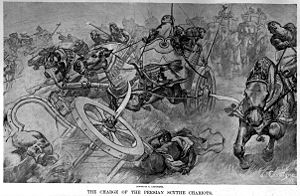

The scythed chariot was a war chariot with scythe blades mounted on each side. It was employed in ancient times.

The scythed chariot was a war chariot with scythe blades mounted on each side. It was employed in ancient times.

The scythed chariot was a modified war chariot. The blades extended horizontally for about 1 m (3 ft 3 in) to each side of the wheels. King Ajatashatru of Magadha was known for inventing the scythed chariot in ca.475 BCE also known as Rathmusala in Sanskrit, a powerful war chariot that gave him a significant advantage in his military campaigns. Ajatashatru used this innovative weapon to defeat the Licchavi Republic after a 16-year long Magadha-Vajji war. The scythed chariot was a key factor in Ajatashatru's ability to expand the territory of the Magadha kingdom and establish its supremacy over eastern India. It gave him a technological edge over his opponents and allowed him to conquer 36 republics in the region.

The Greek general Xenophon (430−354 BC), an eyewitness at the battle of Cunaxa, tells of them: "These had thin scythes extending at an angle from the axles and also under the driver's seat, turned toward the ground".[ full citation needed ] Serrated bronze blades for chariot wheels have also been excavated from Zhou-era pre-imperial Chinese sites.

Dismissing completely 17th to 19th century ideas of a Canaanite, Assyrian, Indian or Macedonian origin, [1] Historian Alexander K. Nefiodkin challenges Xenophon's attribution of scythed chariots to the first Persian king Cyrus, [1] pointing to their notable absence in the invasion of Greece (480−479 BC) by one of his successors, Xerxes I. [2] Instead, he argues that the Persians introduced scythed chariots sometime later during the Greco-Persian Wars, between 467 BC and 458 BC, as a response to their experience fighting against Greek heavy infantry. [3]

In addition, Nefiodkin has responded to the critic J. Rop, summarising that the ancient historian Ctesias of Assyria is unreliable, and that scythed chariots were developed in order to fight ancient Greek hoplite formations, or more generally, heavy infantry. [4]

This section needs additional citations for verification .(March 2021) |

The scythed chariot was pulled by a team of four horses and manned by a crew of up to three men, one driver and two warriors. Theoretically the scythed chariot would plow through infantry lines, cutting combatants in half or at least opening gaps in the line which could be exploited. It was difficult to get horses to charge into the tight phalanx formation of the Greek hoplites (infantry). The scythed chariot avoided this inherent problem for cavalry by using the scythe to cut into the formation even when the horses avoided the men. A disciplined army could diverge as the chariot approached, and then re-form quickly behind it, allowing the chariot to pass without causing many casualties. War chariots had limited military capabilities. They were strictly an offensive weapon and were best suited against infantry in open flat country where the charioteers had room to maneuver. At a time when cavalry were without stirrups, and probably had neither spurs nor an effective saddle, though they certainly had saddle blankets, scythed chariots added weight to a cavalry attack on infantry. Historical sources come from the infantry side of such engagements i.e. the Greek and Roman side. Here is one recorded encounter where scythed chariots were on the winning side:

The soldiers had got into the habit of collecting their supplies carelessly and without taking precautions. There was one occasion when Pharnabazus, with 2 scythed chariots and about 400 cavalry, came on them when they were scattered all over the plain. When the Greeks saw him bearing down on them, they ran to join up with each other, about 700 altogether; but Pharnabazus did not waste time. Putting the chariots in front, and following behind them himself with the cavalry, he ordered a charge. The chariots dashing into the Greek ranks, broke up their close formation, and the cavalry soon cut down about a hundred men. The rest fled and took refuge with Agesilaus, who happened to be close at hand with the hoplites. [5]

The only other recorded example of their successful use seems to be when units of Mithradates VI of Pontus defeated a Bithynian force on the River Amnias in 89 BC. (Appian)

Despite these shortcomings, scythed chariots were used with some success by the Persians and the kingdoms of the Hellenistic Era. They are last known to have been used at the Battle of Zela in 47 BC. The Romans are reported to have defeated this weapon system, not necessarily at this battle, with caltrops. On other occasions the Romans fixed vertical posts in the ground behind which their infantry were safe (Frontinus Stratagems 2,3,17-18) There is a statement in the Scriptores Historiae Augustae Severus Alexander LV that he captured 1,800 scythed chariots. This is universally regarded as false.

Late in the Imperial period, the Romans might have experimented with an unusual variant of the idea that called for cataphract-style lancers to sit on a pair or a single horse drawing a "chariot" reduced to a bare axle with wheels, where the blades were only lowered into the fighting position at the last moment. This would have facilitated manoeuvring before battle. This at least is a reasonable interpretation of the rather enigmatic De rebus bellicis section 12-14.

