Pyrmont is an inner-city suburb of Sydney, in the state of New South Wales, Australia 2 kilometres south-west of the Sydney central business district in the local government area of the City of Sydney. It is also part of the Darling Harbour region. As of 2011, it is Australia's most densely populated suburb.

The Pyrmont Bridge, a heritage-listed swing bridge across Cockle Bay, is located in Darling Harbour, part of Port Jackson, west of the central business district in the City of Sydney local government area of New South Wales, Australia. Opened in 1902, the bridge initially carried motor vehicle traffic via the Pyrmont Bridge Road between the central business district and Pyrmont. Since 1981 the bridge has carried pedestrian and bicycle traffic only, as motor vehicles were diverted to adjacent freeway overpasses. The bridge was added to the New South Wales State Heritage Register on 28 June 2002, the centenary of its opening.

The architecture of Sydney, Australia’s oldest city, is not characterised by any one architectural style, but by an extensive juxtaposition of old and new architecture over the city's 200-year history, from its modest beginnings with local materials and lack of international funding to its present-day modernity with an expansive skyline of high rises and skyscrapers, dotted at street level with remnants of a Victorian era of prosperity.

Edmund Thomas Blacket was an Australian architect, best known for his designs for the University of Sydney, St. Andrew's Cathedral, Sydney and St. Saviour's Cathedral, Goulburn.

Australian non-residential architectural styles are a set of Australian architectural styles that apply to buildings used for purposes other than residence and have been around only since the first colonial government buildings of early European settlement of Australia in 1788.

All Souls is an Anglican church in the Diocese of Sydney. The church is located in the corner of Norton and Marion Streets, Leichhardt, New South Wales, Australia.

The St Saviour's Cathedral is the heritage-listed cathedral church of the Anglican Diocese of Canberra and Goulburn in Goulburn, Goulburn Mulwaree Council, New South Wales, Australia. The cathedral is dedicated to Jesus, in his title of Saviour. The current dean is the Very Reverend Phillip Saunders. It was added to the New South Wales State Heritage Register on 20 April 2009.

The General Post Office is a heritage-listed landmark building located in Martin Place, Sydney, New South Wales, Australia. The original building was constructed in two stages beginning in 1866 and was designed under the guidance of Colonial Architect James Barnet. Composed primarily of local Sydney sandstone, mined in Pyrmont, the primary load-bearing northern façade has been described as "the finest example of the Victorian Italian Renaissance Style in NSW" and stretches 114 metres (374 ft) along Martin Place, making it one of the largest sandstone buildings in Sydney.

The Hunter Baillie Memorial Presbyterian Church is a heritage–listed Presbyterian church, located in the inner western Sydney suburb of Annandale, New South Wales, Australia.

Glebe Island was a major port facility in Sydney Harbour and, in association with the adjacent White Bay facility, was the primary receiving venue for imported cars and dry bulk goods in the region until 2008. It is surrounded by White, Johnstons, and Rozelle Bays. Whilst retaining its original title as an "island", it has long been infilled to the shoreline of the suburb of Rozelle and connected by the Glebe Island Bridge to Pyrmont.

The University of Sydney Quadrangle is a prominent quadrangle formed through the construction of several Sydney sandstone buildings located within The University of Sydney Camperdown Campus, adjacent to Parramatta Road, in Sydney, New South Wales, Australia. The Quadrangle is also called The University of Sydney Main Quadrangle. The Quadrangle and its associated main building and interior was listed on the City of Sydney local government heritage list on 14 December 2012.

The Garrison Church is a heritage-listed active Anglican church building located at Argyle Street in the inner city Sydney suburb of Millers Point in the City of Sydney local government area of New South Wales, Australia. It was designed by Henry Ginn, Edmund Blacket and built from 1840 to 1846 by Edward Flood and George Patton. It is also known as Holy Trinity Anglican Church and Hall. The property is owned by Anglican Church Property Trust and was added to the New South Wales State Heritage Register on 2 April 1999.

The Justice and Police Museum is a heritage-listed former water police station, offices and courthouse and now justice and police museum located at 4-8 Phillip Street on the corner of Albert Street, in the Sydney central business district in the City of Sydney local government area of New South Wales, Australia. It was designed by Edmund Blacket, Alexander Dawson and James Barnet and built from 1854 to 1886. It is also known as Police Station & Law Courts (former) and Traffic Court. The property is owned by the Department of Justice, a department of the Government of New South Wales. It was added to the New South Wales State Heritage Register on 2 April 1999.

