Organized crime is a category of transnational, national, or local group of centralized enterprises run to engage in illegal activity, most commonly for profit. While organized crime is generally thought of as a form of illegal business, some criminal organizations, such as terrorist groups, rebel forces, and separatists, are politically motivated. Many criminal organizations rely on fear or terror to achieve their goals or aims as well as to maintain control within the organization and may adopt tactics commonly used by authoritarian regimes to maintain power. Some forms of organized crime simply exist to cater towards demand of illegal goods in a state or to facilitate trade of goods and services that may have been banned by a state. Sometimes, criminal organizations force people to do business with them, such as when a gang extorts protection money from shopkeepers. Street gangs may often be deemed organized crime groups or, under stricter definitions of organized crime, may become disciplined enough to be considered organized. A criminal organization can also be referred to as an outfit, a gang, crime family, mafia, mob, (crime) ring, or syndicate; the network, subculture, and community of criminals involved in organized crime may be referred to as the underworld or gangland. Sociologists sometimes specifically distinguish a "mafia" as a type of organized crime group that specializes in the supply of extra-legal protection and quasi-law enforcement. Academic studies of the original "Mafia", the Italian Mafia generated an economic study of organized crime groups and exerted great influence on studies of the Russian mafia, the Chinese triads, the Hong Kong triads, and the Japanese yakuza.

In sociology, anomie is a social condition defined by an uprooting or breakdown of any moral values, standards or guidance for individuals to follow; which leads to people disrespecting their social values. Anomie is believed to possibly evolve from conflict of belief systems and causes breakdown of social bonds between an individual and the community. An example is alienation in a person that can progress into a dysfunctional inability to integrate within normative situations of their social world such as finding a job, achieving success in relationships, etc.

In criminology, corporate crime refers to crimes committed either by a corporation, or by individuals acting on behalf of a corporation or other business entity. For the worst corporate crimes, corporations may face judicial dissolution, sometimes called the "corporate death penalty", which is a legal procedure in which a corporation is forced to dissolve or cease to exist.

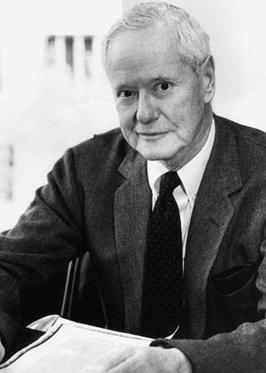

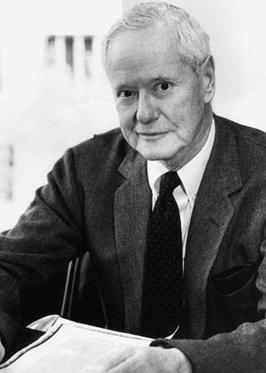

Robert King Merton was an American sociologist who is considered a founding father of modern sociology, and a major contributor to the subfield of criminology. He served as the 47th president of the American Sociological Association. He spent most of his career teaching at Columbia University, where he attained the rank of University Professor. In 1994 he was awarded the National Medal of Science for his contributions to the field and for having founded the sociology of science.

Structural functionalism, or simply functionalism, is "a framework for building theory that sees society as a complex system whose parts work together to promote solidarity and stability".

The Chicago school refers to a school of thought in sociology and criminology originating at the University of Chicago whose work was influential in the early 20th century.

In criminology, blue-collar crime is any crime committed by an individual from a lower social class as opposed to white-collar crime which is associated with crime committed by someone of a higher-level social class. While blue-collar crime has no official legal classification, it holds to a general net group of crimes. These crimes are primarily small scale, for immediate beneficial gain to the individual or group involved in them. This can also include personal related crimes that can be driven by immediate reaction, such as during fights or confrontations. These crimes include but are not limited to: Narcotic production or distribution, sexual assault, theft, burglary, assault or murder.

In criminology, subcultural theory emerged from the work of the Chicago School on gangs and developed through the symbolic interactionism school into a set of theories arguing that certain groups or subcultures in society have values and attitudes that are conducive to crime and violence. The primary focus is on juvenile delinquency because theorists believe that if this pattern of offending can be understood and controlled, it will break the transition from teenage offender into habitual criminal. Some of the theories are functionalist, assuming that criminal activity is motivated by economic needs, while others posit a social class rationale for deviance.

A sociological theory is a supposition that intends to consider, analyze, and/or explain objects of social reality from a sociological perspective, drawing connections between individual concepts in order to organize and substantiate sociological knowledge. Hence, such knowledge is composed of complex theoretical frameworks and methodology.

