Related Research Articles

Leninism is a political ideology developed by Russian Marxist revolutionary Vladimir Lenin that proposes the establishment of the dictatorship of the proletariat led by a revolutionary vanguard party as the political prelude to the establishment of communism. Lenin's ideological contributions to the Marxist ideology relate to his theories on the party, imperialism, the state, and revolution. The function of the Leninist vanguard party is to provide the working classes with the political consciousness and revolutionary leadership necessary to depose capitalism.

Marxism–Leninism is a communist ideology that became the largest faction of the communist movement in the world in the years following the October Revolution. It was the predominant ideology of most socialist governments throughout the 20th century. Developed in Russia by the Bolsheviks, it was the state ideology of the Soviet Union, Soviet satellite states in the Eastern Bloc, and various countries in the Non-Aligned Movement and Third World during the Cold War, as well as the Communist International after Bolshevization.

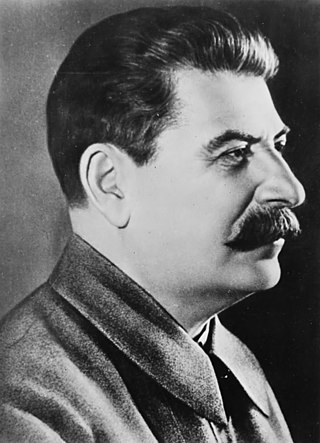

Stalinism is the means of governing and Marxist–Leninist policies implemented in the Soviet Union (USSR) from 1927 to 1953 by Joseph Stalin. It included the creation of a one-party totalitarian police state, rapid industrialization, the theory of socialism in one country, collectivization of agriculture, intensification of class conflict, a cult of personality, and subordination of the interests of foreign communist parties to those of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union, which Stalinism deemed the leading vanguard party of communist revolution at the time. After Stalin's death and the Khrushchev Thaw, a period of de-Stalinization began in the 1950s and 1960s, which caused the influence of Stalin's ideology to begin to wane in the USSR.

Modernity, a topic in the humanities and social sciences, is both a historical period and the ensemble of particular socio-cultural norms, attitudes and practices that arose in the wake of the Renaissance—in the Age of Reason of 17th-century thought and the 18th-century Enlightenment. Some commentators consider the era of modernity to have ended by 1930, with World War II in 1945, or the 1980s or 1990s; the following era is called postmodernity. The term "contemporary history" is also used to refer to the post-1945 timeframe, without assigning it to either the modern or postmodern era.

Postmodernity is the economic or cultural state or condition of society which is said to exist after modernity. Some schools of thought hold that modernity ended in the late 20th century – in the 1980s or early 1990s – and that it was replaced by postmodernity, and still others would extend modernity to cover the developments denoted by postmodernity. The idea of the postmodern condition is sometimes characterized as a culture stripped of its capacity to function in any linear or autonomous state like regressive isolationism, as opposed to the progressive mind state of modernism.

The term "Soviet empire" collectively refers to the world's territories that the Soviet Union dominated politically, economically, and militarily. This phenomenon, particularly in the context of the Cold War, is also called Soviet imperialism by Sovietologists to describe the extent of the Soviet Union's hegemony over the Second World.

The history of the Soviet Union between 1927 and 1953 covers the period in Soviet history from the establishment of Stalinism through victory in the Second World War and down to the death of Joseph Stalin in 1953. Stalin sought to destroy his enemies while transforming Soviet society with central planning, in particular through the forced collectivization of agriculture and rapid development of heavy industry. Stalin consolidated his power within the party and the state and fostered an extensive cult of personality. Soviet secret-police and the mass-mobilization of the Communist Party served as Stalin's major tools in molding Soviet society. Stalin's methods in achieving his goals, which included party purges, ethnic cleansings, political repression of the general population, and forced collectivization, led to millions of deaths: in Gulag labor camps and during famine.

Modernization theory holds that as societies become more economically modernized, wealthier and more educated, their political institutions become increasingly liberal democratic. The "classical" theories of modernization of the 1950s and 1960s, most influentially articulated by Seymour Lipset, drew on sociological analyses of Karl Marx, Emile Durkheim, Max Weber, and Talcott Parsons. Modernization theory was a dominant paradigm in the social sciences in the 1950s and 1960s, and saw a resurgence after 1991, when Francis Fukuyama wrote about the end of the Cold War as confirmation on modernization theory.

