The Semmelweis reflex or "Semmelweis effect" is a metaphor for the reflex-like tendency to reject new evidence or new knowledge because it contradicts established norms, beliefs, or paradigms. [1]

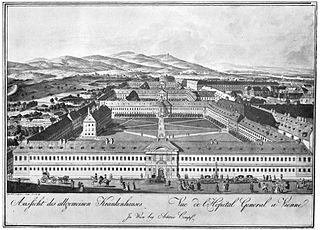

The term derives from the name of Ignaz Semmelweis, a Hungarian physician who discovered in 1847 that childbed fever mortality rates fell ten-fold when doctors disinfected their hands with a chlorine solution before moving from one patient to another, or, most particularly, after an autopsy. (At one of the two maternity wards at the university hospital where Semmelweis worked, physicians performed autopsies on every deceased patient.) Semmelweis's procedure saved many lives by stopping the ongoing contamination of patients (mostly pregnant women) with what he termed "cadaverous particles", twenty years before germ theory was discovered. [2] Despite the overwhelming empirical evidence, his fellow doctors rejected his hand-washing suggestions, often for non-medical reasons. For instance, some doctors refused to believe that a gentleman's hands could transmit disease. [3]

While there is uncertainty regarding its origin and generally accepted use, the expression "Semmelweis Reflex" had been used by the author Robert Anton Wilson. [4] In Wilson's book The Game of Life, Timothy Leary provided the following polemical definition of the Semmelweis reflex: "Mob behavior found among primates and larval hominids on undeveloped planets, in which a discovery of important scientific fact is punished".[ citation needed ]

In the preface to the fiftieth anniversary edition of his book The Myth of Mental Illness , Thomas Szasz says that Semmelweis's biography impressed upon him at a young age, a "deep sense of the invincible social power of false truths." [5]

Confirmation bias is the tendency to favour information that is consistent with prior beliefs or values. [6] When Semmelweis introduced the handwashing proposal, the existing beliefs on disease transmission that other doctors held at that time included miasma theory, which suggests diseases were spread through “bad air”. It was also a common belief that childbed fever happens due to factors like inherent weakness of the patients rather than unclean hands. As the handwashing proposal contradicted the existing beliefs, people may therefore biased against accepting it even though the empirical evidence shows handwashing leads to a significant reduction in maternal rate from 18% to less than 3%. [7]

Authority bias reveals people are more likely to be influenced by the opinions of authority figures. In the days before the medical professions made the connection between germs and disease, senior doctors, including Semmelweis’ professor Johann Klein, were scornful of Semmelweis' idea of preventing bacterial infections through antimicrobial strategies that are now widely accepted. [8] The leading obstetrician, Charles Meigs, was firmly against Semmelweis’s doctrine because “doctors are gentlemen, and gentlemen’s hands are clean.” [9] Throughout human history, obeying authority figures often give better a means of survival because they normally have greater access to resources at the top of the social hierarchy. [10] As a result, although the authority figures can be wrong, the medical community tends to believe them rather than Ignaz Semmelweis, a professor assistant at that time.

The Semmelweis reflex also exemplifies how belief perseverance causes individuals to adhere to their initial beliefs despite contradicting evidence. The human brain has fully developed the cerebral cortex and the prefrontal cortex (PFC), which equips individuals with the power to resist primitive instincts and adaptability but also maintains the status quo and avoids deliberate changes. [11] Therefore, belief perseverance can be interpreted as a coping mechanism that reflects the human tendency to resist change and discomfort. [12]

The Semmelweis proposal was met with unanimous rejection and hostility from the medical community in the 19th century, exemplifying the phenomenon of groupthink, where consensus overrides consideration of alternatives. [13] There may have been pressure to conform to the common beliefs, hindering individuals from accepting Semmelweis's innovative idea. In an open letter, Semmelweis slammed other doctors as “ignorant murderers”, which only served to further isolate him as an outlier from the group. [8] Research on barriers to the transmission of new ideas highlights the challenge of adopting innovative concepts, especially when they are perceived as superior by external entities, as this could pose a threat to the collective pride of the group. [14]

In the book Thinking, Fast and Slow, Daniel Kahneman used the term “theory-induced blindness” to explain how a false theory survived for so long. [15] When people accept a theory, System 1 internalised it as a tool for thinking, making it difficult to realise any potential flaws. Even after discovering that the theory doesn't explain the model well, system 1 automatically assumes that there must be a way to explain it but may not look deeper into what that explanation is. On the other hand, discarding an inherent theory is difficult because it requires the deliberate involvement of system 2.

