Athanasius Kircher was a German Jesuit scholar and polymath who published around 40 major works of comparative religion, geology, and medicine. Kircher has been compared to fellow Jesuit Roger Joseph Boscovich and to Leonardo da Vinci for his vast range of interests, and has been honoured with the title "Master of a Hundred Arts". He taught for more than 40 years at the Roman College, where he set up a wunderkammer. A resurgence of interest in Kircher has occurred within the scholarly community in recent decades.

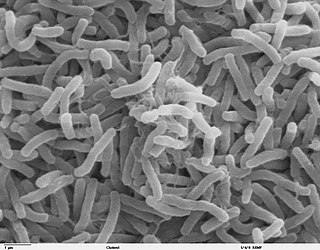

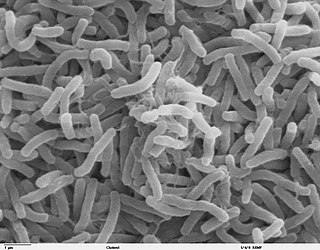

The germ theory of disease is the currently accepted scientific theory for many diseases. It states that microorganisms known as pathogens or "germs" can cause disease. These small organisms, too small to be seen without magnification, invade humans, other animals, and other living hosts. Their growth and reproduction within their hosts can cause disease. "Germ" refers to not just a bacterium but to any type of microorganism, such as protists or fungi, or even non-living pathogens that can cause disease, such as viruses, prions, or viroids. Diseases caused by pathogens are called infectious diseases. Even when a pathogen is the principal cause of a disease, environmental and hereditary factors often influence the severity of the disease, and whether a potential host individual becomes infected when exposed to the pathogen. Pathogens are disease-carrying agents that can pass from one individual to another, both in humans and animals. Infectious diseases are caused by biological agents such as pathogenic microorganisms as well as parasites.

Gaspar Schott was a German Jesuit and scientist, specializing in the fields of physics, mathematics and natural philosophy, and known for his industry.

Filippo Bonanni; S.J. or Buonanni was an Italian Jesuit scholar. His many works included treatises on fields ranging from anatomy to music. He created the earliest practical illustrated guide for shell collectors in 1681, for which he is considered a founder of conchology. He also published a study of lacquer that has been of lasting value since his death.

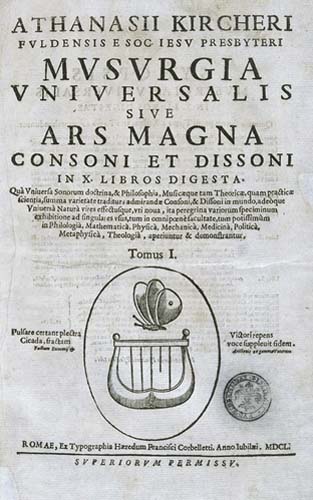

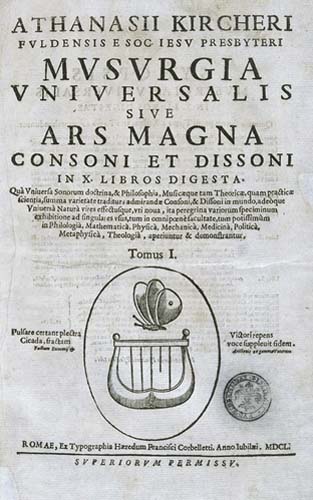

Musurgia Universalis, sive Ars Magna Consoni et Dissoni is a 1650 work by the Jesuit scholar Athanasius Kircher. It was printed in Rome by Ludovico Grignani and dedicated to Archduke Leopold Wilhelm of Austria. It was a compendium of ancient and contemporary thinking about music, its production and its effects. It explored, in particular, the relationship between the mathematical properties of music with health and rhetoric. The work complements two of Kircher's other books: Magnes sive de Arte Magnetica had set out the secret underlying coherence of the universe and Ars Magna Lucis et Umbrae had explored the ways of knowledge and enlightenment. What Musurgia Universalis contained, through its exploration of dissonance within harmony, was an explanation of the presence of evil in the world.

Microbiology is the scientific study of microorganisms, those being of unicellular (single-celled), multicellular, or acellular. Microbiology encompasses numerous sub-disciplines including virology, bacteriology, protistology, mycology, immunology, and parasitology.

Steven Blankaart was a Dutch physician, iatrochemist, and entomologist, who worked on the same field as Jan Swammerdam. Blankaart proved the existence of a capillary system, as had been suggested by Leonardo da Vinci, by spouting up blood vessels, though he failed to realize the true significance of his findings. He is known for his development of injection techniques for this study and for writing the first Dutch book on child medicine. Blankaart translated works of John Mayow.

China Illustrata is the 1667 published book written by the Jesuit Athanasius Kircher (1602–1680) that compiles the 17th-century European knowledge on the Chinese Empire and its neighboring countries. The original Latin title is Athanasii Kircheri e Soc. Jesu China monumentis, qua sacris qua profanis, nec non variis Naturae et artis spectaculis, aliarumque rerum memorabilium argumentis illustrata, auspiciis Leopoldi primi, Roman. Imper. Semper augusti Munificentissimi Mecaenatis.

Phonurgia Nova is a 1673 work by the Jesuit scholar Athanasius Kircher. It is notable for being the first book ever dedicated entirely to the science of acoustics, and for containing the earliest description of an aeolian harp. It was dedicated to the Holy Roman Emperor Leopold I and printed in Kempten by Rudoph Dreherr.