High modernism is a form of modernity, characterized by an unfaltering confidence in science and technology as means to reorder the social and natural world. The high modernist movement was particularly prevalent during the Cold War, especially in the late 1950s and 1960s.

Robert Charles Tucker was an American political scientist and historian. Tucker is best remembered as a biographer of Joseph Stalin and as an analyst of the Soviet political system, which he saw as dynamic rather than unchanging.

The view of the Soviet family as the basic social unit in society evolved from revolutionary to conservative; the government of the Soviet Union first attempted to weaken the family and then to strengthen it from the 1930s onwards.

Bednota was a daily newspaper designed and focused toward a peasant readership that was issued by the Central Committee of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union in Moscow, Russia, from March 1918 to January 1931. It has been described as the first Soviet newspaper "designed primarily for the lower-class or common reader".

Communism is a left-wing to far-left sociopolitical, philosophical, and economic ideology within the socialist movement, whose goal is the creation of a communist society, a socioeconomic order centered around common ownership of the means of production, distribution, and exchange that allocates products to everyone in the society based on need. A communist society would entail the absence of private property and social classes, and ultimately money and the state.

Sheila Mary Fitzpatrick is an Australian historian, whose main subjects are history of the Soviet Union and history of modern Russia, especially the Stalin era and the Great Purges, of which she proposes a "history from below", and is part of the "revisionist school" of Communist historiography. She has also critically reviewed the concept of totalitarianism and highlighted the differences between Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union in debates about comparison of Nazism and Stalinism.

The cultural revolution was a set of activities carried out in Soviet Russia and the Soviet Union, aimed at a radical restructuring of the cultural and ideological life of society. The goal was to form a new type of culture as part of the building of a socialist society, including an increase in the proportion of people from proletarian classes in the social composition of the intelligentsia.

This is a select bibliography of post World War II English language books and journal articles about the Revolutionary and Civil War era of Russian (Soviet) history. The sections "General Surveys" and "Biographies" contain books; other sections contain both books and journal articles. Book entries may have references to reviews published in English language academic journals or major newspapers when these could be considered helpful. Additional bibliographies can be found in many of the book-length works listed below; see Further Reading for several book and chapter length bibliographies. The External Links section contains entries for publicly available select bibliographies from universities.

This is a select bibliography of post World War II English language books and journal articles about Stalinism and the Stalinist era of Soviet history. Book entries have references to journal reviews about them when helpful and available. Additional bibliographies can be found in many of the book-length works listed below.

This is a select bibliography of English language books and journal articles about the post-Stalinist era of Soviet history. A brief selection of English translations of primary sources is included. The sections "General Surveys" and "Biographies" contain books; other sections contain both books and journal articles. Book entries have references to journal articles and reviews about them when helpful. Additional bibliographies can be found in many of the book-length works listed below; see Further Reading for several book and chapter-length bibliographies. The External Links section contains entries for publicly available select bibliographies from universities.

David L. Hoffmann is a Distinguished Professor, an American historian, and an expert in Russian, Soviet, and East European history. His other interests include Environment, Health, Technology, and Science, as well as Power, Culture, and the State. Since 2017 he has been Arts and Sciences Distinguished Professor of History at the Ohio State University.

Below is a list of post World War II scholarly books and journal articles written in or translated into English about communism. Items on this list should be considered a non-exhaustive list of reliable sources related to the theory and practice of communism in its different forms.

References

- ↑ McClelland, J. S. 1996. A History of Western Political Thought. Routledge. p. 481

- ↑ Fine, Ben. Social Capital versus Social Theory: Political economy and social science at the turn of the millennium. Routledge, 2001. Pp. 144-145

- ↑ Hoffmann, David L. Stalinist Values: The Cultural Norms of Soviet Modernity, 1917-1941. Cornell University Press. Pp. 7

- ↑ Hoffmann, David L. Stalinist Values: The Cultural Norms of Soviet Modernity, 1917-1941. Cornell University Press. Pp. 7

- ↑ Hoffmann, David L. Stalinist Values: The Cultural Norms of Soviet Modernity, 1917-1941. Cornell University Press. Pp. 7-8

- ↑ Hoffmann, David L. Stalinist Values: The Cultural Norms of Soviet Modernity, 1917-1941. Cornell University Press. Pp. 7