Philosophy of religion is "the philosophical examination of the central themes and concepts involved in religious traditions". Philosophical discussions on such topics date from ancient times, and appear in the earliest known texts concerning philosophy. The field is related to many other branches of philosophy, including metaphysics, epistemology, logic and ethics.

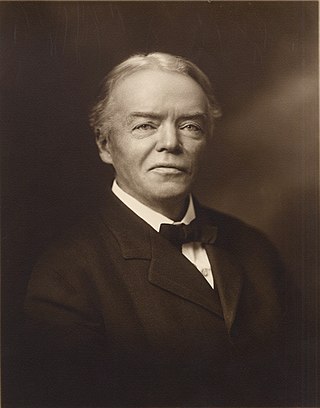

William James was an American philosopher and psychologist, and the first educator to offer a psychology course in the United States. James is considered to be a leading thinker of the late 19th century, one of the most influential philosophers of the United States, and the "Father of American psychology."

Pragmatism is a philosophical tradition that views language and thought as tools for prediction, problem solving, and action, rather than describing, representing, or mirroring reality. Pragmatists contend that most philosophical topics—such as the nature of knowledge, language, concepts, meaning, belief, and science—are all best viewed in terms of their practical uses and successes.

Richard McKay Rorty was an American philosopher. Educated at the University of Chicago and Yale University, he had strong interests and training in both the history of philosophy and in contemporary analytic philosophy. Rorty's academic career included appointments as the Stuart Professor of Philosophy at Princeton University, the Kenan Professor of Humanities at the University of Virginia, and as a professor of comparative literature at Stanford University. Among his most influential books are Philosophy and the Mirror of Nature (1979), Consequences of Pragmatism (1982), and Contingency, Irony, and Solidarity (1989).

Josiah Royce was an American Pragmatist and objective idealist philosopher and the founder of American idealism. His philosophical ideas included his joining of pragmatism and idealism, his philosophy of loyalty, and his defense of absolutism.

Arthur Oncken Lovejoy was an American philosopher and intellectual historian, who founded the discipline known as the history of ideas with his book The Great Chain of Being (1936), on the topic of that name, which is regarded as 'probably the single most influential work in the history of ideas in the United States during the last half century'. He was elected to the American Philosophical Society in 1932. In 1940, he founded the Journal of the History of Ideas.

A pragmatic theory of truth is a theory of truth within the philosophies of pragmatism and pragmaticism. Pragmatic theories of truth were first posited by Charles Sanders Peirce, William James, and John Dewey. The common features of these theories are a reliance on the pragmatic maxim as a means of clarifying the meanings of difficult concepts such as truth; and an emphasis on the fact that belief, certainty, knowledge, or truth is the result of an inquiry.

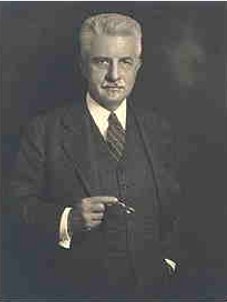

William Ernest Hocking was an American idealist philosopher at Harvard University. He continued the work of his philosophical teacher Josiah Royce in revising idealism to integrate and fit into empiricism, naturalism and pragmatism. He said that metaphysics has to make inductions from experience: "That which does not work is not true." His major field of study was the philosophy of religion, but his 22 books included discussions of philosophy and human rights, world politics, freedom of the press, the philosophical psychology of human nature; education; and more. In 1958 he served as president of the Metaphysical Society of America. He led a highly influential study of missions in mainline Protestant churches in 1932. His "Laymen's Inquiry" recommended a greater emphasis on education and social welfare, transfer of power to local groups, less reliance on evangelizing and conversion, and a much more respectful appreciation for local religions.

Neopragmatism, sometimes called post-Deweyan pragmatism, linguistic pragmatism, or analytic pragmatism, is the philosophical tradition that infers that the meaning of words is a result of how they are used, rather than the objects they represent.

Scholarly approaches to mysticism include typologies of mysticism and the explanation of mystical states. Since the 19th century, mystical experience has evolved as a distinctive concept. It is closely related to "mysticism" but lays sole emphasis on the experiential aspect, be it spontaneous or induced by human behavior, whereas mysticism encompasses a broad range of practices aiming at a transformation of the person, not just inducing mystical experiences.

