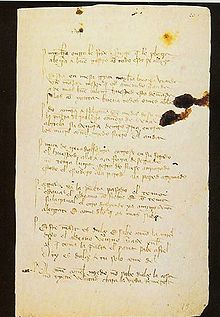

Juan Ruiz, known as the Archpriest of Hita, was a medieval Castilian poet. He is best known for his ribald, earthy poem, ElLibro de buen amor.

Mester de Clerecía is a Spanish literature genre that can be understood as an opposition and surpassing of Mester de Juglaría. It was cultivated in the 13th century by Spanish learned poets, usually clerics.

This article concerns poetry in Spain.

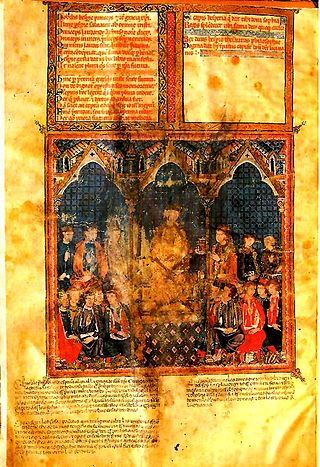

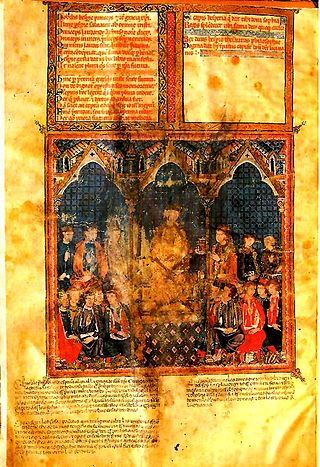

Don Juan Manuel was a Spanish medieval writer, nephew of Alfonso X of Castile, son of Manuel of Castile and Beatrice of Savoy. He inherited from his father the great Lordship of Villena, receiving the titles of Lord, Duke and lastly Prince of Villena. He married three times, choosing his wives for political and economic convenience, and worked to match his children with partners associated with royalty. Juan Manuel became one of the richest and most powerful men of his time, coining his own currency as the kings did. During his life, he was criticised for choosing literature as his vocation, an activity thought inferior for a nobleman of such prestige.

An Arabist is someone, often but not always from outside the Arab world, who specialises in the study of the Arabic language and culture.

Francisco "Patxi" Andión González was a Spanish singer-songwriter, musician and actor.

In Spain, Portugal and Latin American countries, a tuna is a group of university students in traditional university dress who play traditional instruments and sing serenades. The tradition originated in Spain and Portugal in the 13th century as a means of students to earn money or food. Nowadays students don't belong to a "tuna" for money or food; rather, they seek to keep a tradition alive, for fun, to travel a lot and to meet new people from other universities. A senior member of a tuna is a "tunante," but is usually known simply as a "tuno." The word “tuno” also refers to anyone who is a member of a tuna, although the first conceptualisation is more used among tunas. Newbies are known as "caloiros", "novatos" or "pardillos."

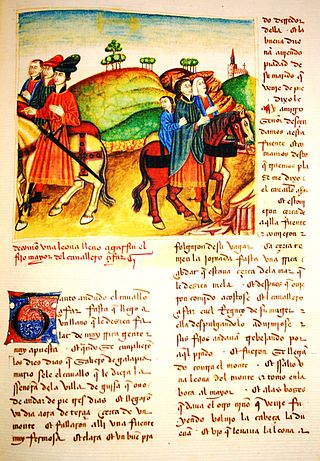

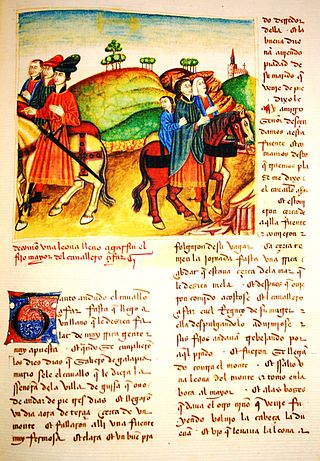

Pedro Tafur was a traveller, historian and writer from Castile. Born in Córdoba, to a branch of the noble house of Guzmán, Tafur traveled across three continents during the years 1436 to 1439. During the voyage, he participated in various battles, visited shrines, and rendered diplomatic services for Juan II of Castile. He visited the Moroccan coast, southern France, the Holy Land, Egypt, Rhodes, Cyprus, Tenedos, Trebizond, Caffa, and Constantinople. He also visited the Sinai Peninsula, where he met Niccolò Da Conti, who shared with Tafur information about southeastern Asia. Before returning to Spain, Tafur crossed central Europe and Italy.