The Darlinghurst Courthouse is a heritage-listed courthouse building located adjacent to Taylor Square on Oxford Street in the inner city Sydney suburb of Darlinghurst in the City of Sydney local government area of New South Wales, Australia. Constructed in the Old Colonial Grecian style based on original designs by Colonial Architect, Mortimer Lewis, the building structure was completed in 1880 under the supervision of Lewis's successor, James Barnet. It was added to the New South Wales State Heritage Register on 2 April 1999.

St Stephen's Anglican Church is a heritage-listed Anglican church and cemetery at 187–189 Church Street, Newtown, Inner West Council, Sydney New South Wales, Australia. It was designed by Edmund Blacket and built from 1871 to 1874 by George Dowling and Robert Kirkham. The church is also known as St Stephen's Church Of England. It was added to the New South Wales State Heritage Register on 2 April 1999.

Pyrmont Post Office is a heritage-listed former post office and now bank branch office located at 148 Harris Street, in the inner city Sydney suburb of Pyrmont in the City of Sydney local government area of New South Wales, Australia. It was designed by the Government Architect’s Office under Walter Liberty Vernon. The property is owned by Australia Post, an agency of the Commonwealth Government of Australia. It was added to the Australian Commonwealth Heritage List on 22 June 2004 and to the New South Wales State Heritage Register on 22 December 2000.

St John the Evangelist Church is a heritage-listed Presbyterian church located at Main Street, Wallerawang, City of Lithgow, New South Wales, Australia. It was designed by Edmund Blacket and Blacket and Sons, and built from 1880 to 1881 by George Donald. It is also known as the Church of St. John the Evangelist. It was added to the New South Wales State Heritage Register on 10 September 2004.

St John's Anglican Church and Macquarie Schoolhouse is a heritage-listed Anglican church building and church hall located at 43-43a Macquarie Road, Wilberforce, City of Hawkesbury, New South Wales, Australia. The church was designed by Edmund Blacket and built from 1819 to 1859 by James Atkinson, senior; and the schoolhouse was built by John Brabyn. The church is also known as the St. John's (Blacket) Church, while the hall is also known as the Macquarie Schoolhouse/Chapel and the Wilberforce Schoolhouse. It was added to the New South Wales State Heritage Register on 20 August 2010.

Thomas Vallance Wran was an English born Ruskinian-Romanesque sculptor, who arrived in Australia in 1870 aged thirty-eight, and spent his remaining years working with three of Sydney's leading architects on major institutional monuments. His architectural sculpture is remarkable for its three-dimensional force, creativity, and the invention of an indigenous ornament.

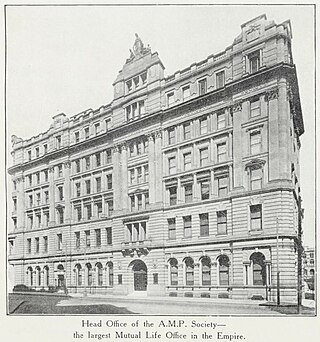

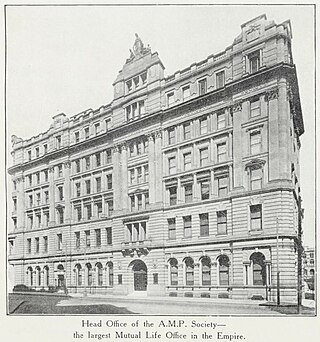

The Australian Mutual Provident Society Head Office was a landmark office building at 87 Pitt Street, bounded by Bond Street and Curtin Place in the central business district of Sydney. The first AMP head office building on this site was completed in 1878 and designed in the renaissance mannerist style by George Allen Mansfield. This building was substantially rebuilt and expanded in 1909–1912 in the Free Classical style by Ernest Alfred Scott. This building was the head office of the Australian Mutual Provident Society from 1878 until 1962, when the new AMP Building at Circular Quay was completed. The former head office building was demolished in September 1962 to make way for the landmark modernist Australia Square development by Lend Lease/Civil & Civic and designed by Harry Seidler.