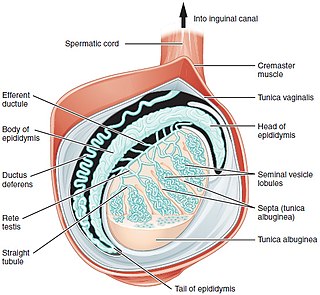

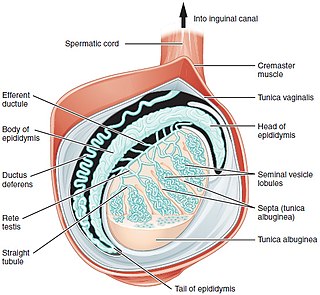

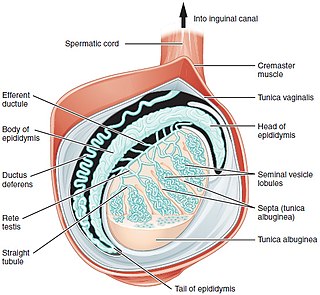

A testicle or testis is the male gonad in all bilaterians, including humans. It is homologous to the female ovary. The functions of the testicles are to produce both sperm and androgens, primarily testosterone. Testosterone release is controlled by the anterior pituitary luteinizing hormone, whereas sperm production is controlled both by the anterior pituitary follicle-stimulating hormone and gonadal testosterone.

Cryptorchidism, also known as undescended testis, is the failure of one or both testes to descend into the scrotum. The word is from Greek κρυπτός 'hidden' and ὄρχις 'testicle'. It is the most common birth defect of the male genital tract. About 3% of full-term and 30% of premature infant boys are born with at least one undescended testis. However, about 80% of cryptorchid testes descend by the first year of life, making the true incidence of cryptorchidism around 1% overall. Cryptorchidism may develop after infancy, sometimes as late as young adulthood, but that is exceptional.

Delayed puberty is when a person lacks or has incomplete development of specific sexual characteristics past the usual age of onset of puberty. The person may have no physical or hormonal signs that puberty has begun. In the United States, girls are considered to have delayed puberty if they lack breast development by age 13 or have not started menstruating by age 15. Boys are considered to have delayed puberty if they lack enlargement of the testicles by age 14. Delayed puberty affects about 2% of adolescents.

Hypogonadism means diminished functional activity of the gonads—the testicles or the ovaries—that may result in diminished production of sex hormones. Low androgen levels are referred to as hypoandrogenism and low estrogen as hypoestrogenism. These are responsible for the observed signs and symptoms in both males and females.

Kallmann syndrome (KS) is a genetic disorder that prevents a person from starting or fully completing puberty. Kallmann syndrome is a form of a group of conditions termed hypogonadotropic hypogonadism. To distinguish it from other forms of hypogonadotropic hypogonadism, Kallmann syndrome has the additional symptom of a total lack of sense of smell (anosmia) or a reduced sense of smell. If left untreated, people will have poorly defined secondary sexual characteristics, show signs of hypogonadism, almost invariably are infertile and are at increased risk of developing osteoporosis. A range of other physical symptoms affecting the face, hands and skeletal system can also occur.

Spermatocele is a fluid-filled cyst that develops in the epididymis. The fluid is usually a clear or milky white color and may contain sperm. Spermatoceles are typically filled with spermatozoa and they can vary in size from several millimeters to many centimeters. Small spermatoceles are relatively common, occurring in an estimated 30 percent of males. They are generally not painful. However, some people may experience discomfort such as a dull pain in the scrotum from larger spermatoceles. They are not cancerous, nor do they cause an increased risk of testicular cancer. Additionally, unlike varicoceles, they do not reduce fertility.

A varicocele is, in a male person, an abnormal enlargement of the pampiniform venous plexus in the scrotum; in a female person, it is an abnormal painful swelling to the embryologically identical pampiniform venous plexus; it is more commonly called pelvic compression syndrome. In the male varicocele, this plexus of veins drains blood from the testicles back to the heart. The vessels originate in the abdomen and course down through the inguinal canal as part of the spermatic cord on their way to the testis. Varicoceles occur in around 15% to 20% of all men. The incidence of varicocele increase with age.

Azoospermia is the medical condition of a man whose semen contains no sperm. It is associated with male infertility, but many forms are amenable to medical treatment. In humans, azoospermia affects about 1% of the male population and may be seen in up to 20% of male infertility situations in Canada.

Terms oligospermia, oligozoospermia, and low sperm count refer to semen with a low concentration of sperm and is a common finding in male infertility. Often semen with a decreased sperm concentration may also show significant abnormalities in sperm morphology and motility. There has been interest in replacing the descriptive terms used in semen analysis with more quantitative information.

Hypospermia is a condition in which a man has an unusually low ejaculate volume, less than 1.5 mL. It is the opposite of hyperspermia, which is a semen volume of more than 5.5 mL. It should not be confused with oligospermia, which means low sperm count. Normal ejaculate when a man is not drained from prior sex and is suitably aroused is around 1.5–6 mL, although this varies greatly with mood, physical condition, and sexual activity. Of this, around 1% by volume is sperm cells. The U.S.-based National Institutes of Health defines hypospermia as a semen volume lower than 2 mL on at least two semen analyses.

