Year 298 BC was a year of the pre-Julian Roman calendar. At the time it was known as the Year of the Consulship of Barbatus and Centumalus. The denomination 298 BC for this year has been used since the early medieval period, when the Anno Domini calendar era became the prevalent method in Europe for naming years.

Marcus Porcius Cato, also known as Cato the Censor, the Elder and the Wise, was a Roman soldier, senator, and historian known for his conservatism and opposition to Hellenization. He was the first to write history in Latin with his Origines, a now fragmentary work on the history of Rome. His work De agri cultura, a rambling work on agriculture, farming, rituals, and recipes, is the oldest extant prose written in the Latin language. His epithet "Elder" distinguishes him from his great-grandson Cato the Younger, who opposed Julius Caesar.

The First, Second, and Third Samnite Wars were fought between the Roman Republic and the Samnites, who lived on a stretch of the Apennine Mountains south of Rome and north of the Lucanian tribe.

The Vatican Museums are the public museums of Vatican City, enclave of Rome. They display works from the immense collection amassed by the Catholic Church and the papacy throughout the centuries, including several of the most well-known Roman sculptures and most important masterpieces of Renaissance art in the world. The museums contain roughly 70,000 works, of which 20,000 are on display, and currently employs 640 people who work in 40 different administrative, scholarly, and restoration departments.

Saturnian meter or verse is an old Latin and Italic poetic form, of which the principles of versification have become obscure. Only 132 complete uncontroversial verses survive. 95 literary verses and partial fragments have been preserved as quotations in later grammatical writings, as well as 37 verses in funerary or dedicatory inscriptions. The majority of literary Saturnians come from the Odysseia, a translation/paraphrase of Homer's Odyssey by Livius Andronicus, and the Bellum Poenicum, an epic on the First Punic War by Gnaeus Naevius.

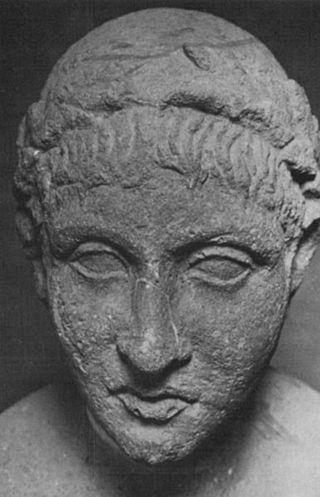

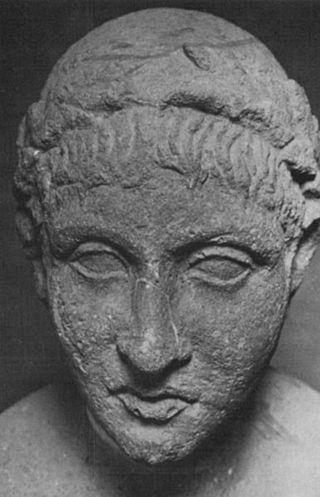

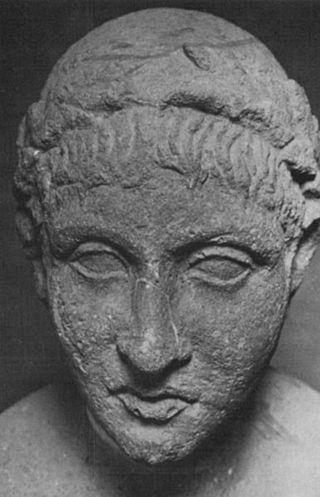

Lucius Cornelius Scipio Barbatus was one of the two elected Roman consuls in 298 BC. He led the Roman army to victory against the Etruscans near Volterra. A member of the noble Roman family of Scipiones, he was the father of Lucius Cornelius Scipio and Gnaeus Cornelius Scipio Asina and great-grandfather of Scipio Africanus.

Aulus Atilius Caiatinus was a Roman general and statesman who achieved prominence for his military activities during the First Punic War against Carthage. As consul in 258 BC, he enjoyed several successes in Sicily, for which he later celebrated a triumph. He undertook further campaigning in Sicily both at sea and on land during a second consulship and then as dictator, becoming the first Roman dictator to lead an army outside mainland Italy.

Res Gestae Divi Augusti is a monumental inscription composed by the first Roman emperor, Augustus, giving a first-person record of his life and accomplishments. The Res Gestae is especially significant because it gives an insight into the image Augustus offered to the Roman people. Various portions of the Res Gestae have been found in modern Turkey. The inscription itself is a monument to the establishment of the Julio-Claudian dynasty that was to follow Augustus.

Saint Peter's tomb is a site under St. Peter's Basilica that includes several graves and a structure said by Vatican authorities to have been built to memorialize the location of Saint Peter's grave. St. Peter's tomb is alleged near the west end of a complex of mausoleums, the Vatican Necropolis, that date between about AD 130 and AD 300. The complex was partially torn down and filled with earth to provide a foundation for the building of the first St. Peter's Basilica during the reign of Constantine I in about AD 330. Though many bones have been found at the site of the 2nd-century shrine, as the result of two campaigns of archaeological excavation, Pope Pius XII stated in December 1950 that none could be confirmed to be Saint Peter's with absolute certainty. Following the discovery of bones that had been transferred from a second tomb under the monument, on June 26, 1968, Pope Paul VI said that the relics of Saint Peter had been identified in a manner considered convincing. Only circumstantial evidence was provided to support the claim.

