The demographics of Malaysia are represented by the multiple ethnic groups that exist in the country. Malaysia's population, according to the 2010 census, is 28,334,000 including non-citizens, which makes it the 42nd most populated country in the world. Of these, 5.72 million live in East Malaysia and 22.5 million live in Peninsular Malaysia. The population distribution is uneven, with some 79% of its citizens concentrated in Peninsular Malaysia, which has an area of 131,598 square kilometres (50,810.27 sq mi), constituting under 40% of the total area of Malaysia.

Education in Malaysia is overseen by the Ministry of Education. Although education is the responsibility of the Federal Government, each state and federal territory has an Education Department to co-ordinate educational matters in its territory. The main legislation governing education is the Education Act 1996.

A medium of instruction is a language used in teaching. It may or may not be the official language of the country or territory. If the first language of students is different from the official language, it may be used as the medium of instruction for part or all of schooling. Bilingual education or multilingual education may involve the use of more than one language of instruction. UNESCO considers that "providing education in a child's mother tongue is indeed a critical issue". In post-secondary, university and special education settings, content may often be taught in a language that is not spoken in the students' homes. This is referred to as content based learning or content and language integrated learning (CLIL). In situations where the medium of instruction of academic disciplines is English when it is not the students' first language, the phenomenon is referred to as English-medium instruction (EMI).

Sekolah Dato' Abdul Razak is a premiere, Sekolah Berasrama Penuh for boys in Seremban, Negeri Sembilan, Malaysia. It is one of the most prestigious schools, selecting the best students in the country and is named after Abdul Razak Hussein.

Sekolah Tuanku Abdul Rahman is an all-boys fully residential school in Malaysia funded by the Government of Malaysia. Named after the first Yang di-Pertuan Agong (King) of the Federation of Malaya, Almarhum Seri Paduka Baginda Tuanku Abdul Rahman ibni Almarhum Tuanku Muhammad, it is located in Ipoh, Perak. The school started at an army camp in Baeza Avenue. Formerly known as Malay Secondary School, the school was built by the Malayan government in 1957. In 2011, the school was awarded with the Sekolah Berprestasi Tinggi or High Performance School title, a title awarded to schools in Malaysia that have met stringent criteria including academic achievement, strength of alumni, international recognition, network and linkages.

The Sijil Pelajaran Malaysia (SPM), or the Malaysian Certificate of Education, is a national examination sat for by all fifth-form secondary school students in Malaysia. It is the equivalent of the General Certificate of Secondary Education (GCSE) of England, Wales and Northern Ireland; the Nationals 4/5 of Scotland; and the GCE Ordinary Level of the Commonwealth of Nations. It is the leaving examination of the eleventh grade of schooling.

A Chinese independent high school is a type of private high school in Malaysia. They provide secondary education in the Chinese language as the continuation of the primary education in Chinese national-type primary schools. The main medium of instruction in these schools is Mandarin Chinese using simplified Chinese characters.

The Barnes Report was a British proposal put forward in 1951 to develop a national education system in British Malaya. The Fenn-Wu Report, favoured by the Chinese, did not meet with Malay approval. In the end, the Barnes Report's recommendations for English-medium "national schools" were implemented by the 1952 Education Ordinance, over vocal Chinese protests, who were upset by the lack of provision for non-Malay vernacular schools.

La Salle School, Klang is a boys' mission school in Klang, Selangor, Malaysia. It is located at Persiaran Raja Muda Musa, Klang and neighbours three other schools: Hin Hua High School (Private), SMK Tengku Ampuan Rahimah, and SK (1)&(2) Simpang lima.

Harold Ambrose Robinson Cheeseman was an English educator who was founder of the Scouting movement in the Malaysian state of Penang, at the Penang Free School on 27 March 1915, and in the state of Johor at the English College Johore Bahru in 1928.

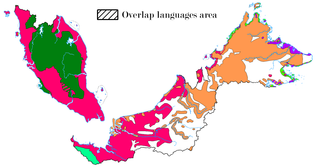

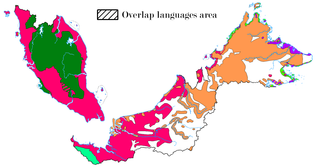

The indigenous languages of Malaysia belong to the Mon-Khmer and Malayo-Polynesian families. The national, or official, language is Malay which is the mother tongue of the majority Malay ethnic group. The main ethnic groups within Malaysia are the Malay people, Han Chinese people and Tamil people, with many other ethnic groups represented in smaller numbers, each with its own languages. The largest native languages spoken in East Malaysia are the Iban, Dusunic, and Kadazan languages. English is widely understood and spoken within the urban areas of the country; the English language is a compulsory subject in primary and secondary education. It is also the main medium of instruction within most private colleges and private universities. English may take precedence over Malay in certain official contexts as provided for by the National Language Act, especially in the states of Sabah and Sarawak, where it may be the official working language. Furthermore, the law of Malaysia is commonly taught and read in English, as the unwritten laws of Malaysia continues to be partially derived from pre-1957 English common law, which is a legacy of past British colonisation of the constituents forming Malaysia. In addition, authoritative versions of constitutional law and statutory law are continuously available in both Malay and English.

