Related Research Articles

In the broader context of racism in the United States, mass racial violence in the United States consists of ethnic conflicts and race riots, along with such events as:

Tallahassee is the capital city of the U.S. state of Florida. It is the county seat and only incorporated municipality in Leon County. Tallahassee became the capital of Florida, then the Florida Territory, in 1824. In 2022, the population was 201,731, making it the eighth-most populous city in the state of Florida. The population of the Tallahassee metropolitan area was 390,992 as of 2022. Tallahassee is the largest city in the Florida Big Bend and Florida Panhandle region, and the main center for trade and agriculture in the Florida Big Bend and Southwest Georgia regions.

Jackson County is a county located in the U.S. state of Florida, on its northwestern border with Alabama. As of the 2020 census, the population was 47,319. Its county seat is Marianna.

Leon County is a county in the Panhandle of the U.S. state of Florida. It was named after the Spanish explorer Juan Ponce de León. As of the 2020 census, the population was 292,198.

Orange County is a county located in Central Florida, and as of the 2020 census, its population was 1,429,908 making it Florida's fifth-most populous county. Its county seat is Orlando, the core of the Orlando metropolitan area, which had a population of 2.67 million in 2020.

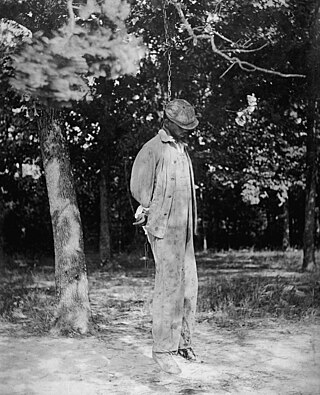

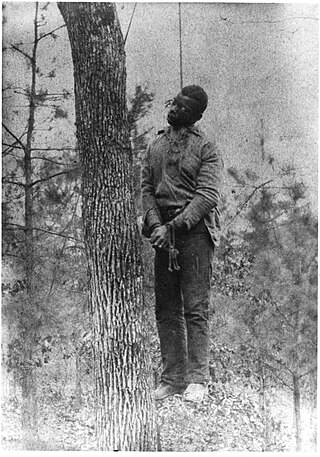

Lynching is an extrajudicial killing by a group. It is most often used to characterize informal public executions by a mob in order to punish an alleged transgressor, punish a convicted transgressor, or intimidate people. It can also be an extreme form of informal group social control, and it is often conducted with the display of a public spectacle for maximum intimidation. Instances of lynchings and similar mob violence can be found in every society.

Quincy is a city in and the county seat of Gadsden County, Florida, United States. Quincy is part of the Tallahassee metropolitan area. The population was 7,970 as of the 2020 census.

Marianna is a city in and the county seat of Jackson County, Florida, United States, and it is home to Chipola College. The official nickname of Marianna is "The City of Southern Charm". The population was 6,245 at the 2020 census.

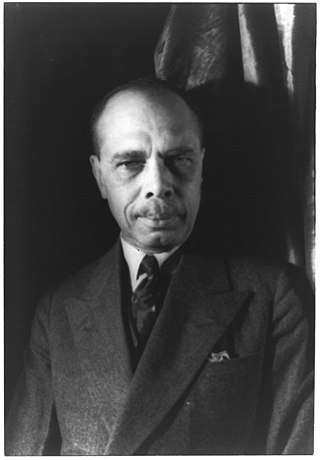

James Weldon Johnson was an American writer and civil rights activist. He was married to civil rights activist Grace Nail Johnson. Johnson was a leader of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), where he started working in 1917. In 1920, he was chosen as executive secretary of the organization, effectively the operating officer. He served in that position from 1920 to 1930. Johnson established his reputation as a writer, and was known during the Harlem Renaissance for his poems, novel and anthologies collecting both poems and spirituals of Black culture. He wrote the lyrics for "Lift Every Voice and Sing", which later became known as the Black National Anthem, the music being written by his younger brother, composer J. Rosamond Johnson.

Florida State University is a public research university in Tallahassee, Florida, United States. It is a senior member of the State University System of Florida. Chartered in 1851, it is located on Florida's oldest continuous site of higher education.

Florida Agricultural and Mechanical University (FAMU), commonly known as Florida A&M, is a public historically black land-grant university in Tallahassee, Florida. Founded in 1887, It is the third largest historically black university in the United States by enrollment and the only public historically black university in Florida. It is a member institution of the State University System of Florida, as well as one of the state's land grant universities, and is accredited to award baccalaureate, master's and doctoral degrees by the Commission on Colleges of the Southern Association of Colleges and Schools.