Semmelweis reflex is often seen as an age-old bias, but it persists in modern times, as illustrated by the delayed recognition of COVID-19's airborne transmission. Despite some evidence indicating aerosol spread, the focus of WHO was primarily on droplet transmission because almost all infectious diseases are spread through droplets. It wasn’t until December 2021 that the WHO officially recognised airborne transmission, which shows the challenge of shifting entrenched beliefs, especially when the prevailing understanding aligns with established norms. Integrating innovative perspectives swiftly in existing frameworks poses a significant challenge. As the epidemiologist Christopher Dye says, “What the WHO says is normally based on a consensus of expert advice and opinion.” [16]

The Semmelweis reflex extends beyond just professionals; the general public also exhibits this tendency. A notable example is evident in the public's response to climate change. Although there is much evidence about climate change and that human activities are the main cause, some individuals still deny or ignore it. In a survey of national attitudes to global warming conducted in Australia (2015), nearly half of the participants (46.5%) expressed scepticism, attributing climate change either to natural processes (38.6%) or outright denying its occurrence (7.9%). [17] These respondents preferred answers consistent with their pre-existing perception that "warming temperatures are simply the result of natural fluctuations", akin to the historical disbelief among doctors that gentlemanly hands were clean and wouldn’t cause disease. However, while the Semmelweis reflex provides a potential explanation for this denial, many other factors contribute to the public's ignorance of climate change.

To mitigate the Semmelweis reflex, one needs to critically evaluate beliefs that are taken for granted, which requires the deliberate engagement of system 2 thinking. Research examining dual-process interventions in diagnostic reasoning shows cognitive forcing tools and guided reflection can enhance diagnostic accuracy. [18] These interventions encourage individuals to actively consider alternative diagnoses that may not be intuitive, thereby enabling them to consciously confront potential biases. However, conflicting findings from other studies suggest that these strategies might not consistently yield the desired results, particularly among students and young doctors. [19] [20]

Most research on the Semmelweis reflex primarily focuses on its historical origins and implications in medical and healthcare settings, particularly in diagnosis. However, the reluctance to embrace new ideas is not limited to medical professionals; it can also hinder progress and innovation within all walks of life. Research on the effects of Semmelweis reflex in different fields is therefore needed to develop more applicable interventions.

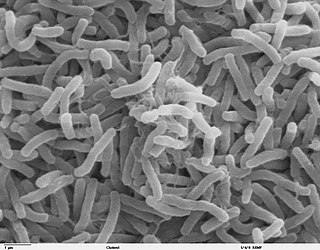

Bacteriology is the branch and specialty of biology that studies the morphology, ecology, genetics and biochemistry of bacteria as well as many other aspects related to them. This subdivision of microbiology involves the identification, classification, and characterization of bacterial species. Because of the similarity of thinking and working with microorganisms other than bacteria, such as protozoa, fungi, and viruses, there has been a tendency for the field of bacteriology to extend as microbiology. The terms were formerly often used interchangeably. However, bacteriology can be classified as a distinct science.

Confirmation bias is the tendency to search for, interpret, favor, and recall information in a way that confirms or supports one's prior beliefs or values. People display this bias when they select information that supports their views, ignoring contrary information, or when they interpret ambiguous evidence as supporting their existing attitudes. The effect is strongest for desired outcomes, for emotionally charged issues, and for deeply entrenched beliefs. Confirmation bias is insuperable for most people, but they can manage it, for example, by education and training in critical thinking skills.

Ignaz Philipp Semmelweis was a Hungarian physician and scientist of German descent, who was an early pioneer of antiseptic procedures, and was described as the "saviour of mothers". Postpartum infection, also known as puerperal fever or childbed fever, consists of any bacterial infection of the reproductive tract following birth, and in the 19th century was common and often fatal. Semmelweis discovered that the incidence of infection could be drastically reduced by requiring healthcare workers in obstetrical clinics to disinfect their hands. In 1847, he proposed hand washing with chlorinated lime solutions at Vienna General Hospital's First Obstetrical Clinic, where doctors' wards had three times the mortality of midwives' wards. The maternal mortality rate dropped from 18% to less than 2%, and he published a book of his findings, Etiology, Concept and Prophylaxis of Childbed Fever, in 1861.

The germ theory of disease is the currently accepted scientific theory for many diseases. It states that microorganisms known as pathogens or "germs" can cause disease. These small organisms, too small to be seen without magnification, invade humans, other animals, and other living hosts. Their growth and reproduction within their hosts can cause disease. "Germ" refers to not just a bacterium but to any type of microorganism, such as protists or fungi, or other pathogens that can cause disease, such as viruses, prions, or viroids. Diseases caused by pathogens are called infectious diseases. Even when a pathogen is the principal cause of a disease, environmental and hereditary factors often influence the severity of the disease, and whether a potential host individual becomes infected when exposed to the pathogen. Pathogens are disease-carrying agents that can pass from one individual to another, both in humans and animals. Infectious diseases are caused by biological agents such as pathogenic microorganisms as well as parasites.

Hand washing, also known as hand hygiene, is the act of cleaning one's hands with soap or handwash and water to remove viruses/bacteria/microorganisms, dirt, grease, or other harmful and unwanted substances stuck to the hands. Drying of the washed hands is part of the process as wet and moist hands are more easily recontaminated. If soap and water are unavailable, hand sanitizer that is at least 60% (v/v) alcohol in water can be used as long as hands are not visibly excessively dirty or greasy. Hand hygiene is central to preventing the spread of infectious diseases in home and everyday life settings.

