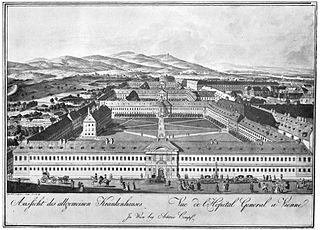

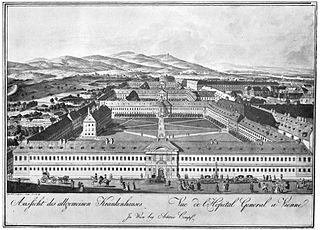

Ignaz Philipp Semmelweis was a Hungarian physician and scientist, who was an early pioneer of antiseptic procedures. Described as the "saviour of mothers", he discovered that the incidence of puerperal fever could be drastically reduced by requiring hand disinfection in obstetrical clinics. Puerperal fever was common in mid-19th-century hospitals and often fatal. He proposed the practice of washing hands with chlorinated lime solutions in 1847 while working in Vienna General Hospital's First Obstetrical Clinic, where doctors' wards had three times the mortality of midwives' wards. He published a book of his findings, Etiology, Concept and Prophylaxis of Childbed Fever (1861).

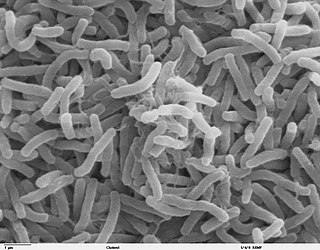

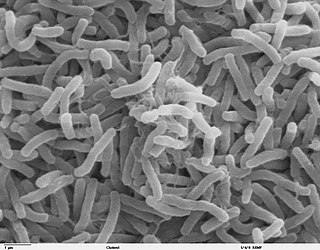

The germ theory of disease is the currently accepted scientific theory for many diseases. It states that microorganisms known as pathogens or "germs" can cause disease. These small organisms, too small to be seen without magnification, invade humans, other animals, and other living hosts. Their growth and reproduction within their hosts can cause disease. "Germ" refers to not just a bacterium but to any type of microorganism, such as protists or fungi, or even non-living pathogens that can cause disease, such as viruses, prions, or viroids. Diseases caused by pathogens are called infectious diseases. Even when a pathogen is the principal cause of a disease, environmental and hereditary factors often influence the severity of the disease, and whether a potential host individual becomes infected when exposed to the pathogen. Pathogens are disease-carrying agents that can pass from one individual to another, both in humans and animals. Infectious diseases are caused by biological agents such as pathogenic microorganisms as well as parasites.

Hand washing, also known as hand hygiene, is the act of cleaning one's hands with soap or handwash and water to remove viruses/bacteria/microorganisms, dirt, grease, or other harmful and unwanted substances stuck to the hands. Drying of the washed hands is part of the process as wet and moist hands are more easily recontaminated. If soap and water are unavailable, hand sanitizer that is at least 60% (v/v) alcohol in water can be used as long as hands are not visibly excessively dirty or greasy. Hand hygiene is central to preventing the spread of infectious diseases in home and everyday life settings.

A hospital-acquired infection, also known as a nosocomial infection, is an infection that is acquired in a hospital or other healthcare facility. To emphasize both hospital and nonhospital settings, it is sometimes instead called a healthcare-associated infection. Such an infection can be acquired in hospital, nursing home, rehabilitation facility, outpatient clinic, diagnostic laboratory or other clinical settings. A number of dynamic processes can bring contamination into operating rooms and other areas within nosocomial settings. Infection is spread to the susceptible patient in the clinical setting by various means. Healthcare staff also spread infection, in addition to contaminated equipment, bed linens, or air droplets. The infection can originate from the outside environment, another infected patient, staff that may be infected, or in some cases, the source of the infection cannot be determined. In some cases the microorganism originates from the patient's own skin microbiota, becoming opportunistic after surgery or other procedures that compromise the protective skin barrier. Though the patient may have contracted the infection from their own skin, the infection is still considered nosocomial since it develops in the health care setting. Nosocomial infection tends to lack evidence that it was present when the patient entered the healthcare setting, thus meaning it was acquired post-admission.

Postpartum infections, also known as childbed fever and puerperal fever, are any bacterial infections of the female reproductive tract following childbirth or miscarriage. Signs and symptoms usually include a fever greater than 38.0 °C (100.4 °F), chills, lower abdominal pain, and possibly bad-smelling vaginal discharge. It usually occurs after the first 24 hours and within the first ten days following delivery.

Semmelweis University is a research-led medical school in Budapest, Hungary, founded in 1769. With six faculties and a doctoral school it covers all aspects of medical and health sciences.

