Fatah, formerly the Palestinian National Liberation Movement, is a Palestinian nationalist and social democratic political party. It is the largest faction of the confederated multi-party Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO) and the second-largest party in the Palestinian Legislative Council (PLC). Mahmoud Abbas, the President of the Palestinian Authority, is the chairman of Fatah.

Yasser Arafat was a Palestinian political leader. He was chairman of the Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO) from 1969 to 2004 and president of the Palestinian National Authority (PNA) from 1994 to 2004. Ideologically an Arab nationalist and a socialist, Arafat was a founding member of the Fatah political party, which he led from 1959 until 2004.

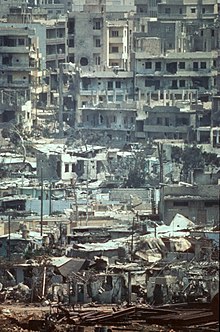

The Sabra and Shatila massacre was the 16–18 September 1982 killings of between 460 and 3,500 civilians—mostly Palestinians and Lebanese Shias—in the city of Beirut during the Lebanese Civil War. It was perpetrated by the Lebanese Forces, one of the main Christian militias in Lebanon, and supported by the Israel Defense Forces (IDF) that had surrounded Beirut's Sabra neighbourhood and the adjacent Shatila refugee camp.

The Lebanese Civil War was a multifaceted armed conflict that took place from 1975 to 1990. It resulted in an estimated 150,000 fatalities and also led to the exodus of almost one million people from Lebanon.

Dany Chamoun was a prominent Lebanese politician. A Maronite Christian, the younger son of former President Camille Chamoun and brother of Dory Chamoun, Chamoun was also a politician in his own right.

The Guardians of the Cedars was a far-right ultranationalist Lebanese party and former militia in Lebanon. It was formed by Étienne Saqr and others along with the Lebanese Renewal Party in the early 1970s. It operated in the Lebanese Civil War under the slogan: Lebanon, at your service. The militia was explicitly Anti-Palestinian, and gained a reputation for brutality against Palestinian fighters and civilians.

As-Sa'iqa officially known as Vanguard for the Popular Liberation War - Lightning Forces, is a Palestinian Ba'athist political and military faction created and controlled by Syria. It is linked to the Palestinian branch of the Syrian-led Ba'ath Party, and is a member of the broader Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO), although it is no longer active in the organization. Its Secretary-General is Dr. Mohammed Qeis.

The War of the Camps, was a subconflict within the 1984–1990 phase of the Lebanese Civil War, in which the Palestinian refugee camps in Beirut were besieged by the Shia Amal militia.

The Lebanese Forces is a Lebanese Christian-based political party and former militia during the Lebanese Civil War. It currently holds 19 of the 128 seats in Lebanon's parliament and is therefore the largest party in parliament.

The Damour massacre took place on 20 January 1976, during the 1975–1990 Lebanese Civil War. Damour, a Maronite Christian town on the main highway south of Beirut, was attacked by left-wing militants of the Palestine Liberation Organisation and as-Sa'iqa. Many of its people died in battle or in the massacre that followed, and the others were forced to flee. According to Robert Fisk, the town was the first to be subject to ethnic cleansing in the Lebanese Civil War. The massacre was in retaliation to the Karantina massacre by the Phalangists.

The Palestine Liberation Army is ostensibly the military wing of the Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO), set up at the 1964 Arab League summit held in Alexandria, Egypt, with the mission of fighting Israel. However, it has never been under effective PLO control, but rather it has been controlled by its various host governments, usually Syria. Even though it initially operated in several countries, the present-day PLA is only active in Syria and recruits male Palestinian refugees.

Fatah al-Intifada is a Palestinian militant faction founded by Said Muragha, better known as Abu Musa. Officially it refers to itself as the Palestinian National Liberation Movement - "Fatah", the identical name of the major Fatah movement. Fatah al-Intifada is not part of the Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO).

The Karantina massacre took place on January 18, 1976, early in the Lebanese Civil War. La Quarantaine, known in Arabic as Karantina, was a Muslim-inhabited district in mostly Christian East Beirut controlled by forces of the Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO), and inhabited by Palestinians, Kurds, Syrians, Armenians and Lebanese Shiites. The fighting and subsequent killings also involved an old quarantine area near the port and nearby Maslakh quarter. According to then-Washington Post-correspondent Jonathan Randal, "Many Lebanese Muslim men and boys were rounded up and separated from the women and children and massacred," while the women and young girls were violently raped and robbed.

The Lebanese Youth Movement – LYM (Arabic: حركة الشباب اللبنانية | Harakat al-Shabab al-Lubnaniyya), also known as the Maroun Khoury Group (MKG), was a Christian far-right militia which fought in the 1975-77 phase of the Lebanese Civil War.

Bachir Pierre Gemayel was a Lebanese militia commander who led the Lebanese Forces, the military wing of the Kataeb Party in the Lebanese Civil War and was elected President of Lebanon in 1982.

The Tyous Team of Commandos – TTC or simply Tyous for short, was a small far-right Christian militia which fought in the 1975-78 phase of the Lebanese Civil War.

The Kataeb Regulatory Forces – KRF or Forces Régulatoires des Kataeb (FRK) in French, were the military wing of the right-wing Lebanese Christian Kataeb Party, otherwise known as the 'Phalange', from 1961 to 1977. The Kataeb militia, which fought in the early years of the Lebanese Civil War, was the predecessor of the Lebanese Forces. The militia was also involved in massacres against Palestinians in Beirut, Karantina and Tel al-Zaatar.

The Palestinian insurgency in South Lebanon was a multi-sided armed conflict initiated by Palestinian militants against Israel in 1968 and against Lebanese Christian militias in the mid-1970s. It served as a major catalyst for the outbreak of the Lebanese Civil War in 1975. Fighting between the Palestinians and the Christian militias lasted until the Israeli invasion of Lebanon in 1982, which led to the expulsion of the Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO) from Lebanese territory. While the PLO relocated to Tunisia in the aftermath of Israel's invasion, other Palestinian militant factions, such as the Syria-based PFLP–GC, continued to carry out low-level operations from Syrian-occupied Lebanon. After 1982, the insurgency is considered to have faded in light of the inter-Lebanese Mountain War and the Israel–Hezbollah conflict, the latter of which took place for the duration of the Israeli occupation of South Lebanon.

The Palestinian National Salvation Front (PNSF) was a coalition of Palestinian factions. The creation of the Palestinian National Salvation Front was announced on March 25, 1985, by Khalid al-Fahum. The front consisted of the PFLP, PFLP-GC, as-Sa'iqa, the Palestinian Popular Struggle Front, the Palestinian Liberation Front and Fatah al-Intifada. The Front was founded in reaction to the Amman Accord between Yasser Arafat and King Hussein of Jordan.

The Battle of Tripoli was a major battle during the middle of the Lebanese Civil War in late 1983. It took place in the northern coastal city of Tripoli between pro-Syrian Palestinian militant factions and the Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO) led by Yassir Arafat. It resulted in the withdrawal of PLO and mostly ended their involvement in the war.