Tomb WV23, also known as KV23, is located in the Western Valley of the Kings near modern-day Luxor, and was the tomb of Pharaoh Ay of the Eighteenth Dynasty. The tomb was discovered by Giovanni Battista Belzoni in the winter of 1816. Its architecture is similar to that of the tomb of Akhenaten, with a straight descending corridor leading to a "well chamber" that has no shaft. This leads to the burial chamber, which now contains the reconstructed sarcophagus, which had been smashed in antiquity. The tomb had also been anciently desecrated, with many instances of Ay's image or name erased from the wall paintings. Its decoration is similar in content and colour to that of the tomb of Tutankhamun (KV62), with a few differences. On the eastern wall there is a depiction of a fishing and fowling scene, which is not shown in other royal tombs, normally appearing in burials of nobility.

The gens Cornelia was one of the greatest patrician houses at ancient Rome. For more than seven hundred years, from the early decades of the Republic to the third century AD, the Cornelii produced more eminent statesmen and generals than any other gens. At least seventy-five consuls under the Republic were members of this family, beginning with Servius Cornelius Maluginensis in 485 BC. Together with the Aemilii, Claudii, Fabii, Manlii, and Valerii, the Cornelii were almost certainly numbered among the gentes maiores, the most important and powerful families of Rome, who for centuries dominated the Republican magistracies. All of the major branches of the Cornelian gens were patrician, but there were also plebeian Cornelii, at least some of whom were descended from freedmen.

The study of Roman sculpture is complicated by its relation to Greek sculpture. Many examples of even the most famous Greek sculptures, such as the Apollo Belvedere and Barberini Faun, are known only from Roman Imperial or Hellenistic "copies". At one time, this imitation was taken by art historians as indicating a narrowness of the Roman artistic imagination, but, in the late 20th century, Roman art began to be reevaluated on its own terms: some impressions of the nature of Greek sculpture may in fact be based on Roman artistry.

Taurasi is a town and municipality in the province of Avellino, Campania, southern Italy. In antiquity it was a town in Samnium. The town's name probably derives from the Latin Taurus. Over time it changed from Taurasos to Taurasia before changing to its current form. Taurasi is best known for its increasingly famous red wine also named Taurasi, made of Aglianico grapes along with Piedirosso and Barbera grapes.

Publius Cornelius Scipio Nasica Corculum was a politician of the Roman Republic. Born into the illustrious family of the Cornelii Scipiones, he was one of the most important Roman statesmen of the second century BC, being consul two times in 162 and 155 BC, censor in 159 BC, pontifex maximus in 150 BC, and finally princeps senatus in 147 BC.

Lucius Cornelius Scipio, consul in 259 BC during the First Punic War, was a consul and censor of ancient Rome. He was the son of Lucius Cornelius Scipio Barbatus, himself consul and censor, and brother to Gnaeus Cornelius Scipio Asina, who was consul twice. Two of his sons and three of his grandsons also became consuls and were all famous generals. Among these five men, the most famous was Scipio Africanus.

Sempronia was a Roman noblewoman living in the Middle and Late Roman Republic, who was most famous as the sister of the ill-fated Tiberius Gracchus and Gaius Gracchus, and the wife of a Roman general Scipio Aemilianus.

The Tomb of the Scipios, also called the hypogaeum Scipionum, was the common tomb of the patrician Scipio family during the Roman Republic for interments between the early 3rd century BC and the early 1st century AD. Then it was abandoned and within a few hundred years its location was lost.

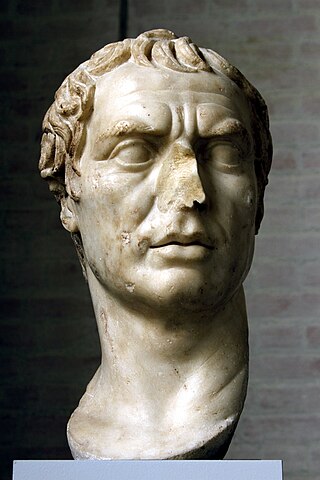

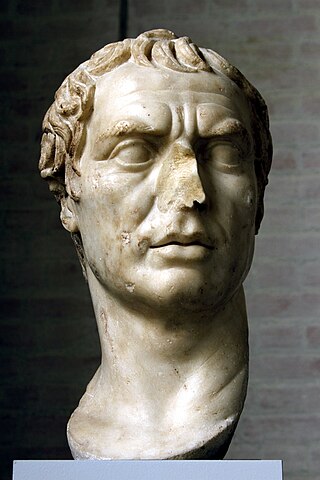

Publius Cornelius Scipio Africanus was a Roman general and statesman, most notable as one of the main architects of Rome's victory against Carthage in the Second Punic War. Often regarded as one of the greatest military commanders and strategists of all time, his greatest military achievement was the defeat of Hannibal at the Battle of Zama in 202 BC. This victory in Africa earned him the honorific epithet Africanus, literally meaning "the African", but meant to be understood as a conqueror of Africa.

Publius Cornelius Scipio was a priest of the Roman Republic, who belonged to the prominent family of the Cornelii Scipiones. He was the grandson of Scipio Africanus and son of P. Cornelius Scipio. He is only known from an inscription found in the Tomb of the Scipios, which tells that he was flamen Dialis, the prestigious priest of Jupiter.

An elogium was an inscription in honour of a deceased person, which was placed on tombs, ancestral images and statues during the Roman age. The elogia are sometimes synonyms with the tituli, the identifying inscriptions on wax images of deceased ancestors that were displayed in the atrium of the domus of noble families, but they are shorter than the laudatio funebris, the funeral oration. Originally, the text was usually written in saturnians, but later it could be in hexameters, iambic hexameters, distichs or in prose. Characteristic of the elogium is the nominative case used for the name of the deceased and not, as it was the case later in the funerary literature, the dative.