Tiziano Vecelli or Vecellio, known in English as Titian, was an Italian (Venetian) Renaissance painter of Lombard origin, considered the most important member of the 16th-century Venetian school. He was born in Pieve di Cadore, near Belluno. During his lifetime he was often called da Cadore, 'from Cadore', taken from his native region.

Salome, also known as Salome III, was a Jewish princess, the daughter of Herod II, who was the son of Herod the Great, with princess Herodias. She was granddaughter of Herod the Great, and stepdaughter of Herod Antipas. She is known from the New Testament, where she is not named, and from an account by Flavius Josephus. In the New Testament, the stepdaughter of Herod Antipas demands and receives the head of John the Baptist. According to Josephus, she was first married to her uncle Philip the Tetrarch, after whose death she married her cousin Aristobulus of Chalcis, thus becoming queen of Armenia Minor.

The Doria Pamphilj Gallery is a large private art collection housed in the Palazzo Doria Pamphilj in Rome, Italy, between Via del Corso and Via della Gatta. The principal entrance is on the Via del Corso. The palace façade on Via del Corso is adjacent to a church, Santa Maria in Via Lata. Like the palace, it is still privately owned by the princely Roman family Doria Pamphili. Tours of the state rooms often culminate in concerts of Baroque and Renaissance music, paying tribute to the setting and the masterpieces it contains.

The Sleeping Venus, also known as the Dresden Venus, is a painting traditionally attributed to the Italian Renaissance painter Giorgione, although it has long been usually thought that Titian completed it after Giorgione's death in 1510. The landscape and sky are generally accepted to be mainly by Titian. In the 21st century, much scholarly opinion has shifted further, to see the nude figure of Venus as also painted by Titian, leaving Giorgione's contribution uncertain. It is in the Gemäldegalerie, Dresden. After World War II, the painting was briefly in possession of the Soviet Union.

Sacred and Profane Love is an oil painting by Titian, probably painted in 1514, early in his career. The painting is presumed to have been commissioned by Niccolò Aurelio, a secretary to the Venetian Council of Ten, whose coat of arms appears on the sarcophagus or fountain, to celebrate his marriage to a young widow, Laura Bagarotto. It perhaps depicts a figure representing the bride dressed in white, sitting beside Cupid and accompanied by the goddess Venus.

The account of the beheading of Holofernes by Judith is given in the deuterocanonical Book of Judith, and is the subject of many paintings and sculptures from the Renaissance and Baroque periods. In the story, Judith, a beautiful widow, is able to enter the tent of Holofernes because of his desire for her. Holofernes was an Assyrian general who was about to destroy Judith's home, the city of Bethulia. Overcome with drink, he passes out and is decapitated by Judith; his head is taken away in a basket.

Palma Vecchio, born Jacopo Palma, also known as Jacopo Negretti, was a Venetian painter of the Italian High Renaissance. He is called Palma Vecchio in English and Palma il Vecchio in Italian to distinguish him from Palma il Giovane, his great-nephew, who was also a painter.

The Venetian painter Titian and his workshop made at least six versions of the same composition showing Danaë, painted between about 1544 and the 1560s. The scene is based on the mythological princess Danaë, as – very briefly – recounted by the Roman poet Ovid, and at greater length by Boccaccio. She was isolated in a bronze tower following a prophecy that her firstborn would eventually kill her father. Although aware of the consequences, Danaë was seduced and became pregnant by Zeus, who, inflamed by lust, descended from Mount Olympus to seduce her in the form of a shower of gold.

A composition of Venus and Adonis by the Venetian Renaissance artist Titian has been painted a number of times, by Titian himself, by his studio assistants and by others. In all there are some thirty versions that may date from the 16th century, the nudity of Venus undoubtedly accounting for this popularity. It is unclear which of the surviving versions, if any, is the original or prime version, and a matter of debate how much involvement Titian himself had with surviving versions. There is a precise date for only one version, that in the Prado in Madrid, which is documented in correspondence between Titian and Philip II of Spain in 1554. However, this appears to be a later repetition of a composition first painted a considerable time earlier, possibly as early as the 1520s.

The Flaying of Marsyas is a painting by the Italian late Renaissance artist Titian, probably painted between about 1570 and his death in 1576, when in his eighties. It is now in the Archbishop's Palace in Kroměříž, Czech Republic and belongs to the Archbishopric of Olomouc. It is one of Titian's last works, and may be unfinished, although there is a partial signature on the stone in the foreground.

