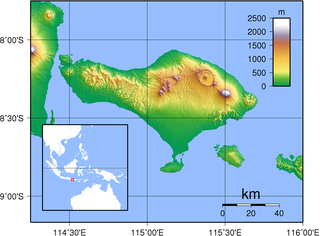

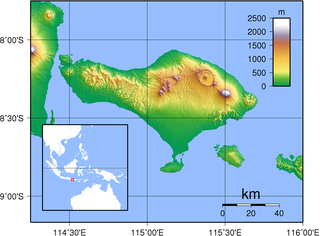

Bali is a province of Indonesia and the westernmost of the Lesser Sunda Islands. East of Java and west of Lombok, the province includes the island of Bali and a few smaller offshore islands, notably Nusa Penida, Nusa Lembongan, and Nusa Ceningan to the southeast. The provincial capital, Denpasar, is the most populous city in the Lesser Sunda Islands and the second-largest, after Makassar, in Eastern Indonesia. The upland town of Ubud in Greater Denpasar is considered Bali's cultural centre. The province is Indonesia's main tourist destination, with a significant rise in tourism since the 1980s, and becoming an Indonesian area of overtourism. Tourism-related business makes up 80% of the Bali economy.

Denpasar is the capital city of the province of Bali, Indonesia. Denpasar is the main gateway to the Bali island, the city is also a hub for other cities in the Lesser Sunda Islands.

The Balinese people are an Austronesian ethnic group native to the Indonesian island of Bali. The Balinese population of 4.2 million live mostly on the island of Bali, making up 89% of the island's population. There are also significant populations on the island of Lombok and in the easternmost regions of Java.

Tabanan is one of the regencies (kabupaten) in Bali, Indonesia. Relatively underdeveloped, Tabanan Regency has an area of 839.33 km2 and had a population of 386,850 in 2000, rising to 420,913 in 2010, then 461,630 at the 2020 census; the official estimate as at mid 2022 was 469,340. Its regency seat is the town of Tabanan. One of the popular tourism attractions located in Tabanan is the offshore rocky islet of Tanah Lot.

Bedugul is a mountain lake resort area in Bali, Indonesia, located in the centre-north region of the island near Lake Bratan on the road between Denpasar and Singaraja. The area covers the villages of Bedugul itself, Candikuning, Pancasari, Pacung and Wanagiri amongst others.

Rice production in Indonesia is an important part of the national economy. Indonesia is the third-largest producer of rice in the world.

The Dutch conquest of South Bali in 1906 was a Dutch military intervention in Bali as part of the Dutch colonial conquest of the Indonesian islands, killing an estimated 1,000 people. It was part of the final takeover of the Netherlands East-Indies and the fifth Dutch military intervention in Bali. The campaign led to the deaths of the Balinese rulers of Badung and Tabanan kingdoms, their wives and children and followers. This conquest weakened the remaining independent kingdoms of Klungkung and Bangli, leading to their invasion two years later.

Pura Ulun Danu Batur is a Hindu Balinese temple located on the island of Bali, Indonesia. As one of the Pura Kahyangan Jagat, Pura Ulun Danu Batur is one of the most important temples in Bali which acted as the maintainer of harmony and stability of the entire island. Pura Ulun Danu Batur represents the direction of the North and is dedicated to the god Vishnu and the local goddess Dewi Danu, goddess of Lake Batur, the largest lake in Bali. Following the destruction of the original temple compound, the temple was relocated and rebuilt in 1926. The temple, along with 3 other sites in Bali, form the Cultural Landscape of Bali Province which was inscribed as a World Heritage Site by UNESCO in 2012.

Dewi Danu is the water goddess of the Balinese Hindus, who call their belief-system Agama Tirta, or belief-system of the water. She is one of two supreme deities in the Balinese tradition.

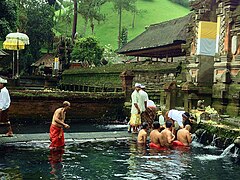

A Pura is a Balinese Hindu temple and the place of worship for adherents of Balinese Hinduism in Indonesia. Puras are built following rules, style, guidance, and rituals found in Balinese architecture. Most puras are found on the island of Bali, where Hinduism is the predominant religion; however many puras exist in other parts of Indonesia where significant numbers of Balinese people reside. Mother Temple of Besakih is the most important, largest, and holiest temple in Bali. Many Puras have been built in Bali, leading it to be titled "the Island of a Thousand Puras".

