Bridgewater or Bridgwater may refer to:

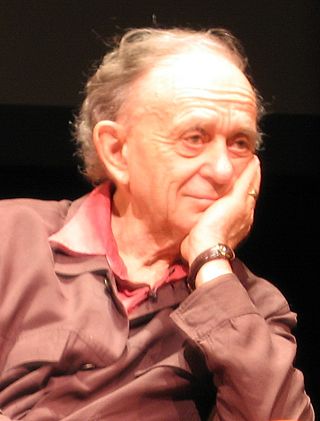

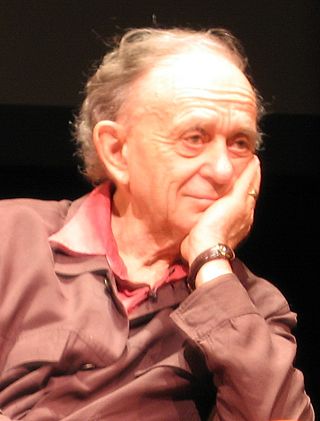

High School is a 1968 American documentary film by Frederick Wiseman that shows a typical day for students and faculty at a Pennsylvanian high school during the late 1960s. It is one of the first direct cinema documentaries. It was shot over five weeks between March and April 1968 at Northeast High School in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. The film was not shown in Philadelphia at the time of its release, because of Wiseman's concerns over what he called "vague talk" of a lawsuit.

Hospital is an 84-minute 1970 American documentary film directed by Frederick Wiseman, which explores the daily activities of the people at Metropolitan Hospital Center, a large-city hospital in New York City, with emphasis on its emergency ward and outpatient clinics.

Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center (BIDMC) in Boston, Massachusetts is a teaching hospital of Harvard Medical School. It was formed out of the 1996 merger of Beth Israel Hospital and New England Deaconess Hospital. Among independent teaching hospitals, Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center consistently ranks in the top three recipients of biomedical research funding from the National Institutes of Health. Research funding totals nearly $200 million annually. BIDMC researchers run more than 850 active sponsored projects and 200 clinical trials. The Harvard-Thorndike General Clinical Research Center, the oldest clinical research laboratory in the United States, has been located on this site since 1973.

Frederick Wiseman is an American filmmaker, documentarian, and theater director. His work is "devoted primarily to exploring American institutions". He has been called "one of the most important and original filmmakers working today".

Tewksbury Hospital is a National Register of Historic Places-listed site located on an 800+ acre campus in Tewksbury, Massachusetts. The centerpiece of the hospital campus is the 1894 Richard Morris Building.

James Draper St. Clair was an American lawyer, who practiced law for many years in Boston with the firm of Hale & Dorr. He was the chief legal counsel for President Richard Nixon during the Watergate scandal.

Powick Hospital, which opened in 1847 was a psychiatric facility located on 552 acres (223 ha) outside the village of Powick, near Malvern, Worcestershire. At its peak, the hospital housed around 1,000 patients in buildings designed for 400. During the 1950s the hospital gained an internationally acclaimed reputation for its use of the drug LSD in psychotherapy pioneered and conducted by Ronald A. Sandison. In 1968 the institution was surrounded by controversy concerning serious neglect of patients. In 1989 it was closed down leaving Barnsley Hall Hospital in Bromsgrove as the remaining psychiatric hospital in the county. Most of the complex has been demolished to make way for a housing estate.

The Massachusetts Department of Correction is the government agency responsible for operating the prison system of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts in the United States. The Massachusetts Department of Correction is responsible for the custody of about 8,292 prisoners throughout 16 correctional facilities and is the 5th largest state agency in the state of Massachusetts, employing over 4,800 people. The Massachusetts Department of Correction also has a fugitive apprehension unit, a gang intelligence unit, a K9 Unit, a Special Reaction Team (SRT), and a Tactical Response Team (TRT). Both of these tactical units are highly trained and are paramilitary in nature. The agency is headquartered in Milford, Massachusetts and currently headed by Commissioner Carol Mici.

