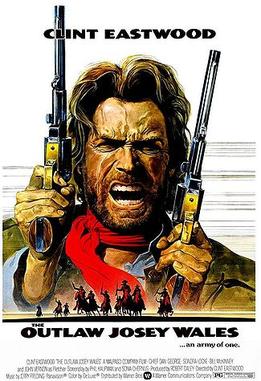

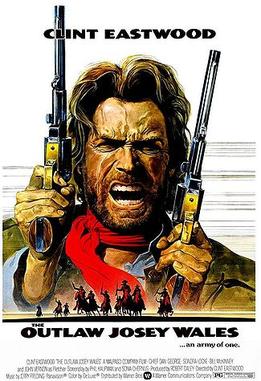

The Outlaw Josey Wales is a 1976 American revisionist Western film set during and after the American Civil War. It was directed by and starred Clint Eastwood, with Chief Dan George, Sondra Locke, Bill McKinney and John Vernon. The film tells the story of Josey Wales, a Missouri farmer whose family is murdered by Union militia during the Civil War. Driven to revenge, Wales joins a Confederate guerrilla band and makes a name for himself as a feared gunfighter. After the war, all the fighters in Wales' group except for him surrender to Union soldiers, but the Confederates end up being massacred. Wales becomes an outlaw and is pursued by bounty hunters and Union soldiers as he tries to make a new life for himself.

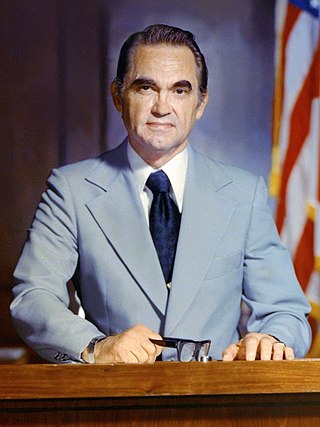

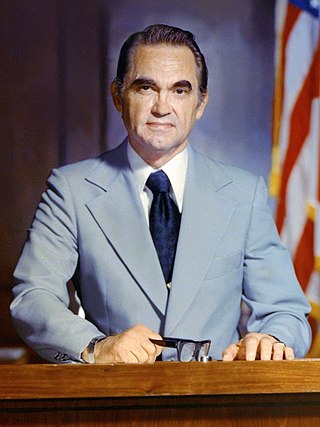

George Corley Wallace Jr. was an American politician and judge who served as the 45th governor of Alabama for four terms. He is remembered for his staunch segregationist and populist views. During Wallace's tenure as governor of Alabama, he promoted "industrial development, low taxes, and trade schools." Wallace sought the United States presidency as a Democratic Party candidate three times, and once as an American Independent Party candidate, being unsuccessful each time. Wallace opposed desegregation and supported the policies of "Jim Crow" during the Civil Rights Movement, declaring in his 1963 inaugural address that he stood for "segregation now, segregation tomorrow, segregation forever."

James Alexander Hood was one of the first African Americans to enroll at the University of Alabama in 1963, and was made famous when Alabama Governor George Wallace attempted to block him and fellow student Vivian Malone from enrolling at the then all-white university, an incident which became known as the "Stand in the Schoolhouse Door".

Jesse Benjamin Stoner Jr. was an American lawyer, white supremacist, neo-Nazi, segregationist politician, and domestic terrorist who perpetrated the 1958 bombing of the Bethel Baptist Church in Birmingham, Alabama, but was not convicted for the bombing of the church until 1980.

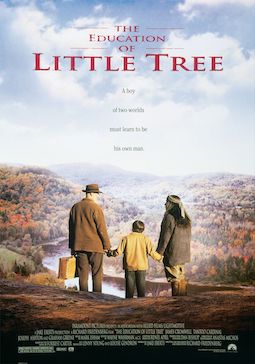

Asa Earl Carter was a 1950s segregationist political activist, Ku Klux Klan organizer, and later Western novelist. He co-wrote George Wallace's well-known pro-segregation line of 1963, "Segregation now, segregation tomorrow, segregation forever", and ran in the Democratic primary for governor of Alabama on a white supremacist ticket. Years later, under the pseudonym of supposedly Cherokee writer Forrest Carter, he wrote The Rebel Outlaw: Josey Wales (1972), a Western novel that led to a 1976 film featuring Clint Eastwood that was adopted into the National Film Registry, and The Education of Little Tree (1976), a best-selling, award-winning book which was marketed as a memoir but which turned out to be fiction.