Anggabaya is a small village in Bali, Indonesia.

Negara: The Theatre State in Nineteenth-Century Bali is a 1980 book written by anthropologist Clifford Geertz. Geertz argues that the pre-colonial Balinese state was not a "hydraulic bureaucracy" nor an oriental despotism, but rather, an organized spectacle. The noble rulers of the island were less interested in administering the lives of the Balinese than in dramatizing their rank and enhance political superiority through large public rituals and ceremonies. These cultural processes did not support the state, he argues, but were the state.

It is perhaps most clear in what was, after all, the master image of political life: kingship. The whole of the negara - court life, the traditions that organized it, the extractions that supported it, the privileges that accompanied it - was essentially directed toward defining what power was; and what power was what kings were. Particular kings came and went, 'poor passing facts' anonymized in titles, immobilized in ritual, and annihilated in bonfires. But what they represented, the model-and-copy conception of order, remained unaltered, at least over the period we know much about. The driving aim of higher politics was to construct a state by constructing a king. The more consummate the king, the more exemplary the centre. The more exemplary the centre, the more actual the realm.

Balinese architecture is a vernacular architecture tradition of Balinese people that inhabits the volcanic island of Bali, Indonesia. Balinese architecture is a centuries-old architectural tradition influenced by Balinese culture developed from Hindu influences through ancient Javanese intermediary, as well as pre-Hindu elements of native Balinese architecture.

The Ubud Palace, officially Puri Saren Agung, is a historical building complex situated in Ubud, Gianyar Regency of Bali, Indonesia.

Pura Taman Ayun is a compound of Balinese temple and garden located in Mengwi district (kecamatan) in Badung Regency, Bali, Indonesia. Its water features are an integral part of the local subak system.

Tegenungan Waterfall is a waterfall in Bali, Indonesia. It is located at the village of Tegenungan Kemenuh, also known as Kemenuh Village on the Petanu River in the Gianyar Regency, north from the capital Denpasar and close to the Balinese artist village of Ubud. The waterfall is isolated but has become a popular tourist attraction. It is one of the few waterfalls in Bali that is not situated in highlands or mountainous territory. The amount and clarity of the water at the site depend on rainfall but it contains green surroundings with fresh water that can be swum in. The waterfall includes varying highs that can be climbed after the descent down stairs to reach it. This attraction also features a viewing point to the jungle and waterfall at the main entrance.

Trunyan or Terunyan is a Balinese village (banjar) located on the eastern shore of Lake Batur, a caldera lake in Bangli Regency, central Bali, Indonesia. The village is one of the most notable homes of the Bali Aga people, the others being the villages of Tenganan and Sambiran. Trunyan is notable for its peculiar treatment of dead bodies, in which they are placed openly on the ground, simply covered with cloth and bamboo canopies, and left to decompose. The influence of a nearby tree is said to remove the putrid smell of the corpses.

Pura Beji Sangsit is a Balinese temple or pura located in Sangsit, Buleleng, on the island of Bali, Indonesia. The village of Sangsit is located around 8 kilometres (5.0 mi) east of Singaraja. Pura Beji is dedicated to the rice goddess Dewi Sri, and is revered especially by the farmers around the area. Pura Beji is an example of a stereotypical northern Balinese architecture with its relatively heavier decorations than it is southern Balinese counterpart, and its typical foliage-like carvings.

Penglipuran is one of the traditional villages or kampung located in Bangli Regency, Bali Province, Indonesia. The village is famous as a tourist destinations in Bali because the villagers still preserve their traditional culture in their daily lives. The architecture of buildings and land processing still follow the concept of Tri Hita Karana, the philosophy of Balinese society regarding the balance of relations between God, humans and their environment. Penglipuran succeeded in building tourism that benefited all of its community without losing its culture and traditions. In 1995, Penglipuran also received a Kalpataru award from the Indonesian government for its efforts to protect the bamboo forest in their local ecosystem.