Hita is a municipality in the comarca of La Alcarria, in the province of Guadalajara (province), Spain.

Eduardo Lemaitre Román was a prominent historian, writer, journalist and politician who lived in Cartagena, Colombia. He held the positions of Representative (1943), Senator (1950) and Governor (1962) of Colombia's Bolivar department. He also served as Ambassador to UNESCO.

Joan de Castellnou was a troubadour of the Consistori del Gay Saber active in Toulouse. He left behind five or six cansos, three vers, a dansa, a conselh, and a sirventes. His most famous works are non-lyric, however: a grammar (compendi) called Las flors del gay saber, estier dichas las Leys d'amors and a glossary (glosari) on the Doctrinal (1324) of his predecessor, Raimon de Cornet.

De vetula is a long 13th-century elegiac comedy written in Latin. It is pseudepigraphically signed "Ovidius", and in its time was attributed to the classical Latin poet Ovid. It consists of three books of hexameters, and was quoted by Roger Bacon. In its slight plot, the aging Ovid is duped by a go-between, and renounces love affairs. Its interest to modern readers lies in the discursive padding of the story.

Dorothy Sherman Severin AB, AM, PhD, FSA, OBE is Emeritus Professor of Literature at University of Liverpool and a Hispanist. Her research interests include cancioneros and La Celestina.

Rubén Caba, born in Madrid, is a Spanish novelist and essayist. Degrees in Law and in Philosophy at de Universidad Complutense de Madrid. And graduated in Sociology at Instituto de Estudios Políticos, Madrid.

The Estoria de España, also known in the 1906 edition of Ramón Menéndez Pidal as the Primera Crónica General, is a history book written on the initiative of Alfonso X of Castile "El Sabio", who was actively involved in the editing. It is believed to be the first extended history of Spain in Old Spanish, a West Iberian Romance language that forms part of the lineage from Vulgar Latin to modern Spanish. Many prior works were consulted in constructing this history.

Medieval Spanish literature consists of the corpus of literary works written in medieval Spanish between the beginning of the 13th and the end of the 15th century. Traditionally, the first and last works of this period are taken to be respectively the Cantar de Mio Cid, an epic poem whose manuscript dates from 1207, and La Celestina (1499), a work commonly described as transitional between the medieval period and the Renaissance.

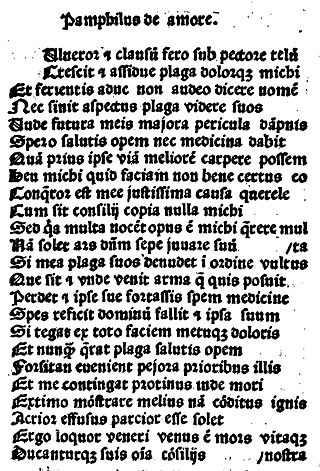

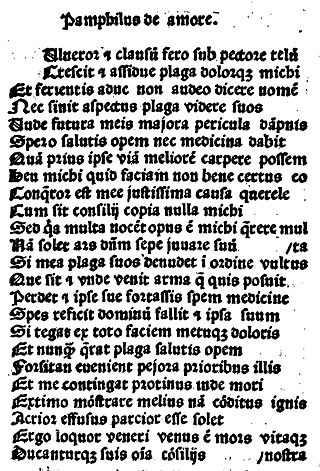

Pamphilus de amore is a 780-line, 12th-century Latin comedic play, probably composed in France, but possibly Spain. It was "one of the most influential and important of the many pseudo-Ovidian productions concerning the 'arts of Love'" in medieval Europe, and "the most famous and influential of the medieval elegiac comedies, especially in Spain". The protagonists are Pamphilus and Galatea, with Pamphilus seeking to woo her through a procuress.

The Guitarra morisca or Mandora medieval is a plucked string instrument. It is a lute that has a bulging belly and a sickle-shaped headstock. Part of that characterization comes from a c. 1330 poem, Libro de buen amor by Juan Ruiz, arcipestre de Hita, which described the "Moorish gittern" as "corpulent". The use of the adjective morisca tacked to guitarra may have been to differentiate it from the commonly seen Latin European variety, when the morisca was seen on a limited basis during the 14th century.

Elizabeth Drayson is Lorna Close Fellow in Spanish at Murray Edwards College, University of Cambridge. She is a specialist in medieval and early modern Spanish literature and cultural history. She produced the first translation and edition of Juan Ruiz's Libro de buen amor to appear in England.

The 1330s in music involved some events.