Marxist criminology is one of the schools of criminology. It parallels the work of the structural functionalism school which focuses on what produces stability and continuity in society but, unlike the functionalists, it adopts a predefined political philosophy. As in conflict criminology, it focuses on why things change, identifying the disruptive forces in industrialized societies, and describing how society is divided by power, wealth, prestige, and the perceptions of the world. "The shape and character of the legal system in complex societies can be understood as deriving from the conflicts inherent in the structure of these societies which are stratified economically and politically". It is concerned with the causal relationships between society and crime, i.e. to establish a critical understanding of how the immediate and structural social environment gives rise to crime and criminogenic conditions.

Right realism, in criminology, also known as New Right Realism, Neo-Classicism, Neo-Positivism, or Neo-Conservatism, is the ideological polar opposite of left realism. It considers the phenomenon of crime from the perspective of political conservatism and asserts that it takes a more realistic view of the causes of crime and deviance, and identifies the best mechanisms for its control. Unlike the other schools of criminology, there is less emphasis on developing theories of causality in relation to crime and deviance. The school employs a rationalist, direct and scientific approach to policy-making for the prevention and control of crime. Some politicians who subscribe to the perspective may address aspects of crime policy in ideological terms by referring to freedom, justice, and responsibility. For example, they may be asserting that individual freedom should only be limited by a duty not to use force against others. This, however, does not reflect the genuine quality in the theoretical and academic work and the real contribution made to the nature of criminal behaviour by criminologists of the school.

Integrative criminology reacts against single theory or methodology approaches, and adopts an interdisciplinary paradigm for the study of criminology and penology. Integration is not new. It informed the groundbreaking work of Merton (1938), Sutherland (1947), and Cohen (1955), but it has become a more positive school over the last twenty years.

In sociology, the social disorganization theory is a theory developed by the Chicago School, related to ecological theories. The theory directly links crime rates to neighbourhood ecological characteristics; a core principle of social disorganization theory that states location matters. In other words, a person's residential location is a substantial factor shaping the likelihood that that person will become involved in illegal activities. The theory suggests that, among determinants of a person's later illegal activity, residential location is as significant as or more significant than the person's individual characteristics. For example, the theory suggests that youths from disadvantaged neighborhoods participate in a subculture which approves of delinquency, and that these youths thus acquire criminality in this social and cultural setting.

Deviance or the sociology of deviance explores the actions and/or behaviors that violate social norms across formally enacted rules as well as informal violations of social norms. Although deviance may have a negative connotation, the violation of social norms is not always a negative action; positive deviation exists in some situations. Although a norm is violated, a behavior can still be classified as positive or acceptable.

Radical criminology states that society "functions" in terms of the general interests of the ruling class rather than "society as a whole" and that while the potential for conflict is always present, it is continually neutralised by the power of a ruling class. Radical criminology is related to critical and conflict criminology in its focus on class struggle and its basis in Marxism. Radical criminologists consider crime to be a tool used by the ruling class. Laws are put into place by the elite and are then used to serve their interests at the peril of the lower classes. These laws regulate opposition to the elite and keep them in power.

Robert Agnew is the Samuel Candler Dobbs Professor of Sociology at Emory University and past president of the American Society of Criminology.

Self-estrangement is the idea conceived by Karl Marx in Marx's theory of alienation and Melvin Seeman in his five logically distinct psychological states that encompasses alienation. As spoken by Marx, self-estrangement is "the alienation of man's essence, man's loss of objectivity and his loss of realness as self-discovery, manifestation of his nature, objectification and realization". Self-estrangement is when a person feels alienated from others and society as a whole. A person may feel alienated by his work by not feeling like he has meaning to his work, therefore losing their sense of self at the work place. Self-estrangement contributes to burnout at work and a lot of psychological stress.

General strain theory (GST) is a theory of criminology developed by Robert Agnew. General strain theory has gained a significant amount of academic attention since being developed in 1992. Robert Agnew's general strain theory is considered to be a solid theory, has accumulated a significant amount of empirical evidence, and has also expanded its primary scope by offering explanations of phenomena outside of criminal behavior. This theory is presented as a micro-level theory because it focuses more on a single person at a time rather than looking at the whole of society.

Criminology is the interdisciplinary study of crime and deviant behaviour. Criminology is a multidisciplinary field in both the behavioural and social sciences, which draws primarily upon the research of sociologists, political scientists, economists, legal sociologists, psychologists, philosophers, psychiatrists, social workers, biologists, social anthropologists, scholars of law and jurisprudence, as well as the processes that define administration of justice and the criminal justice system.

Walter Reckless was an American criminologist known for his containment theory.