Related Research Articles

The French Republican calendar, also commonly called the French Revolutionary calendar, was a calendar created and implemented during the French Revolution, and used by the French government for about 12 years from late 1793 to 1805, and for 18 days by the Paris Commune in 1871, and meant to replace the Gregorian calendar.

The Julian calendar is a solar calendar of 365 days in every year with an additional leap day every fourth year. The Julian calendar is still used as a religious calendar in parts of the Eastern Orthodox Church and in parts of Oriental Orthodoxy as well as by the Amazigh people.

A leap year is a calendar year that contains an additional day compared to a common year. The 366th day is added to keep the calendar year synchronised with the astronomical year or seasonal year. Since astronomical events and seasons do not repeat in a whole number of days, calendars having a constant number of days each year will unavoidably drift over time with respect to the event that the year is supposed to track, such as seasons. By inserting ("intercalating") an additional day—a leap day—or month—a leap month—into some years, the drift between a civilization's dating system and the physical properties of the Solar System can be corrected.

A month is a unit of time, used with calendars, that is approximately as long as a natural orbital period of the Moon; the words month and Moon are cognates. The traditional concept of months arose with the cycle of Moon phases; such lunar months ("lunations") are synodic months and last approximately 29.53 days, making for roughly 12.37 such months in one Earth year. From excavated tally sticks, researchers have deduced that people counted days in relation to the Moon's phases as early as the Paleolithic age. Synodic months, based on the Moon's orbital period with respect to the Earth–Sun line, are still the basis of many calendars today and are used to divide the year.

The Roman calendar was the calendar used by the Roman Kingdom and Roman Republic. Although the term is primarily used for Rome's pre-Julian calendars, it is often used inclusively of the Julian calendar established by the reforms of the Dictator Julius Caesar and Emperor Augustus in the late 1st century BC.

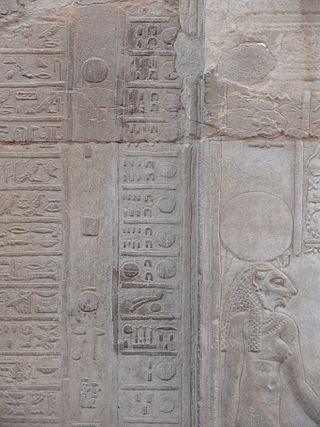

The ancient Egyptian calendar – a civil calendar – was a solar calendar with a 365-day year. The year consisted of three seasons of 120 days each, plus an intercalary month of five epagomenal days treated as outside of the year proper. Each season was divided into four months of 30 days. These twelve months were initially numbered within each season but came to also be known by the names of their principal festivals. Each month was divided into three 10-day periods known as decans or decades. It has been suggested that during the Nineteenth Dynasty and the Twentieth Dynasty the last two days of each decan were usually treated as a kind of weekend for the royal craftsmen, with royal artisans free from work.

As a moveable feast, the date of Easter is determined in each year through a calculation known as computus. Easter is celebrated on the first Sunday after the Paschal full moon. Determining this date in advance requires a correlation between the lunar months and the solar year, while also accounting for the month, date, and weekday of the Julian or Gregorian calendar. The complexity of the algorithm arises because of the desire to associate the date of Easter with the date of the Jewish feast of Passover which, Christians believe, is when Jesus was crucified.

A perpetual calendar is a calendar valid for many years, usually designed to look up the day of the week for a given date in the past or future.

Piphilology comprises the creation and use of mnemonic techniques to remember many digits of the mathematical constant π. The word is a play on the word "pi" itself and of the linguistic field of philology.

A metrical psalter is a kind of Bible translation: a book containing a verse translation of all or part of the Book of Psalms in vernacular poetry, meant to be sung as hymns in a church. Some metrical psalters include melodies or harmonisations. The composition of metrical psalters was a large enterprise of the Protestant Reformation, especially in its Calvinist manifestation.

Chidiock Tichborne, erroneously referred to as Charles, was an English conspirator and poet.

Henry Constable was an English poet, known particularly for Diana, one of the first English sonnet sequences. In 1591 he converted to Catholicism, and lived in exile on the continent for some years. He returned to England at the accession of King James, but was soon a prisoner in the Tower and in the Fleet. He died an exile at Liège in 1613.

Mercedonius, also known as Mercedinus, Interkalaris or Intercalaris, was the intercalary month of the Roman calendar. The resulting leap year was either 377 or 378 days long. It theoretically occurred every two years, but was sometimes avoided or employed by the Roman pontiffs for political reasons regardless of the state of the solar year. Mercedonius was eliminated by Julius Caesar when he introduced the Julian calendar in 45 BC.

Richard Grafton was King's Printer under Henry VIII and Edward VI. He was a member of the Grocers' Company and MP for Coventry elected 1562/63.

The Buddhist calendar is a set of lunisolar calendars primarily used in Tibet, Cambodia, Laos, Myanmar, Bangladesh, India, Sri Lanka, Thailand and Vietnam as well as in Malaysia and Singapore and by Chinese populations for religious or official occasions. While the calendars share a common lineage, they also have minor but important variations such as intercalation schedules, month names and numbering, use of cycles, etc. In Thailand, the name Buddhist Era is a year numbering system shared by the traditional Thai lunar calendar and by the Thai solar calendar.

The intercalary month or epagomenal days of the ancient Egyptian, Coptic, and Ethiopian calendars are a period of five days in common years and six days in leap years in addition to those calendars' 12 standard months, sometimes reckoned as their thirteenth month. They originated as a periodic measure to ensure that the heliacal rising of Sirius would occur in the 12th month of the Egyptian lunar calendar but became a regular feature of the civil calendar and its descendants. Coptic and Ethiopian leap days occur in the year preceding Julian and Gregorian leap years.

