A battleship is a large, heavily armored warship with a main battery consisting of large-caliber guns, designed to serve as capital ships with the most intense firepower. Before the rise of supercarriers, battleships were among the largest and most formidable weapon systems ever built.

The Imperial German Navy or the Kaiserliche Marine was the navy of the German Empire, which existed between 1871 and 1919. It grew out of the small Prussian Navy, which was mainly for coast defence. Kaiser Wilhelm II greatly expanded the navy. The key leader was Admiral Alfred von Tirpitz, who greatly expanded the size and quality of the navy, while adopting the sea power theories of American strategist Alfred Thayer Mahan. The result was a naval arms race with Britain, as the German navy grew to become one of the greatest maritime forces in the world, second only to the Royal Navy.

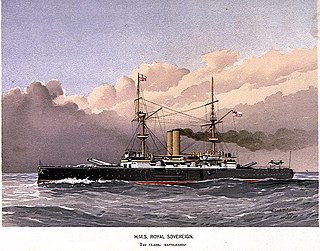

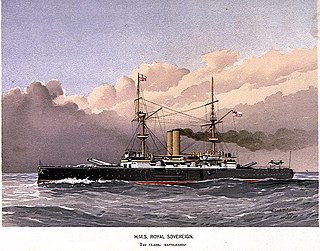

Pre-dreadnought battleships were sea-going battleships built from the mid- to late- 1880s to the early 1900s. Their designs were conceived before the appearance of HMS Dreadnought in 1906 and their classification as "pre-dreadnought" is retrospectively applied. In their day, they were simply known as "battleships" or else more rank-specific terms such as "first-class battleship" and so forth. The pre-dreadnought battleships were the pre-eminent warships of their time and replaced the ironclad battleships of the 1870s and 1880s.

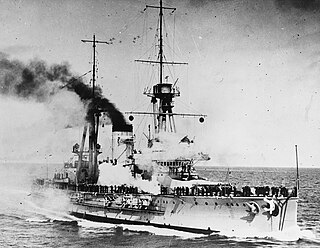

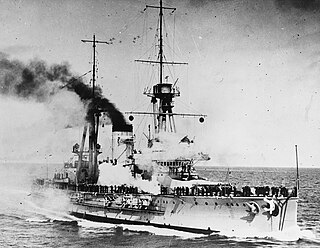

Paris was the third ship of four Courbet-class battleships, the first dreadnoughts built for the French Navy. She was completed before World War I as part of the 1911 naval building programme. She spent the war in the Mediterranean, spending most of 1914 providing gunfire support for the Montenegrin Army until her sister ship Jean Bart was torpedoed by the submarine U-12 on 21 December. She spent the rest of the war providing cover for the Otranto Barrage that blockaded the Austro-Hungarian Navy in the Adriatic Sea.

Although the history of the French Navy goes back to the Middle Ages, its history can be said to effectively begin with Richelieu under Louis XIII.

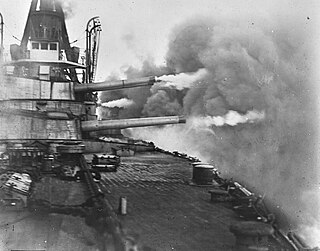

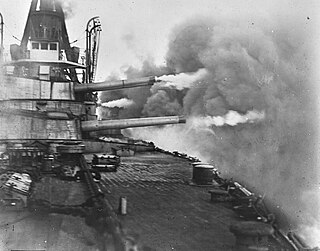

Naval warfare in World War I was mainly characterised by blockade. The Allied Powers, with their larger fleets and surrounding position, largely succeeded in their blockade of Germany and the other Central Powers, whilst the efforts of the Central Powers to break that blockade, or to establish an effective counter blockade with submarines and commerce raiders, were eventually unsuccessful. Major fleet actions were extremely rare and proved less decisive.

España was a Spanish dreadnought battleship, the lead ship of the España class, the two other ships being Alfonso XIII and Jaime I. The ship was built in the early 1910s in the context of a cooperative defensive agreement with Britain and France, as part of a naval construction program to restore the fleet after the losses of the Spanish–American War. She was the only member of the class to be completed before the start of World War I, which significantly delayed completion of the other vessels. The ships were armed with a main battery of eight 305 mm (12 in) guns and were intended to support the French Navy in the event of a major European war.

The España class was a series of three dreadnought battleships that were built for the Spanish Navy between 1909 and 1921: España, Alfonso XIII, and Jaime I. The ships were ordered as part of an informal mutual defense agreement with Britain and France, and were built with British support. The construction of the ships, particularly the third vessel, was significantly delayed by shortages of materiel supplied by the UK during World War I, particularly armaments; Jaime I was almost complete in May 1915 but her guns were not delivered until 1919. The ships were the only dreadnoughts completed by Spain and were the smallest of the type built by any country. The class's limited displacement was necessitated by the constraints imposed by the weak Spanish economy and existing naval infrastructure, requiring compromises on armor and speed to incorporate a main battery of eight 12-inch (305 mm) guns.

