The Boston Herald is an American daily newspaper whose primary market is Boston, Massachusetts, and its surrounding area. It was founded in 1846 and is one of the oldest daily newspapers in the United States. It has been awarded eight Pulitzer Prizes in its history, including four for editorial writing and three for photography before it was converted to tabloid format in 1981. The Herald was named one of the "10 Newspapers That 'Do It Right'" in 2012 by Editor & Publisher.

Hearst Communications, Inc., often referred to simply as Hearst, is an American multinational mass media and business information conglomerate based in Hearst Tower in Midtown Manhattan in New York City.

The Houston Chronicle is the largest daily newspaper in Houston, Texas, United States. As of April 2016, it is the third-largest newspaper by Sunday circulation in the United States, behind only The New York Times and the Los Angeles Times. With its 1995 buy-out of long-time rival the Houston Post, the Chronicle became Houston's newspaper of record.

The Hartford Courant is the largest daily newspaper in the U.S. state of Connecticut, and is advertised as the oldest continuously published newspaper in the United States. A morning newspaper serving most of the state north of New Haven and east of Waterbury, its headquarters on Broad Street in Hartford, Connecticut was a short walk from the state capitol. It reports regional news with a chain of bureaus in smaller cities and a series of local editions. It also operates CTNow, a free local weekly newspaper and website.

The St. Louis Post-Dispatch is a regional newspaper based in St. Louis, Missouri, serving the St. Louis metropolitan area. It is the largest daily newspaper in the metropolitan area by circulation, surpassing the Belleville News-Democrat, Alton Telegraph, and Edwardsville Intelligencer. The publication has received 19 Pulitzer Prizes.

The New York Herald Tribune was a newspaper published between 1924 and 1966. It was created in 1924 when Ogden Mills Reid of the New York Tribune acquired the New York Herald. It was regarded as a "writer's newspaper" and competed with The New York Times in the daily morning market. The paper won twelve Pulitzer Prizes during its lifetime.

Anna Eleanor Roosevelt Halsted was an American writer who worked as a newspaper editor and in public relations. Halsted also wrote two children's books published in the 1930s. She was the eldest child and only daughter of the U.S. President Franklin D. Roosevelt and Eleanor Roosevelt and assisted him as his advisor during World War II.

The Seattle Times is a daily newspaper serving Seattle, Washington, United States and its suburbs. Founded in 1891, it has been owned by the Blethen family since 1896. The Seattle Times has the largest circulation of any newspaper in the state of Washington and the Pacific Northwest region. The Seattle Times had a longstanding rivalry with the Seattle Post-Intelligencer until the latter ceased publication in 2009.

The Daily of the University of Washington, usually referred to in Seattle simply as The Daily, is the student newspaper of the University of Washington in Seattle, Washington, USA. It is staffed entirely by University of Washington students, excluding the publisher, advertising adviser, accounting staff, and delivery staff.

The Cincinnati Enquirer is a morning daily newspaper published by Gannett in Cincinnati, Ohio, United States.

The Denver Post is a daily newspaper and website published in the Denver metropolitan area. As of June 2022, it has an average print circulation of 57,265. In 2016, its website received roughly six million monthly unique visitors generating more than 13 million page views, according to comScore.

David Horsey is an American editorial cartoonist and commentator. His cartoons appeared in the Seattle Post-Intelligencer from 1979 until December 2011 and in the Los Angeles Times since that time. His cartoons are syndicated to newspapers nationwide by Tribune Content Agency. He won the Pulitzer Prize for Editorial Cartooning in 1999 and 2003.

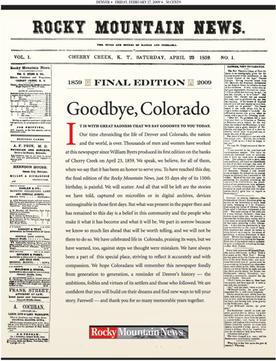

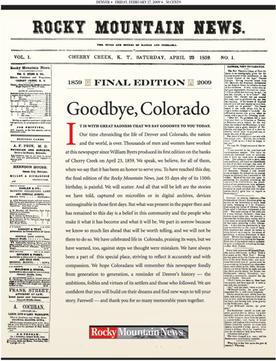

The Rocky Mountain News was a daily newspaper published in Denver, Colorado, from April 23, 1859, until February 27, 2009. It was owned by the E. W. Scripps Company from 1926 until its closing. As of March 2006, the Monday–Friday circulation was 255,427. From the 1940s until 2009, the newspaper was printed in a tabloid format.

The Newspaper Preservation Act of 1970 was an Act of the United States Congress, signed by President Richard Nixon, authorizing the formation of joint operating agreements among competing newspaper operations within the same media market area. It exempted newspapers from certain provisions of antitrust laws. Its drafters argued that this would allow the survival of multiple daily newspapers in a given urban market where circulation was declining. This exemption stemmed from the observation that the alternative is usually for at least one of the newspapers, generally the one published in the evening, to cease operations altogether.

The Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, also known simply as the PG, is the largest newspaper serving metropolitan Pittsburgh in the U.S. state of Pennsylvania. Descended from the Pittsburgh Gazette, established in 1786 as the first newspaper published west of the Allegheny Mountains, the paper formed under its present title in 1927 from the consolidation of the Pittsburgh Gazette Times and The Pittsburgh Post.

The St. Louis Globe-Democrat was a daily print newspaper based in St. Louis, Missouri, from 1852 until 1986. The paper began operations on July 1, 1852, as The Daily Missouri Democrat, changing its name to The Missouri Democrat in 1868, then to The St. Louis Democrat in 1873. It merged with the St. Louis Globe to form the St. Louis Globe-Democrat in 1875.

Anne Melani Bremner is an American attorney and television personality. She has been a television commentator on a number of high-profile cases, including in the murder of Meredith Kercher in Italy as legal counsel and as a spokesperson for the Friends of Amanda Knox.

Clarence John Boettiger was an American journalist and military officer. He was the second husband of Anna Roosevelt, the daughter and first child of President Franklin D. Roosevelt and First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt.

The 1936 Seattle Post-Intelligencer Strike was a labor strike that took place between August 19 and November 29, 1936. It started as the result of two senior staff members being fired after forming an alliance and joining The Newspaper Guild. The strike halted production of the newspaper for the duration of the strike. The strike ended with a formal recognition of The Newspaper Guild.

The Seattle Times Building was an office building in the South Lake Union neighborhood of Seattle, Washington, United States. It served as the former headquarters of The Seattle Times from 1931 to 2011, replacing the earlier Times Square Building. The three-story building was originally built in 1931 and later expanded to accommodate more office space and larger presses.