Florida Memorial University is a private historically black college in Miami Gardens, Florida. It is a member of the United Negro College Fund and historically related to Baptists although it claims a focus on broader Christianity.

Lynching was the widespread occurrence of extrajudicial killings which began in the United States' pre–Civil War South in the 1830s and ended during the civil rights movement in the 1950s and 1960s. Although the victims of lynchings were members of various ethnicities, after roughly 4 million enslaved African Americans were emancipated, they became the primary targets of white Southerners. Lynchings in the U.S. reached their height from the 1890s to the 1920s, and they primarily victimized ethnic minorities. Most of the lynchings occurred in the American South, as the majority of African Americans lived there, but racially motivated lynchings also occurred in the Midwest and border states. In 1891, the largest single mass lynching in American history was perpetrated in New Orleans against Italian immigrants.

The history of Tallahassee, Florida, much like the history of Leon County, dates back to the settlement of the Americas. Beginning in the 16th century, the region was colonized by Europeans, becoming part of Spanish Florida. In 1819, the Adams–Onís Treaty ceded Spanish Florida, including modern-day Tallahassee, to the United States. Tallahassee became a city and the state capital of Florida in 1821; the American takeover led to the settlements' rapid expansion as growing numbers of cotton plantations began to spring up nearby, increasing Tallahassees' population significantly.

The National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) is a civil rights organization in the United States, formed in 1909 as an interracial endeavor to advance justice for African Americans by a group including W. E. B. Du Bois, Mary White Ovington, Moorfield Storey, Ida B. Wells, Lillian Wald, and Henry Moskowitz. Over the years, leaders of the organization have included Thurgood Marshall and Roy Wilkins.

The Ocoee massacre was a mass racial violence event that saw a white mob attack numerous African-American residents in the northern parts of Ocoee, Florida, a town located in Orange County near Orlando. Previously inhabited by the Seminoles, Ocoee was the home to 255 African-American residents and 560 white residents according to the 1920 Census. The massacre took place on November 2, 1920, the day of the U.S. presidential election leaving a lasting political, but also community impact, as the 1930 census shows 1,180 whites, 11 Native Americans, and 2 African Americans (0.2%).

Willie James Howard was a 15-year-old African-American living in Live Oak, Suwannee County, Florida. He was lynched for having given Christmas cards to all his co-workers at the Van Priest Dime Store, including Cynthia Goff, a white girl, followed by a letter to her on New Year's Day.

Cellos Harrison was an African American man in Marianna, Florida who was lynched on June 16, 1943 after being rearrested when his murder conviction was overturned by the Supreme Court of Florida because his confession was obtained under duress. He was twice convicted by an all-white jury of murdering a white man who was working as a gas station attendant and store clerk. State and federal investigations were launched into the lynching but no one was ever indicted or convicted. A decade earlier Claude Neal was lynched in Marianna. The area was also wrought by a wave of violence against African Americans and Republicans during the Reconstruction Era after the American Civil War in what is known as the Jackson County War.

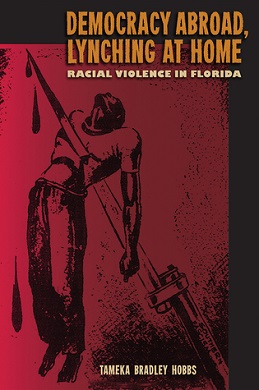

Democracy Abroad, Lynching At Home: Racial Violence In Florida is a 2015 history book by Tameka Bradley Hobbs that discusses how lynchings have changed in the United States, with a focus on the mid 20th century Florida lynchings of Arthur C. Williams, Cellos Harrison, Willie James Howard, and Jesse James Payne. The book won a 2015 Bronze Florida Book Award and the 2016 Harry T. and Harriette V. Moore Award from the Florida Historical Society.

References

- ↑ Libraries, Broward County. "Dr. Tameka Bradley Hobbs Selected as New Manager of African American Research Library and Cultural Center". www.prnewswire.com (Press release). Retrieved 2023-09-03.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Benowitz, Shayne (October 22, 2020). "These rising local power players are advancing the community through activism, education, and more". Miami Herald . Archived from the original on 7 April 2021. Retrieved 15 September 2021.