The Three Ages of Man is a painting by Titian, dated between 1512 and 1514, and now displayed at the Scottish National Gallery in Edinburgh. The 90 cm high by 151 cm wide Renaissance art work was most likely influenced by Giorgione's themes and motifs of landscapes and nude figures—Titian was known to have completed some of Giorgione's unfinished works after Giorgione died at age 33 of the plague in 1510. The painting represents the artist's conception of the life cycle. Childhood and manhood are synonymous with earthly love and death. These and the approaching old age are drawn realistically. Titian's widely chosen topic in art history, ages of man, mixed with his own allegorical interpretation make The Three Ages of Man one of Titian's most famous works.

Lucretia and her Husband Lucius Tarquinius Collatinus or Tarquin and Lucretia is an oil painting attributed to Titian, dated to around 1515 and now in the Kunsthistorisches Museum in Vienna. The attribution to this artist is traditional but uncertain - the brightened palette suggests it could instead be by Palma Vecchio. However, others identify the painting as part of Titian's series of half-length female figures from 1514 to 1515, which also includes the Flora at the Uffizi, the Woman with a Mirror at the Louvre, the Violante and the Young woman in a black dress in Vienna, Vanity in Munich and the Salome at the Galleria Doria Pamphilj. There is an early copy in the Royal Collection.

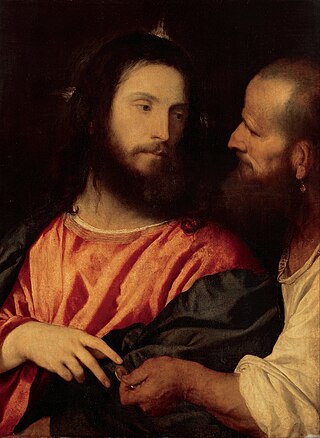

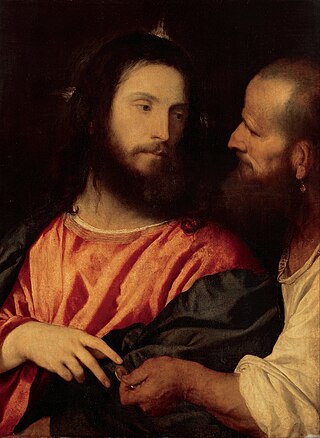

The Tribute Money is a panel painting in oils of 1516 by the Italian late Renaissance artist Titian, now in the Gemäldegalerie Alte Meister in Dresden, Germany. It depicts Christ and a Pharisee at the moment in the Gospels when Christ is shown a coin and says "Render unto Caesar the things that are Caesar's, and unto God the things that are God's". It is signed "Ticianus F.[ecit]", painted on the trim of the left side of the Pharisee's collar.

The Gypsy Madonna is a panel painting of the Madonna and Child in oils of about 1510–11, by Titian, now in the Kunsthistorisches Museum in Vienna. It is a painting made for display in a home rather than a church.

Venus and Musician refers to a series of paintings by the Venetian Renaissance painter Titian and his workshop.

The Bravo is an oil painting usually attributed to Titian, dated to around 1516-17 and now in the Kunsthistorisches Museum in Vienna. The painting can be seen as one of a number of Venetian paintings of the 1510s showing two or three half-length figures with heads close together, often with their expressions and interactions enigmatic. Most of these are "Giorgionesque" genre or tronie subjects where the subjects are anonymous, though the group includes Titian's The Tribute Money, with Christ as the main figure, which in terms of style is similar to this painting, and his Lucretia and her Husband, also in Vienna, where at least the woman's identity is clear, if not that of the man.

The Pardo Venus is a painting by the Venetian artist Titian, completed in 1551 and now in the Louvre Museum. It is also known as Jupiter and Antiope, since it seems to show the story of Jupiter and Antiope from Book VI of the Metamorphoses. It is Titian's largest mythological painting, and was the first major mythological painting produced by the artist for Philip II of Spain. It was long kept in the Royal Palace of El Pardo near Madrid, hence its usual name; whether Venus is actually represented is uncertain. It later belonged to the English and French royal collections.

Venus and Cupid is a 1510–1515 oil on canvas painting by Titian, now in the Wallace Collection in London. It is dated by the model for Venus, who also appeared in other 1510s works by the artist such as his Salome.

Salome, also known as Salome with the Head of John the Baptist, is an oil painting by the Venetian painter Titian, made in about 1550, and currently in the collection of the Museo del Prado in Madrid. It is not to be confused with other compositions of Salome and Judith by Titian.

Salome, also called Salome with the Head of John the Baptist, is an oil painting by Titian, made in around 1570, and currently in a private collection. It is not to be confused with other compositions of Salome and Judith by Titian.