Sunny Hill School is a non-profit, private education institution located in Kuching, the capital of Sarawak, Malaysia. It is operated by the Seventh-day Adventist Mission of Sarawak and educates children from ages 2/3 (Nursery) to 17/18.

Sekolah Berasrama Penuh (SBP) or Fully Residential School is a school system established in Malaysia to nurture outstanding students to excel in academics and extracurricular activities. Since 2008, SBPs are directly administered by Fully Residential and Excellent Schools Management Division, Ministry of Education.

Sekolah Menengah Kebangsaan Taman Tun Dr. Ismail or SMKTTDI is a secondary school located along Jalan Leong Yew Koh, in Taman Tun Dr. Ismail, a main township in Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia. It was founded in 1980.

The Razak Report is a Malayan educational proposal written in the 1956. Named after the then Education Minister, Tun Abdul Razak, its goal was to reform the education system in Malaya. The report was incorporated into the Section 3 of the Education Ordinance of 1957 and served the basis of the educational framework for independent Malaya and eventually Malaysia. Private schools were nationalized, education was expanded at all levels and was heavily subsidized, and indeed the growth in enrollment rate again accelerated.

Pengajaran dan Pembelajaran Sains dan Matematik Dalam Bahasa Inggeris (PPSMI) is a government policy aimed at improving the command of the English language among pupils at primary and secondary schools in Malaysia. In accordance to this policy, the Science and Mathematics subjects are taught in the English medium as opposed to the Malay medium used before. This policy was introduced in 2003 by the then-Prime Minister of Malaysia, Mahathir Mohamad. PPSMI has been the subject of debate among academics, politicians and the public alike, which culminated to the announcement of the policy's reversal in 2012 by the Deputy Prime Minister, Muhyiddin Yassin.

Malaysian Indians or Indian Malaysians are Malaysian citizens of Indian or South Asian ancestry. They now form the third-largest group in Malaysia, after the Malays and the Chinese. Most are descendants of those who migrated from India to British Malaya from the mid-19th to the mid-20th centuries. Most Malaysian Indians are ethnic Tamils; smaller groups include the Malayalees, Telugus and Punjabis. Malaysian Indians form the fifth-largest community of Overseas Indians in the world. In Malaysia, they represent the third-largest group, constituting 7% of the Malaysian population, after the ethnic Malays and the Chinese. They are usually referred to simply as "Indians" in English, Orang India in Malay, "Yin du ren" in Chinese.

Singapore embraces an English-based bilingual education system. Students are taught subject-matter curriculum with English as the medium of instruction, while the official mother tongue of each student - Mandarin Chinese for Chinese, Malay for Malays and Tamil for South Indians – is taught as a second language. Additionally, Higher Mother Tongue (HMT) is offered as an additional and optional examinable subject to those with the interest and ability to handle the higher standards demanded by HMT. The content taught to students in HMT is of a higher level of difficulty and is more in-depth so as to help students achieve a higher proficiency in their respective mother tongues. The choice to take up HMT is offered to students in the Primary and Secondary level. Thereafter, in junior colleges, students who took HMT at the secondary level have the choice to opt out of mother tongue classes entirely. Campaigns by the government to encourage the use of official languages instead of home languages have been largely successful, although English seems to be becoming the dominant language in most homes. To date, many campaigns and programmes have been launched to promote the learning and use of mother tongue languages in Singapore. High ability students may take a third language if they choose to do so.

Education in Brunei is provided or regulated by the Government of Brunei through the Ministry of Education and the Ministry of Religious Affairs. The former manages most of the government and private schools in the country where as the latter specifically administers government schools which provide the ugama or Islamic religious education.

Malaysian Malayalees, also known as Malayalee Malaysians, are people of Malayali descent who were born in or immigrated to Malaysia from the Malayalam speaking regions of Kerala. They are the second largest Indian ethnic group, making up approximately 15% of the Malaysian Indian population. The bulk of Malaysian Malayali migration began during the British Raj, when the British facilitated the migration of Indian workers to work in plantations, but unlike the majority Tamils, the vast majority of the Malayalis were recruited as supervisors in the oil palm estates that followed the kangani system, and some were into trading and small businesses with a significant proportion of them running groceries or restaurants. Over 90% of the Malayalee population in Malaysia are Malaysian citizens.