- 1 2 Davidson-Hiers, CD (April 8, 2017). "Author of book on lynching talks history at Word of South". Tallahassee Democrat . Archived from the original on 15 September 2021. Retrieved 15 September 2021.

- ↑ "Documentary reopens old wounds from Jim Crow-era killing". CBS News . Associated Press. January 1, 2015. Archived from the original on 16 September 2021. Retrieved 16 September 2021.

- 1 2 3 4 "Dr. Tameka Bradley-Hobbs". NSU Florida. Nova Southeastern University. Archived from the original on 17 September 2021. Retrieved 17 September 2021.

- 1 2 Hassanein, Nada (June 13, 2018). "'Painful history': Remembering Leon County's lynching victims". Tallahassee Democrat . Archived from the original on 15 September 2021. Retrieved 15 September 2021.

- 1 2 Hollinger, Michelle (March 10, 2016). "Hobbs wins bronze medal for book on lynching". South Florida Times. Archived from the original on 16 September 2021. Retrieved 16 September 2021.

- ↑ Vandiver, Margaret (2005). Lethal Punishment: Lynchings and Legal Executions in the South. Rutgers University Press. p. 257. ISBN 9780813541068.

- ↑ Holmes, Anna (May 14, 2015). "The Underground Art of the Insult". The New York Times Magazine . Archived from the original on 16 September 2021. Retrieved 16 September 2021.

- ↑ "Three Tallahassee writers win Florida Book Awards". Tallahassee Democrat . March 5, 2016. Archived from the original on 15 September 2021. Retrieved 15 September 2021.

- ↑ Mari N. Crabtree (November 3, 2016). "Review of Democracy Abroad, Lynching at Home: Racial Violence in Florida by Tameka Bradley Hobbs". Journal of Southern History . 82 (4): 950–951. doi:10.1353/soh.2016.0286. S2CID 159674568. Archived from the original on April 4, 2019. Retrieved September 16, 2021.

With so much of the literature on lynching focused on white southerners, her interviews with African American survivors provide a poignant and, at times, gut-wrenching glimpse into the intergenerational trauma of lynching.

- ↑ Michael J. Pfeifer (October 4, 2016). "Review of Tameka Bradley Hobbs. Democracy Abroad, Lynching at Home: Racial Violence in Florida". The American Historical Review . 121 (4). American Historical Association: 1309–1310. doi:10.1093/ahr/121.4.1309. Archived from the original on September 17, 2021. Retrieved September 16, 2021.

Throughout her narrative and especially in a powerful epilogue, Hobbs provides a highly valuable analysis of the effects of the four lynchings on the families of the lynching victims as well as on local black communities. For the families and descendants of lynching victims, migration and broken family relationships often ensued, as did painful silences; for the larger African American community in localities, oral histories reconstructed events in instrumentalist ways that stressed the dangerously unjust ways of white supremacy.

- ↑ Taylor, David (June 11, 2021). "Capturing the Stories of America in a Crisis". Davidson Journal Magazine. Davidson College. Archived from the original on 16 September 2021. Retrieved 16 September 2021.

- ↑ "FMU to launch the South Florida Social Justice Common Read". South Florida Times. November 12, 2020. Archived from the original on 15 September 2021. Retrieved 15 September 2021.

- ↑ Fortin, Jacey (February 28, 2020). "Congress Moves to Make Lynching a Federal Crime After 120 Years of Failure". The New York Times . Archived from the original on 11 September 2021. Retrieved 16 September 2021.

- ↑ "Dr. Tameka Bradley Hobbs Appointed Inaugural Executive Director of the A. Philip Randolph Institute for Law, Race, Social Justice, and Economic Policy". Edward Waters University. March 25, 2022. Retrieved 9 June 2022.

- ↑ Hoffman, Michael (June 7, 2015). "Book review: 'After War Times: An African American Childhood in Reconstruction-era Florida' by T. Thomas Fortune". The Florida Times-Union . Archived from the original on 16 September 2021. Retrieved 16 September 2021.

- ↑ "Congratulations to our 2015 Florida Book Awards Winners!". The Florida Book Awards. Archived from the original on 16 June 2021. Retrieved 15 September 2021.

- ↑ "End Notes: Florida Historical Society News". The Florida Historical Quarterly . 94 (4). Florida Historical Society: 698. Spring 2016. JSTOR 24769245. Archived from the original on 15 September 2021. Retrieved 15 September 2021.