Ars Magnesia was a book on magnetism by the Jesuit scholar Athanasius Kircher in 1631. It was his first published work, written while he was professor of ethics and mathematics, Hebrew and Syriac at the University of Würzburg. It was published in Würzburg by Elias Michael Zink.

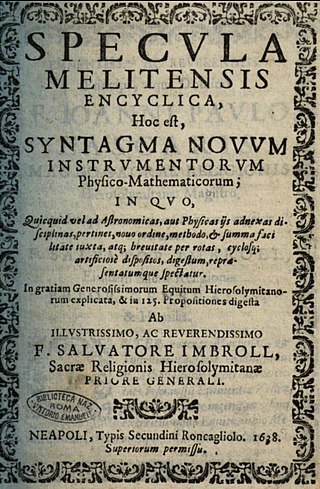

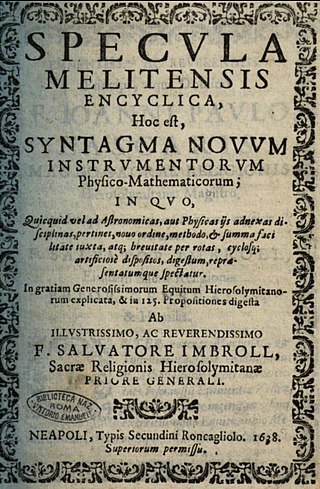

Specula Melitensis Encyclica is a 1638 book by Fra Salvatore Imbroll, describing a machine invented by a Jesuit scholar Athanasius Kircher. It was printed in Naples by Secundino Roncagliolo and dedicated to Giovanni Paolo Lascaris, Grand Master of the Knights of Malta.

Prodromus Coptus sive Aegyptiacus was a 1636 work by the Jesuit scholar Athanasius Kircher. It was published in Rome by the Sacred Congregation for the Propagation of the Faith and dedicated to the Prefect of the Congregation, Cardinal Francesco Barberini. The book was Kircher's first venture into the field of Egyptology, and it also contained the first ever published grammar of the Coptic language.

Itinerarium exstaticum quo mundi opificium is a 1656 work by the Jesuit scholar Athanasius Kircher. It is an imaginary dialogue in which an angel named Cosmiel takes the narrator, Theodidactus, on a journey through the planets. It is the only work by Kircher devoted entirely to astronomy, and one of only two pieces of imaginative fiction by him. A revised and expanded second edition, entitled Iter Exstaticum, was published in 1660.

Polygraphia nova et universalis ex combinatoria arte directa is a 1663 work by the Jesuit scholar Athanasius Kircher. It was one of Kircher's most highly regarded works and his only complete work on the subject of cryptography, although he made passing references to the topic elsewhere. The book was distributed as a private gift to selected European rulers, some of who also received an arca steganographica, a presentation chest containing wooden tallies used to encrypt and decrypt codes.

Lingua Aegyptiaca Restituta was a 1643 work about the Coptic language by the Jesuit scholar Athanasius Kircher. It followed his 1636 volume Prodromus Coptus sive Aegyptiacus, the first ever published grammar of Coptic. Lingua Aegyptiaca Restituta was dedicated to the Holy Roman Emperor Ferdinand III and published in Rome by Herman Scheuss.

Obeliscus Pamphilius is a 1650 work by the Jesuit scholar Athanasius Kircher. It was published in Rome by Ludovico Grignani and dedicated to Pope Innocent X in his jubilee year. The subject of the work was Kircher's attempt to translate the hieroglyphs on the sides of an obelisk erected in the Piazza Navona.

Pantometrum Kircherianum is a 1660 work by the Jesuit scholars Gaspar Schott and Athanasius Kircher. It was dedicated to Christian Louis I, Duke of Mecklenburg and printed in Würzburg by Johann Gottfried Schönwetter. It was a description, with building instructions, of a measuring device called the pantometer, that Kircher had developed some years before. The first edition include 32 copperplate illustrations.

Latium is a 1669 work by the Jesuit scholar Athanasius Kircher. It was dedicated to Pope Clement X and a 1671 edition was published in Amsterdam by Johannes van Waesbergen. The work was the first to discuss the topography, archeology and history of the Lazio region. It was based partly on Kircher's extensive walks in the countryside around Rome, although it included sites that he had probably not visited in person. The work included many illustrations of the contemporary countryside, as well as reconstructions of ancient buildings. It also included an account of his discovery of the ruined sanctuary at Mentorella, which he had already recounted in his 1665 work Historia Eustachio Mariana.

Arithmologia, sive De Abditis Numerorum Mysteriis is a 1665 work by the Jesuit scholar Athanasius Kircher. It was published by Varese, the main printing house for the Jesuit order in Rome in the mid-17th century. It was dedicated to Franz III. Nádasdy, a convert to Catholicism to whom Kircher had previously co-dedicated Oedipus Aegyptiacus. Arithmologia is the only one of Kircher's works devoted entirely to different aspects of number symbolism.

Diatribe de progidiosis crucibus is a 1661 work by the Jesuit scholar Athanasius Kircher. It was printed in Rome by Blasius Deversin and dedicated to Archduke Leopold Wilhelm of Austria. A second edition of the work was published in Rome in 1666 and a German translation appeared in Gaspar Schott's Joco-seriorum naturae et artis.