Superintendent v. Hill, 472 U.S. 445 (1985), was a United States Supreme Court case in which the Court held that due process required that prison disciplinary decisions to revoke good-time credits must be supported by "some evidence."

John Kennedy Marshall was an American anthropologist and acclaimed documentary filmmaker best known for his work in Namibia recording the lives of the Juǀʼhoansi.

Northampton State Hospital was a historic psychiatric hospital at 1 Prince Street on top of Hospital Hill outside of Northampton, Massachusetts. The hospital building was constructed in 1856. It operated until 1993, and the building was added to the National Register of Historic Places in 1994.

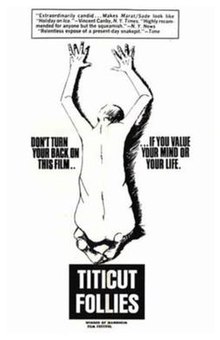

Bridgewater State Hospital, located in southeastern Massachusetts, is a state facility housing the criminally insane and those whose sanity is being evaluated for the criminal justice system. It was established in 1855 as an almshouse. It was then used as a workhouse for inmates with short sentences who worked the surrounding farmland. It was later rebuilt in the 1880s and again in 1974. As of January 6, 2020 there were 217 inmates in general population beds. The facility was the subject of the 1967 documentary Titicut Follies. Bridgewater State Hospital falls under the jurisdiction of the Massachusetts Department of Correction but its day to day operations is managed by Wellpath, a contracted vendor.

Old Colony Correctional Center is a Massachusetts Department of Correction men's prison in Bridgewater, Massachusetts. The medium security facility is located in a 30-acre (12 ha) plot of land in the Bridgewater Correctional Complex with the Bridgewater State Hospital and the Massachusetts Treatment Center. Old Colony Correctional Center Minimum Unit is under the authority of the correctional center. As of January 6, 2020 there were 553 medium and 106 minimum inmates in general population beds.

Metropolitan Hospital Center is a hospital in East Harlem, New York City. It has been affiliated with New York Medical College since it was founded in 1875, representing the oldest partnership between a hospital and a private medical school in the United States.

The Alabama Institute for Deaf and Blind (AIDB) is the world’s most comprehensive education, rehabilitation and service program serving individuals of all ages who are deaf, blind, deafblind and multidisabled. It is operated by the U.S. state of Alabama in the city of Talladega. The current institution includes the Alabama School for the Deaf, the Alabama School for the Blind, and the Helen Keller School of Alabama, named for Alabamian Helen Keller, which serves children who are both deaf and blind. E. H. Gentry Facility provides vocational training for adult students, and the institution offers employment through its Alabama Industries for the Blind facilities in Talladega and Birmingham. AIDB has regional centers in Birmingham, Decatur, Dothan, Huntsville, Mobile, Montgomery, Opelika, Shoals, Talladega, and Tuscaloosa. AIDB currently serves over 36,000 residents from all 67 counties of the state.

Law and Order is a 1969 documentary film by Frederick Wiseman that shows the daily routine of officers of the Kansas City Police Department. It was Wiseman's third film after Titicut Follies (1967) and High School (1968). The films were among the earliest examples of direct cinema by a U.S. filmmaker.

Boxing Gym is a 2010 American documentary film edited, produced, and directed by Frederick Wiseman. The film premiered at the 63rd Cannes Film Festival on May 20, 2010.

Hudson v. Palmer, 468 U.S. 517 (1984), is a United States Supreme Court case in which the Court held that prison inmates have no privacy rights in their cells protected by the Fourth Amendment to the United States Constitution. The Court also held that an intentional deprivation of property by a state employee "does not violate the Fourteenth Amendment if an adequate postdeprivation state remedy exists," extending Parratt v. Taylor to intentional torts.

City Hall is a 2020 American documentary film directed, edited, and co-produced by Frederick Wiseman. It explores the government of Boston, Massachusetts.