A menologium, also known by other names, is any collection of information arranged according to the days of a month, usually a set of such collections for all the months of the year. In particular, it is used for ancient Roman farmers' almanacs ; for the untitled Old English poem on the Julian calendar that appears in a manuscript of the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle; for the liturgical books used by the Eastern Orthodox Church and Eastern Catholic Churches following the Byzantine Rite that list the propers for fixed dates, typically in twelve volumes covering a month each and largely concerned with saints; for hagiographies and liturgical calendars written as part of this tradition; and for equivalents of these works among Roman Catholic religious orders for organized but private commemoration of their notable members.

Maius or mensis Maius (May) was the third month of the ancient Roman calendar, following Aprilis (April) and preceding Iunius (June). On the oldest Roman calendar that had begun with March, it was the third of ten months in the year. May had 31 days.

The Gregorian calendar is the calendar used in most parts of the world. It went into effect in October 1582 following the papal bull Inter gravissimas issued by Pope Gregory XIII, which introduced it as a modification of, and replacement for, the Julian calendar. The principal change was to space leap years differently so as to make the average calendar year 365.2425 days long, more closely approximating the 365.2422-day 'tropical' or 'solar' year that is determined by the Earth's revolution around the Sun.

The Hanke–Henry Permanent Calendar (HHPC) is a proposal for calendar reform. It is one of many examples of leap week calendars, calendars that maintain synchronization with the solar year by intercalating entire weeks rather than single days. It is a modification of a previous proposal, Common-Civil-Calendar-and-Time (CCC&T). With the Hanke–Henry Permanent Calendar, every calendar date always falls on the same day of the week. A major feature of the calendar system is the abolition of time zones.

References

- 1 2 3 "How Old is 'Thirty Days Has September...'", Blog, Dictionary.com, 18 January 2012.

- 1 2 Mommsen (1894) , Vol. I, Ch. xiv.

- ↑ Mommsen (1894) , Vol. V, Ch. xi.

- ↑ Rüpke (2011), p. 112.

- ↑ Rüpke (2011), p. 113.

- 1 2 3 Ballew, Pat (1 September 2015), "On This Day in Math", Pat's Blog .

- 1 2 Anianus, Computus Metricus Manualis, Strasbourg. (in Latin)

- 1 2 Misstear, Rachael (16 January 2012), "Welsh Author Digs Deep to Find Medieval Origins of Thirty Days Hath Verse", Wales Online, Media Wales.

- ↑ Bryan (2011).

- 1 2 3 4 5 Bryan, Roger (30 October 2011), "The Oldest Rhyme in the Book", The Times, London: Times Newspapers.

- ↑ "Memorable Mnemonics", Today, London: BBC Radio 4, 30 November 2011.

- ↑ Cryer (2010), "Thirty Days Has September".

- 1 2 Grafton (1562).

- 1 2 3 4 Holland (1992) , p. 64–5.

- ↑ Ganvoort, A.J. (August 1891), "Value of Music in Public Education", The Ohio Educational Monthly and the National Teacher, Vol. XL, No. 8, p. 392 .

- ↑ Stevins MS.

- ↑ OCDQ (2006), p. 45.

- ↑ Comly, John, Spelling Book, Philadelphia: Kimber & Sharpless, 1827, https://books.google.com/books?id=nWwBAAAAYAAJ&q=%22September,+.+April,+June,+and+November,+All+the+rest+have+thirty-one,+Excepting+February%22&pg=PP6

- ↑ Fowle, William B., The Child's Arithmetic, Or, The Elements of Calculation, in the Spirit of Pestalozzi's Method, for the Use of Children Between the Ages of Three and Seven Years, Boston: Wm. B. Fowle & N. Capen, 1844, https://books.google.com/books?id=8uT8GxU0FUMC&q=editions:UOM35112103818284

- 1 2 3 Onofri, Francesca Romana; et al. (2012), Italian for Dummies, Berlitz, pp. 101–2, ISBN 9781118258767 .

- ↑ Anon. (1606) , Act III, sc. i.

- ↑ Smeaton (1905) , p. xxvi.

- ↑ The Cincinnati Enquirer, Cincinnati, 20 September 1924, p. 6

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link). - ↑ "Thirty Days", Jingles, Burma-Shave.org, 2005.

Bibliography

- Anon. (1905), Smeaton, Oliphant (ed.), The Return from Parnassus, London: J.M. Dent & Co., a reprint of the 1606 The Returne from Pernassus, or, The Scourge of Simony, The Tudor facsimile texts, Issued for subscribers by the editor of the Tudor facsimile texts, 1912.

- Bryan, Roger (2011), It'll Come In Useful One Day, Llanina Books.

- Cryer, Max (2010), Common Phrases... and the Amazing Stories Behind Them, New York: Skyhorse Publishing, ISBN 9781616081430 .

- Grafton, Richard (1562), Abridgement of the Chronicles of Englande, London: Richard Tottell.

- Holland, Norman N. (1992), The Critical I, New York: Columbia University Press, ISBN 9780231076517 .

- Ratcliffe, Susan, ed. (2006), Oxford Concise Dictionary of Quotations, 5th ed., Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0-19-861417-3 .

- Rüpke, Jörg (2011), Richardson, David M.B. (ed.), The Roman Calendar from Numa to Constantine: Time, History, and the Fasti, Malden: Wiley-Blackwell, ISBN 9781444396522 , a translation of the 1995 Kalendar und Öffentlichkeit.

- Mommsen, Theodor (1894), Dickson, William Purdie (ed.), The History of Rome , a translation of the 1861 &c. Romische Geschichte.