Male infertility refers to a sexually mature male's inability to impregnate a fertile female. In humans, it accounts for 40–50% of infertility. It affects approximately 7% of all men. Male infertility is commonly due to deficiencies in the semen, and semen quality is used as a surrogate measure of male fecundity. More recently, advance sperm analyses that examine intracellular sperm components are being developed.

Testicular sperm extraction (TESE) is a surgical procedure in which a small portion of tissue is removed from the testicle and any viable sperm cells from that tissue are extracted for use in further procedures, most commonly intracytoplasmic sperm injection (ICSI) as part of in vitro fertilisation (IVF). TESE is often recommended to patients who cannot produce sperm by ejaculation due to azoospermia.

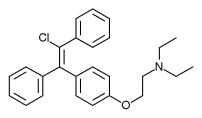

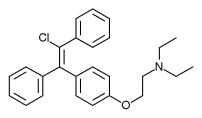

Enclomifene (INNTooltip International Nonproprietary Name), or enclomiphene (USANTooltip United States Adopted Name), a nonsteroidal selective estrogen receptor modulator of the triphenylethylene group acts by antagonizing the estrogen receptor (ER) in the pituitary gland, which reduces negative feedback by estrogen on the hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal axis, thereby increasing gonadotropin secretion and hence gonadal production of testosterone. It is one of the two stereoisomers of clomifene, which itself is a mixture of 38% zuclomifene and 62% enclomifene. Enclomifene is the (E)-stereoisomer of clomifene, while zuclomifene is the (Z)-stereoisomer. Whereas zuclomifene is more estrogenic, enclomifene is more antiestrogenic. In accordance, unlike enclomifene, zuclomifene is antigonadotropic due to activation of the ER and reduces testosterone levels in men. As such, isomerically pure enclomifene is more favorable than clomifene as a progonadotropin for the treatment of male hypogonadism.

Orchiectomy is a surgical procedure in which one or both testicles are removed. The surgery can be performed for various reasons:

Hypergonadotropic hypogonadism (HH), also known as primary or peripheral/gonadal hypogonadism or primary gonadal failure, is a condition which is characterized by hypogonadism which is due to an impaired response of the gonads to the gonadotropins, follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) and luteinizing hormone (LH), and in turn a lack of sex steroid production. As compensation and the lack of negative feedback, gonadotropin levels are elevated. Individuals with HH have an intact and functioning hypothalamus and pituitary glands so they are still able to produce FSH and LH. HH may present as either congenital or acquired, but the majority of cases are of the former nature. HH can be treated with hormone replacement therapy.

Leydig cell hypoplasia (LCH), also known as Leydig cell agenesis, is a rare autosomal recessive genetic and endocrine syndrome affecting an estimated 1 in 1,000,000 genetic males. It is characterized by an inability of the body to respond to luteinizing hormone (LH), a gonadotropin which is normally responsible for signaling Leydig cells of the testicles to produce testosterone and other androgen sex hormones. The condition manifests itself as pseudohermaphroditism, hypergonadotropic hypogonadism, reduced or absent puberty, and infertility.

Gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) insensitivity also known as Isolated gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH)deficiency (IGD) is a rare autosomal recessive genetic and endocrine syndrome which is characterized by inactivating mutations of the gonadotropin-releasing hormone receptor (GnRHR) and thus an insensitivity of the receptor to gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH), resulting in a partial or complete loss of the ability of the gonads to synthesize the sex hormones. The condition manifests itself as isolated hypogonadotropic hypogonadism (IHH), presenting with symptoms such as delayed, reduced, or absent puberty, low or complete lack of libido, and infertility, and is the predominant cause of IHH when it does not present alongside anosmia.

Follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) insensitivity, or ovarian insensitivity to FSH in females, also referable to as ovarian follicle hypoplasia or granulosa cell hypoplasia in females, is a rare autosomal recessive genetic and endocrine syndrome affecting both females and males, with the former presenting with much greater severity of symptomatology. It is characterized by a resistance or complete insensitivity to the effects of follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH), a gonadotropin which is normally responsible for the stimulation of estrogen production by the ovaries in females and maintenance of fertility in both sexes. The condition manifests itself as hypergonadotropic hypogonadism, reduced or absent puberty, amenorrhea, and infertility in females, whereas males present merely with varying degrees of infertility and associated symptoms.

Androgen deficiency is a medical condition characterized by insufficient androgenic activity in the body. Androgen deficiency most commonly affects women, and is also called Female androgen insufficiency syndrome (FAIS), although it can happen in both sexes. Androgenic activity is mediated by androgens, and is dependent on various factors including androgen receptor abundance, sensitivity and function. Androgen deficiency is associated with lack of energy and motivation, depression, lack of desire (libido), and in more severe cases changes in secondary sex characteristics.

The side effects of radiotherapy on fertility are a growing concern to patients undergoing radiotherapy as cancer treatments. Radiotherapy is essential for certain cancer treatments and often is the first point of call for patients. Radiation can be divided into two categories: ionising radiation (IR) and non-ionising radiation (NIR). IR is more dangerous than NIR and a source of this radiation is X-rays used in medical procedures, for example in radiotherapy.