheduled time of the first kickoff of a game. Typically, a kickoff consists of one team – the "kicking team" – kicking the ball to the opposing team – the "receiving team". The receiving team is then entitled to return the ball, i.e., attempt to advance it towards the kicking team's end zone, until the player with the ball is tackled by the kicking team, goes out of bounds, scores a touchdown, or the play is otherwise ruled dead. Kickoffs take place at the start of each half of play, the beginning of overtime in some overtime formats, and after scoring plays.

High school football, also known as prep football, is gridiron football played by high school teams in the United States and Canada. It ranks among the most popular interscholastic sports in both countries, but its popularity is declining, partly due to risk of injury, particularly concussions. According to The Washington Post, between 2009 and 2019, participation in high school football declined by 9.1%. It is the basic level or step of tackle football.

A field goal (FG) is a means of scoring in gridiron football. To score a field goal, the team in possession of the ball must place kick, or drop kick, the ball through the goal, i.e., between the uprights and over the crossbar. The entire ball must pass through the vertical plane of the goal, which is the area above the crossbar and between the uprights or, if above the uprights, between their outside edges. American football requires that a field goal must only come during a play from scrimmage while Canadian football retains open field kicks and thus field goals may be scored at any time from anywhere on the field and by any player. The vast majority of field goals, in both codes, are placekicked. Drop-kicked field goals were common in the early days of gridiron football but are almost never attempted in modern times. A field goal may also be scored through a fair catch kick, but this is also extremely rare. In most leagues, a successful field goal awards three points.

The following terms are used in American football, both conventional and indoor. Some of these terms are also in use in Canadian football; for a list of terms unique to that code, see Glossary of Canadian football.

American football, also known as gridiron football, is a team sport played by two teams of eleven players on a rectangular field with goalposts at each end. The offense, the team with possession of the oval-shaped football, attempts to advance down the field by running with the ball or passing it, while the defense, the team without possession of the ball, aims to stop the offense's advance and to take control of the ball for themselves. The offense must advance at least ten yards in four downs or plays; if they fail, they turn over the football to the defense, but if they succeed, they are given a new set of four downs to continue the drive. Points are scored primarily by advancing the ball into the opposing team's end zone for a touchdown or kicking the ball through the opponent's goalposts for a field goal. The team with the most points at the end of a game wins.

In gridiron football, a penalty is a sanction assessed against a team for a violation of the rules, called a foul. Officials initially signal penalties by tossing a bright yellow colored penalty flag onto the field toward or at the spot of a foul.

In gridiron football, a two-point conversion or two-point convert is a play a team attempts instead of kicking a one-point conversion immediately after it scores a touchdown. In a two-point conversion attempt, the team that just scored must run a play from scrimmage close to the opponent's goal line and advance the ball across the goal line in the same manner as if they were scoring a touchdown. If the team succeeds, it earns two additional points on top of the six points for the touchdown, for a total of eight points. If the team fails, no additional points are scored.

In gridiron football, a punt is a kick performed by dropping the ball from the hands and then kicking the ball before it hits the ground. The most common use of this tactic is to punt the ball downfield to the opposing team, usually on the final down, with the hope of giving the receiving team a field position that is more advantageous to the kicking team when possession changes. The result of a typical punt, barring any penalties or extraordinary circumstances, is a first down for the receiving team. A punt is not to be confused with a drop kick, a kick after the ball hits the ground, now rare in both American and Canadian football.

The conversion, try, also known as a point(s) after touchdown, PAT, extra point, two-point conversion, or convert is a gridiron football play that occurs immediately after a touchdown. The scoring team attempts to score one extra point by kicking the ball through the uprights in the manner of a field goal, or two points by passing or running the ball into the end zone in the manner of a touchdown.