Postpartum infections, also known as childbed fever and puerperal fever, are any bacterial infections of the female reproductive tract following childbirth or miscarriage. Signs and symptoms usually include a fever greater than 38.0 °C (100.4 °F), chills, lower abdominal pain, and possibly bad-smelling vaginal discharge. It usually occurs after the first 24 hours and within the first ten days following delivery.

Ferdinand Karl Franz Schwarzmann, Ritter von Hebra was an Austrian Empire physician and dermatologist known as the founder of the New Vienna School of Dermatology, an important group of physicians who established the foundations of modern dermatology.

Pyaemia is a type of sepsis that leads to widespread abscesses of a metastatic nature. It is usually caused by the staphylococcus bacteria by pus-forming organisms in the blood. Apart from the distinctive abscesses, pyaemia exhibits the same symptoms as other forms of septicaemia. It was almost universally fatal before the introduction of antibiotics.

The Cry and the Covenant is a novel by Morton Thompson written in 1949 and published by Doubleday. The novel is a fictionalized story of Ignaz Semmelweis, an Austrian-Hungarian physician known for his research into puerperal fever and his advances in medical hygiene. The novel includes historical references, and details into Semmelweis' youth and education, as well as his later studies.

Historically, puerperal fever was a devastating disease. It affected women within the first three days after childbirth and progressed rapidly, causing acute symptoms of severe abdominal pain, fever and debility.

Carl Edvard Marius Levy was professor and head of the Danish Maternity institution in Copenhagen. His name is sometimes spelled "Carl Eduard Marius Levy" or, in foreign literature, "Karl Edouard Marius Levy".

Johann Klein was professor of obstetrics at the University of Salzburg and at the University of Vienna. Johann Baptist Chiari was his son-in-law. In Vienna, he was succeeded by professor Carl Braun in 1856.

Carl Braun, sometimes Carl Rudolf Braun alternative spelling: Karl Braun, or Karl von Braun-Fernwald, name after knighthood Carl Ritter von Fernwald Braun was an Austrian obstetrician. He was born 22 March 1822 in Zistersdorf, Austria, son of the medical doctor Carl August Braun.

Ignaz Semmelweis discovered in 1847 that hand-washing with a solution of chlorinated lime reduced the incidence of fatal childbed fever tenfold in maternity institutions. However, the reaction of his contemporaries was not positive; his subsequent mental disintegration led to him being confined to an insane asylum, where he died in 1865.

János Balassa (1815–1868) was a surgeon, university professor, and one of the leading personalities of the Hungarian medical society at the time. He was also an internationally recognized authority within the field of plastic surgery. Professor of Surgery (1843-) at the University of Pest (Hungary).

Carl Mayrhofer was a physician conducting work on the role of germs in childbed fever.

Etiology, Concept and Prophylaxis of Childbed Fever is a pioneering medical book written by Ignaz Semmelweis and published in 1861, which explains how hygiene in hospitals can drastically reduce unnecessary deaths. The book and concept saved millions of mothers from a preventable streptococcal infection.

Belief perseverance is maintaining a belief despite new information that firmly contradicts it.

Alexander Gordon MA, MD was a Scottish obstetrician best known for clearly demonstrating the contagious nature of puerperal sepsis. By systematically recording details of all visits to women with the condition, he concluded that it was spread from patient to patient by the attending midwife or doctor, and he published these findings in his 1795 paper "Treatise on the Epidemic Puerperal Fever of Aberdeen". On the basis of these conclusions, he advised that the spread could be limited by fumigation of the clothing and burning of the bed linen used by women with the condition and by cleanliness of her medical and midwife attendants. He also recognised a connection between puerperal fever and erysipelas, a skin infection later shown to be caused by the bacterium Streptococcus pyogenes, the same organism that causes puerperal fever. His paper gave insights into the contagious nature of puerperal sepsis around half a century before the better-known publications of Ignaz Semmelweis and Oliver Wendell Holmes and some eighty years before the role of bacteria as infecting agents was clearly understood. Gordon's textbook The Practice of Physik gives valuable insights into medical practice in the later years of the Enlightenment. He advised that clinical decisions be based on personal observations and experience rather than ancient aphorisms.

In the mid to late nineteenth century, scientific patterns emerged which contradicted the widely held miasma theory of disease. These findings led medical science to what we now know as the germ theory of disease. The germ theory of disease proposes that invisible microorganisms are the cause of particular illnesses in both humans and animals. Prior to medicine becoming hard science, there were many philosophical theories about how disease originated and was transmitted. Though there were a few early thinkers that described the possibility of microorganisms, it was not until the mid to late nineteenth century when several noteworthy figures made discoveries which would provide more efficient practices and tools to prevent and treat illness. The mid-19th century figures set the foundation for change, while the late-19th century figures solidified the theory.