John Malcolm Patterson was an American politician. He served one term as Attorney General of Alabama from 1955 to 1959, and, at age 37, served one term as the 44th Governor of Alabama from 1959 to 1963.

Vivian Juanita Malone Jones was one of the first two black students to enroll at the University of Alabama in 1963, and in 1965 became the university's first black graduate. She was made famous when George Wallace, the Governor of Alabama, attempted to block her and James Hood from enrolling at the all-white university.

Little tree or Little Trees may refer to:

Literary forgery is writing, such as a manuscript or a literary work, which is either deliberately misattributed to a historical or invented author, or is a purported memoir or other presumably nonfictional writing deceptively presented as true when, in fact, it presents untrue or imaginary information or content.

Following his election as governor of Alabama, George Wallace delivered an inaugural address on January 14, 1963 at the state capitol in Montgomery. At this time in his career, Wallace was an ardent segregationist, and as governor he challenged the attempts of the federal government to enforce laws prohibiting racial segregation in Alabama's public schools and other institutions. The speech is most infamous for the phrase "segregation now, segregation tomorrow, segregation forever", which became a rallying cry for those opposed to integration and the civil rights movement.

The Stand in the Schoolhouse Door took place at Foster Auditorium at the University of Alabama on June 11, 1963. George Wallace, the Governor of Alabama, in a symbolic attempt to keep his inaugural promise of "segregation now, segregation tomorrow, segregation forever" and stop the desegregation of schools, stood at the door of the auditorium as if to block the entry of two African American students: Vivian Malone and James Hood.

Dan T. Carter is an American historian.

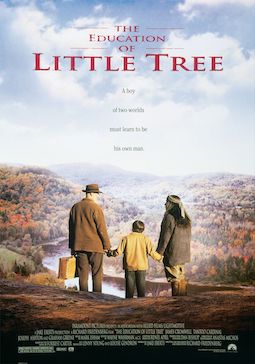

The Education of Little Tree is a 1997 American drama film written and directed by Richard Friedenberg, and starring James Cromwell, Tantoo Cardinal, Joseph Ashton and Graham Greene. It is based on the controversial 1976 fictional memoir of the same title by Asa Earl Carter about an orphaned boy raised by his paternal Scottish-descent grandfather and Cherokee grandmother in the Great Smoky Mountains.

The Rebel Outlaw: Josey Wales is a 1973 American Western novel written by Asa Earl Carter. It was adapted into the film The Outlaw Josey Wales directed by and starring Clint Eastwood. The novel was republished in 1975 under the title Gone to Texas.

The Return of Josey Wales is a 1986 American Western film directed by and starring Michael Parks It is a sequel to Clint Eastwood's 1976 film The Outlaw Josey Wales and was adapted from The Vengeance Trail of Josey Wales, the 1976 second novel featuring the Josey Wales character, by Asa Earl Carter. The novel was published under Carter's pen name, Forrest Carter, which he used to present a false persona involving a claim of Cherokee ancestry.

White America, Inc., was an organization founded in Pine Bluff, Arkansas, in February 1955. The organization was created following the desegregation of schools in Arkansas, to attempt to prevent "any attempts by Negroes to enter white schools" in the state. The group joined two other militant white supremacist organizations in September 1955 to attempt to intimidate the local school board of Hoxie to reverse its decision to integrate its schools.

Edward Reed Fields is an American white supremacist and anti-Semitic political activist.

The Anniston and Birmingham bus attacks, which occurred on May 14, 1961, in Anniston and Birmingham, both Alabama, were acts of mob violence targeted against civil rights activists protesting against racial segregation in the Southern United States. They were carried out by members of the Ku Klux Klan and the National States' Rights Party in coordination with the Birmingham Police Department. The FBI did nothing to prevent the attacks despite having foreknowledge of the plans.

The Reconstruction of Asa Carter is a 2011 American documentary film directed by Marco Ricci. It is about Asa Earl Carter (1925–1979), who was a segregationist activist in the Southern United States in the 1950s and 1960s, before he had mainstream success in the 1970s as the supposed Cherokee novelist Forrest Carter, which created a scandal when his real identity was revealed.