In the northern Sahara nomadic tribes called Pharusii and Nigrites used scythed chariots c. 22 AD, as Strabo reports: "They have chariots also, armed with scythes." [6]

Regarding the Roman conquest of Britain, contemporary Roman geographer Pomponius Mela mentions:

They make war not only on horseback but also from 2 horse chariots and cars armed in the Gallic fashion – they call them covinni – on which they use axles equipped with scythes. [7]

There is no accepted archaeological evidence concerning scythed chariots. There are some large heavy scythe blades from late Roman Britain which are too unwieldy for a man to use.

However, a scythed chariot appears in The Cattle-Raid of Cooley (Táin Bó Cúailnge), the central epic of the Ulster cycle of Early Irish literature. [8]

One of Leonardo da Vinci's ideas was a scythed chariot. [9]

Hoplites were citizen-soldiers of Ancient Greek city-states who were primarily armed with spears and shields. Hoplite soldiers used the phalanx formation to be effective in war with fewer soldiers. The formation discouraged the soldiers from acting alone, for this would compromise the formation and minimize its strengths. The hoplites were primarily represented by free citizens – propertied farmers and artisans – who were able to afford a linen or bronze armour suit and weapons. It also appears in the stories of Homer, but it is thought that its use began in earnest around the 7th century BC, when weapons became cheap during the Iron Age and ordinary citizens were able to provide their own weapons. Most hoplites were not professional soldiers and often lacked sufficient military training. Some states maintained a small elite professional unit, known as the epilektoi or logades since they were picked from the regular citizen infantry. These existed at times in Athens, Sparta, Argos, Thebes, and Syracuse, among other places. Hoplite soldiers made up the bulk of ancient Greek armies.

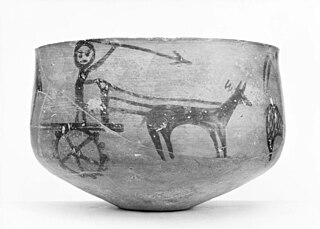

A chariot is a type of cart driven by a charioteer, usually using horses to provide rapid motive power. The oldest known chariots have been found in burials of the Sintashta culture in modern-day Chelyabinsk Oblast, Russia, dated to c. 1950–1880 BCE and are depicted on cylinder seals from Central Anatolia in Kültepe dated to c. 1900 BCE. The critical invention that allowed the construction of light, horse-drawn chariots was the spoked wheel.

A cataphract was a form of armored heavy cavalry that originated in Persia and was fielded in ancient warfare throughout Eurasia and Northern Africa.

The Battle of Gaugamela, also called the Battle of Arbela, took place in 331 BC between the forces of the Army of Macedon under Alexander the Great and the Persian Army under King Darius III. It was the second and final battle between the two kings, and is considered to be the final blow to the Achaemenid Empire, resulting in its complete conquest by Alexander.

The Sacred Band of Thebes was a troop of select soldiers. According to some ancient Greek claims, 150 pairs of male lovers formed the elite force of the Theban army in the 4th century BC, ending Spartan domination. However, historian David D. Leitao did claim that the Sacred Band of Thebes might not have consisted of male lovers. Its predominance began with its crucial role in the Battle of Leuctra in 371 BC. It was annihilated by Philip II of Macedon in the Battle of Chaeronea in 338 BC.

The Battle of Thymbra was the decisive battle in the war between Croesus of the Lydian Kingdom and Cyrus the Great of the Achaemenid Empire. Cyrus, after he had pursued Croesus into Lydia after the drawn Battle of Pteria, met the remains of Croesus' partially-disbanded army in battle on the plain north of Sardis in December 547 BC. Croesus' army was about twice as large and had been reinforced with many new men, but Cyrus still utterly defeated it. That proved to be decisive, and after the 14-day Siege of Sardis, the city and possibly its king fell, and Lydia was conquered by the Persians.

A peltast was a type of light infantry originating in Thrace and Paeonia and named after the kind of shield he carried. Thucydides mentions the Thracian peltasts, while Xenophon in the Anabasis distinguishes the Thracian and Greek peltast troops.

Ancient warfare is war that was conducted from the beginning of recorded history to the end of the ancient period. The difference between prehistoric and ancient warfare is more organization oriented than technology oriented. The development of first city-states, and then empires, allowed warfare to change dramatically. Beginning in Mesopotamia, states produced sufficient agricultural surplus. This allowed full-time ruling elites and military commanders to emerge. While the bulk of military forces were still farmers, the society could portion off each year. Thus, organized armies developed for the first time. These new armies were able to help states grow in size and become increasingly centralized.