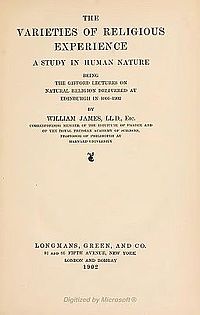

Overbelief is a philosophical term for a belief adopted that requires more evidence than one presently has. It is also described as a kind of metaphysical belief ascribed with the status of speculative view that exceeds available evidence or evidencing reason. Generally, acts of overbelief are justified on emotional need or faith, and a need to make sense of spiritual experience, rather than on empirical evidence. This idea originates from the works of William James in The Varieties of Religious Experience and refers to the conceptual framework that individuals have.

Walter Terence Stace was a British civil servant, educator, public philosopher and epistemologist, who wrote on Hegel, mysticism, and moral relativism. He worked with the Ceylon Civil Service from 1910 to 1932, and from 1932 to 1955 he was employed by Princeton University in the Department of Philosophy. He is most renowned for his work in the philosophy of mysticism, and for books like Mysticism and Philosophy (1960) and Teachings of the Mystics (1960). These works have been influential in the study of mysticism, but they have also been severely criticised for their lack of methodological rigor and their perennialist pre-assumptions.

Cosmic Consciousness: A Study in the Evolution of the Human Mind is a 1901 book by the psychiatrist Richard Maurice Bucke, in which the author explores the concept of cosmic consciousness, which he defines as "a higher form of consciousness than that possessed by the ordinary man".

Richard Shusterman is an American pragmatist philosopher. Known for his contributions to philosophical aesthetics and the emerging field of somaesthetics, currently he is the Dorothy F. Schmidt Eminent Scholar in the Humanities and Professor of Philosophy at Florida Atlantic University.

In the philosophy of religion and theology, post-monotheism is a term covering a range of different meanings that nonetheless share concern for the status of faith and religious experience in the modern or post-modern era. There is no one originator for the term. Rather, it has independently appeared in the writings of several intellectuals on the Internet and in print. Its most notable use has been in the poetry of Arab Israeli author Nidaa Khoury, and as a label for a "new sensibility" or theological approach proposed by the Islamic historian Christopher Schwartz.

Richard Jacob Bernstein was an American philosopher who taught for many years at Haverford College and then at The New School for Social Research, where he was Vera List Professor of Philosophy. Bernstein wrote extensively about a broad array of issues and philosophical traditions including American pragmatism, neopragmatism, critical theory, deconstruction, social philosophy, political philosophy, and hermeneutics.

American philosophy is the activity, corpus, and tradition of philosophers affiliated with the United States. The Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy notes that while it lacks a "core of defining features, American Philosophy can nevertheless be seen as both reflecting and shaping collective American identity over the history of the nation". The philosophy of the Founding Fathers of the United States is largely seen as an extension of the European Enlightenment. A small number of philosophies are known as American in origin, namely pragmatism and transcendentalism, with their most prominent proponents being the philosophers William James and Ralph Waldo Emerson respectively.

Ralph Wilbur Hood Jr. is an American psychologist. He serves as Leroy A. Martin Distinguished Professor of Religious Studies at the University of Tennessee at Chattanooga, where he specializes in the psychology of religion.

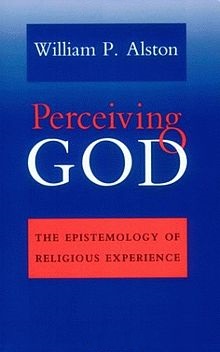

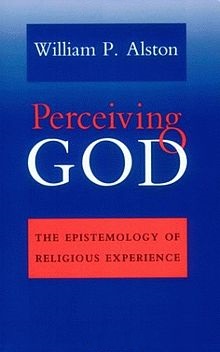

Perceiving God: The Epistemology of Religious Experience is a 1991 book about the philosophy of religion by the philosopher William Alston, in which the author discusses experiential awareness of God. The book was first published in the United States by Cornell University Press. The book received positive reviews and has been described as an important, well-argued, and seminal work. However, Alston was criticized for his treatment of the conflict between the competing claims made by different religions.

Ronald A. Kuipers is a Canadian philosopher of religion based in Toronto, Ontario.