Ferdinand Karl Franz Schwarzmann, Ritter von Hebra was an Austrian Empire physician and dermatologist known as the founder of the New Vienna School of Dermatology, an important group of physicians who established the foundations of modern dermatology.

Asepsis is the state of being free from disease-causing micro-organisms. There are two categories of asepsis: medical and surgical. The modern day notion of asepsis is derived from the older antiseptic techniques, a shift initiated by different individuals in the 19th century who introduced practices such as the sterilizing of surgical tools and the wearing of surgical gloves during operations. The goal of asepsis is to eliminate infection, not to achieve sterility. Ideally, a surgical field is sterile, meaning it is free of all biological contaminants, not just those that can cause disease, putrefaction, or fermentation. Even in an aseptic state, a condition of sterile inflammation may develop. The term often refers to those practices used to promote or induce asepsis in an operative field of surgery or medicine to prevent infection.

Historically, puerperal fever was a devastating disease. It affected women within the first three days after childbirth and progressed rapidly, causing acute symptoms of severe abdominal pain, fever and debility.

Carl Edvard Marius Levy was professor and head of the Danish Maternity institution in Copenhagen. His name is sometimes spelled "Carl Eduard Marius Levy" or, in foreign literature, "Karl Edouard Marius Levy".

Johann Klein was professor of obstetrics at the University of Salzburg and at the University of Vienna. Johann Baptist Chiari was his son-in-law. In Vienna, he was succeeded by professor Carl Braun in 1856.

Carl Braun, sometimes Carl Rudolf Braun alternative spelling: Karl Braun, or Karl von Braun-Fernwald, name after knighthood Carl Ritter von Fernwald Braun was an Austrian obstetrician. He was born 22 March 1822 in Zistersdorf, Austria, son of the medical doctor Carl August Braun.

Professor August Breisky was an Austrian gynecologist and obstetrician.

Ignaz Semmelweis discovered in 1847 that hand-washing with a solution of chlorinated lime reduced the incidence of fatal childbed fever tenfold in maternity institutions. However, the reaction of his contemporaries was not positive; his subsequent mental disintegration led to him being confined to an insane asylum, where he died in 1865.

The Semmelweis reflex or "Semmelweis effect" is a metaphor for the reflex-like tendency to reject new evidence or new knowledge because it contradicts established norms, beliefs, or paradigms.

Joseph Hermann Schmidt was professor of obstetrics in Berlin, and official of the Prussian cultural ministry.

Carl Mayrhofer was a physician conducting work on the role of germs in childbed fever.

The Contagiousness of Puerperal Fever is an essay written by Oliver Wendell Holmes which first appeared in The New England Quarterly Journal of Medicine in 1843. It was later reprinted in the “Medical Essays” in 1855. It is included as Volume 38, Part 5 of the Harvard Classics series.

Alexander Gordon MA, MD was a Scottish obstetrician best known for clearly demonstrating the contagious nature of puerperal sepsis. By systematically recording details of all visits to women with the condition, he concluded that it was spread from patient to patient by the attending midwife or doctor, and he published these findings in his 1795 paper "Treatise on the Epidemic Puerperal Fever of Aberdeen". On the basis of these conclusions, he advised that the spread could be limited by fumigation of the clothing and burning of the bed linen used by women with the condition and by cleanliness of her medical and midwife attendants. He also recognised a connection between puerperal fever and erysipelas, a skin infection later shown to be caused by the bacterium Streptococcus pyogenes, the same organism that causes puerperal fever. His paper gave insights into the contagious nature of puerperal sepsis around half a century before the better-known publications of Ignaz Semmelweis and Oliver Wendell Holmes and some eighty years before the role of bacteria as infecting agents was clearly understood. Gordon's textbook The Practice of Physik gives valuable insights into medical practice in the later years of the Enlightenment. He advised that clinical decisions be based on personal observations and experience rather than ancient aphorisms.

In the mid to late nineteenth century, scientific patterns emerged which contradicted the widely held miasma theory of disease. These findings led medical science to what we now know as the germ theory of disease. The germ theory of disease proposes that invisible microorganisms are the cause of particular illnesses in both humans and animals. Prior to medicine becoming hard science, there were many philosophical theories about how disease originated and was transmitted. Though there were a few early thinkers that described the possibility of microorganisms, it was not until the mid to late nineteenth century when several noteworthy figures made discoveries which would provide more efficient practices and tools to prevent and treat illness. The mid-19th century figures set the foundation for change, while the late-19th century figures solidified the theory.