Iphicrates was an Athenian general, who flourished in the earlier half of the 4th century BC. He is credited with important infantry reforms that revolutionized ancient Greek warfare by regularizing light-armed peltasts.

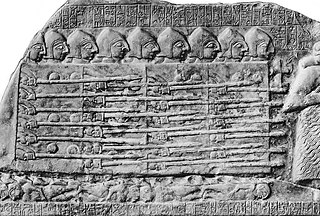

The phalanx was a rectangular mass military formation, usually composed entirely of heavy infantry armed with spears, pikes, sarissas, or similar polearms tightly packed together. The term is particularly used to describe the use of this formation in ancient Greek warfare, although the ancient Greek writers used it to also describe any massed infantry formation, regardless of its equipment. Arrian uses the term in his Array against the Alans when he refers to his legions. In Greek texts, the phalanx may be deployed for battle, on the march, or even camped, thus describing the mass of infantry or cavalry that would deploy in line during battle. They marched forward as one entity.

The Ten Thousand were a force of mercenary units, mainly Greeks, employed by Cyrus the Younger to attempt to wrest the throne of the Persian Empire from his brother, Artaxerxes II. Their march to the Battle of Cunaxa and back to Greece was recorded by Xenophon, one of their leaders, in his work Anabasis.

Cius, later renamed Prusias on the Sea after king Prusias I of Bithynia, was an ancient Greek city bordering the Propontis, in Bithynia and in Mysia, and had a long history, being mentioned by Herodotus, Xenophon, Aristotle, Strabo and Apollonius Rhodius.

The army of the Kingdom of Macedon was among the greatest military forces of the ancient world. It was created and made formidable by King Philip II of Macedon; previously the army of Macedon had been of little account in the politics of the Greek world, and Macedonia had been regarded as a second-rate power.

Warfare occurred throughout the history of Ancient Greece, from the Greek Dark Ages onward. The Greek 'Dark Ages' drew to an end as a significant increase in population allowed urbanized culture to be restored, which led to the rise of the city-states (Poleis). These developments ushered in the period of Archaic Greece. They also restored the capability of organized warfare between these Poleis. The fractious nature of Ancient Greek society seems to have made continuous conflict on this larger scale inevitable.

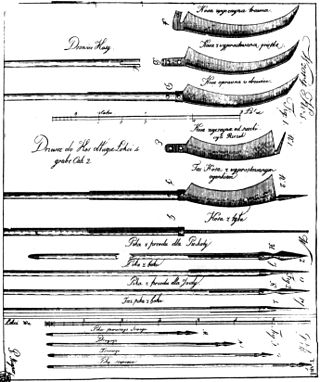

A war scythe or military scythe is a form of pole weapon with a curving single-edged blade with the cutting edge on the concave side of the blade. Its blade bears a superficial resemblance to that of an agricultural scythe from which it is likely to have evolved, but the war scythe is otherwise unrelated to agricultural tools and is a purpose-built infantry melee weapon. The blade of a war scythe has regularly proportioned flats, a thickness comparable to that of a spear or sword blade, and slightly curves along its edge as it tapers to its point. This is different from farming scythes, which have very thin and irregularly curved blades, specialised for mowing grass and wheat only, unsuitable as blades for improvised spears or polearms.

Antandrus or Antandros was an ancient Greek city on the north side of the Gulf of Adramyttium in the Troad region of Anatolia. Its surrounding territory was known in Greek as Ἀντανδρία (Antandria), and included the towns of Aspaneus on the coast and Astyra to the east. It has been located on Devren hill between the modern village of Avcılar and the town of Altınoluk in the Edremit district of Balıkesir Province, Turkey.

Hippeis is a Greek term for cavalry. In ancient Athenian society, after the political reforms of Solon, the hippeus was the second highest of the four social classes. It was composed of men who had at least 300 medimnoi or their equivalent as yearly income. According to the Timocratic Constitution the average citizen had a yearly income of less than 200 medimnoi. This gave the men who made 300 medimnoi the ability to purchase and maintain a war horse during their service to the state.

The Hellenistic armies is a term which refers to the various armies of the successor kingdoms to the Hellenistic period, emerging soon after the death of Alexander the Great in 323 BCE, when the Macedonian empire was split between his successors, known as the Diadochi.

Dascylium, Dascyleium, or Daskyleion, also known as Dascylus, was a town in Anatolia some 30 kilometres (19 mi) inland from the coast of the Propontis, at modern Ergili, Turkey. Its site was rediscovered in 1952 and has since been excavated.

Rathines - the leader of the Cadusii and general of Pharnabazus III.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires |journal= (help) ![]() Media related to Scythed chariots at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Scythed chariots at Wikimedia Commons