Pelayo was a battleship of the Spanish Navy which served in the Spanish fleet from 1888 to 1925. She was the first battleship and the most powerful unit of the Spanish Navy at the time. Despite its modern design for the time, Pelayo and the rest of the Spanish Asia-Pacific Rescue Squadron never engaged in combat during the Spanish–American War. Some historians have argued that had the battleship, along with the modern armored cruiser Carlos V, participated directly in the conflict the course of the war would have been altered dramatically and possibly lead to a Spanish victory, thus retaining Spain's status as a colonial power.

Alfonso XIII was the second of three España-class dreadnought battleships built in the 1910s for the Spanish Navy. Named after King Alfonso XIII of Spain, the ship was not completed until 1915 owing to a shortage of materials that resulted from the start of World War I the previous year. The España class was ordered as part of a naval construction program to rebuild the fleet after the losses of the Spanish–American War; the program began in the context of closer Spanish relations with Britain and France. The ships were armed with a main battery of eight 305 mm (12 in) guns and were intended to support the French Navy in the event of a major European war.

Jaime I was a Spanish dreadnought battleship, the third and final member of the España class, which included two other ships: España and Alfonso XIII. Named after King James I of Aragon, Jaime I was built in the early 1910s, though her completion was delayed until 1921 owing to a shortage of materials that resulted from the start of World War I in 1914. The class was ordered as part of a naval construction program to rebuild the fleet after the losses of the Spanish–American War in the context of closer Spanish relations with Britain and France. The ships were armed with a main battery of eight 305 mm (12 in) guns and were intended to support the French Navy in the event of a major European war.

Minas Geraes, spelled Minas Gerais in some sources, was a dreadnought battleship of the Brazilian Navy. Named in honor of the state of Minas Gerais, the ship was laid down in April 1907 as the lead ship of its class, making the country the third to have a dreadnought under construction and igniting a naval arms race between Brazil, Argentina, and Chile.

ARA Moreno was a dreadnought battleship designed by the American Fore River Shipbuilding Company for the Argentine Navy. Named after Mariano Moreno, a key member of the first independent government of Argentina, the First Assembly, Moreno was the second dreadnought of the Rivadavia class, and the fourth built during the South American dreadnought race.

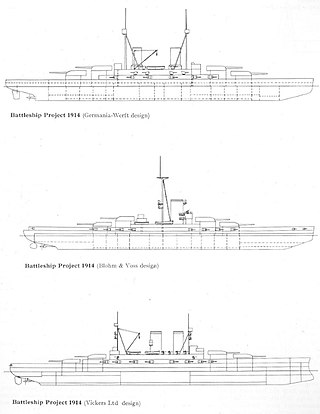

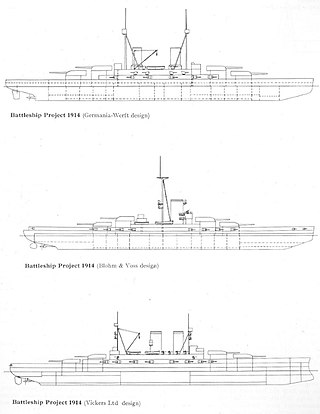

A Dutch proposal to build new battleships was originally tendered in 1912, after years of concern over the expansion of the Imperial Japanese Navy and the withdrawal of allied British warships from the China Station. Only four coastal defense ships were planned, but naval experts and the Tweede Kamer believed that acquiring dreadnoughts would provide a stronger defense for the Nederlands-Indië, so a Royal Commission was formed in June 1912.

A naval arms race among Argentina, Brazil and Chile—the wealthiest and most powerful countries in South America—began in the early twentieth century when the Brazilian government ordered three dreadnoughts, formidable battleships whose capabilities far outstripped older vessels in the world's navies.

The Reina Victoria Eugenia class was a class of three battleships of the Spanish Navy authorized as the Plan de la Segunda Escuadra under the Navy Law of 1913. The class, as well as the lead ship, were named for King Alfonso XIII's English queen consort, Victoria Eugenie of Battenberg. The other two ships were classified as "B" and "C". It was supposed to be designed by Vickers-Armstrongs, and built by John Brown. The ships were never built due to Britain's involvement in World War I, which halted all foreign projects being constructed in British yards.

The Spanish Republican Navy was the naval arm of the Armed Forces of the Second Spanish Republic, the legally established government of Spain between 1931 and 1939.

The Pact of Cartagena was an exchange of notes that took place at Cartagena on 16 May 1907 between France, Great Britain, and Spain. The parties declared their intention to preserve the status quo in the western Mediterranean and in the Atlantic, especially their insular and coastal possessions. The pact aligned Spain with the Anglo-French entente cordiale against Germany's ambitions in Morocco, where both Spain and France had mutually recognised spheres of influence.