Nichiren Buddhism, also known as Hokkeshū, is a branch of Mahayana Buddhism based on the teachings of the 13th-century Japanese Buddhist priest Nichiren (1222–1282) and is one of the Kamakura period schools. Its teachings derive from some 300–400 extant letters and treatises either authored by or attributed to Nichiren.

Nichiren Shōshū is a branch of Nichiren Buddhism based on the traditionalist teachings of the 13th century Japanese Buddhist priest Nichiren (1222–1282), claiming him as its founder through his senior disciple Nikko Shonin (1246–1333), the founder of Head Temple Taiseki-ji, near Mount Fuji. The lay adherents of the sect are called Hokkeko members. The Enichizan Myohoji Temple in Los Angeles, California serves as the temple headquarters within the United States.

Soka Gakkai is a Japanese Buddhist religious movement based on the teachings of the 13th-century Japanese priest Nichiren. It claims the largest membership among Nichiren Buddhist groups.

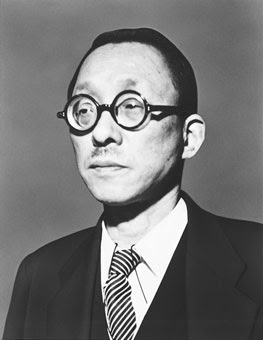

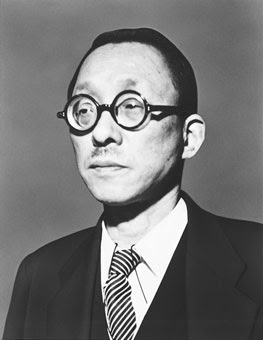

Daisaku Ikeda was a Japanese Buddhist leader, author, philosopher, educator and businessman. He served as the third president and then honorary president of the Soka Gakkai, the largest of Japan's new religious movements. At this time, he became a controversial leader, in Japan and abroad.

The Kōmeitō, also known as the Kōmei Party and Clean Government Party (CGP), was a political party in Japan, initiated by Daisaku Ikeda, and described by various authors as the "political arm" of Soka Gakkai.

Gohonzon (御本尊) is a generic term for a venerated religious object in Japanese Buddhism. It may take the form of a scroll or statuary. The term gohonzon typically refers to the mainstream use of venerated objects within Nichiren Buddhism, referring to the calligraphic paper mandala inscribed by the 13th Japanese Buddhist priest Nichiren to which devotional chanting is directed.

Japanese new religions are new religious movements established in Japan. In Japanese, they are called shinshūkyō (新宗教) or shinkō shūkyō (新興宗教). Japanese scholars classify all religious organizations founded since the middle of the 19th century as "new religions"; thus, the term refers to a great diversity and number of organizations. Most came into being in the mid-to-late twentieth century and are influenced by much older traditional religions including Buddhism and Shinto. Foreign influences include Christianity, the Bible, and the writings of Nostradamus.

Jōsei Toda was a teacher, peace activist and second president of Soka Gakkai from 1951 to 1958. Imprisoned for two years during World War II under violating the Peace Preservation Law and the charge of lèse-majesté from against the war, he emerged from prison intent on rebuilding the Soka Gakkai. He has been described as the architect of the Soka Gakkai, the person chiefly responsible for its existence today.

Tsunesaburō Makiguchi was a Japanese educator who founded and became the first president of the Sōka Kyōiku Gakkai, the predecessor of today's Soka Gakkai.

Nikken Abe was a Japanese Buddhist monk who served as the 67th High Priest of Nichiren Shōshū and chief priest of Taiseki-ji head Temple in Fujinomiya, Japan.

Clark Strand is an American author and lecturer on spirituality and religion. A former Zen Buddhist monk, he was the first Senior Editor of Tricycle: The Buddhist Review. He left that position in 1996 and moved to Woodstock, NY, US to write and teach full-time.

Karel Dobbelaere is a Belgian educator and noted sociologist of religion. Dobbelaere is an Emeritus Professor of both the University of Antwerp and the Katholieke Universiteit Leuven (Louvain) in Belgium. He is past-President and General Secretary of the International Society for the Sociology of Religion.

Minoru Harada is a Japanese Buddhist leader. He is the sixth president of the Soka Gakkai from 9 November 2006. He is also the Supreme Advisor of Sōka University and the Acting President of Soka Gakkai International (SGI).

The Seikyo Shimbun is a Japanese newspaper. It is owned by the Japanese Buddhist religious movement Soka Gakkai. In 1997, it claimed a 5,5 million circulation, but the number is controversial and impossible to verify.

Kōsen-rufu (広宣流布), a phrase found in the Japanese translation of the Buddhist scripture Lotus Sutra, is informally defined to as "world peace through individual happiness." It refers to the future widespread dissemination of the Lotus Sutra.

Bodhisattvas of the Earth, also sometimes referred to as "Bodhisattvas from the Underground," "Bodhisattvas Taught by the Original Buddha," or "earth bodhisattvas," are the infinite number of bodhisattvas who, in the 15th chapter of the Lotus Sutra, emerged from a fissure in the ground. This pivotal story of the Lotus Sutra takes place during the "Ceremony in the Air" which had commenced in the 11th chapter. Later, in the 21st chapter, Shakyamuni passes on to them the responsibility to keep and propagate the Lotus Sutra in the feared future era of the Latter Day of the Law.

The Human Revolution is a roman à clef written by Daisaku Ikeda, the third and honorary president of the Soka Gakkai, chronicling the efforts of Jōsei Toda, the second president of the Soka Gakkai, to construct this Buddhist organization upon his release from Sugamo Prison at the end of World War II. The Human Revolution has sold millions of copies and served as the source of two films of the same name produced by Toho Company and directed by Toshio Masuda. The novel was self-published and printed in 30 volumes.

Zadankai are monthly group discussions held by the members of the buddhist organization Soka Gakkai.

Richard George Causton was a British author, businessman, and the first chairman of the Soka Gakkai International in the UK (SGI-UK).

The Soka School System is a Japanese corporate body that oversees a series of kindergartens, elementary schools, junior high schools, and high schools in Japan and several other countries as well as an educational support and research facility. It is part of a wider network of "Soka" schools which includes Soka University of Japan, Soka University of America, and Soka Women's College. In addition, it has a supportive relationship with several non-affiliated schools and research associations in countries outside of Japan.